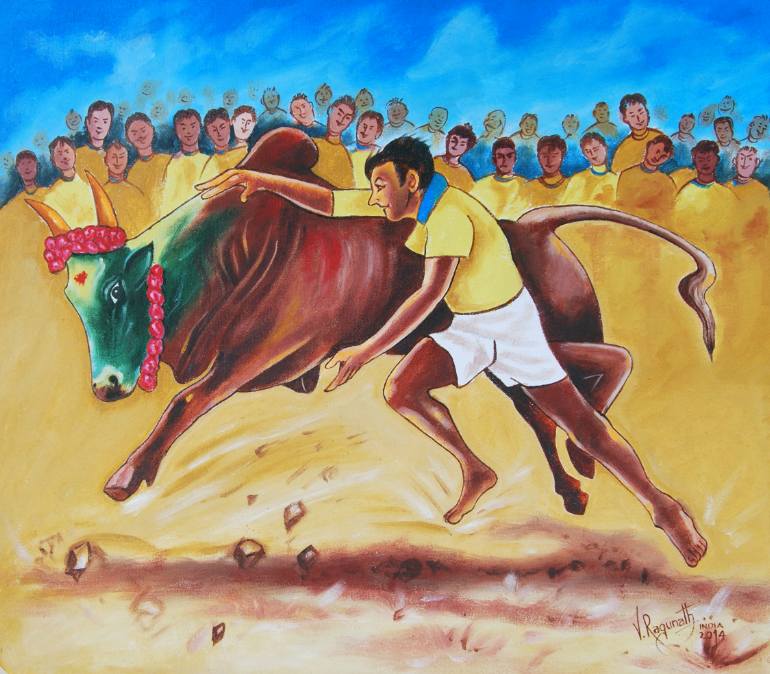

Jallikattu, also known as Eru Thazhuvuthal and Mañcuvirattu, is a traditional event during the Pongal festival in which a bull, of the Pulikulam or Kangayam breeds, is released into a crowd of people, and multiple human participants attempt to grab the large hump on the bull’s back with both arms and hang on to it while the bull attempts to escape. Participants hold the hump for as long as possible, attempting to bring the bull to a stop. In some cases, participants must ride long enough to remove flags on the bull’s horns. Jallikattu is typically practised in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu as a part of Pongal celebrations on Mattu Pongal day, which occurs annually in January. The most popular Jallikattu is the one celebrated at Alanganallur near Madurai.

Ancient Tamil Sangams described the practice as yeru thazhuvuthal or bull embracing. The modern term jallikattu or sallikattu is derived from salli or coins and kattu or package, which refers to a prize of coins that are tied to the bull’s horns and that participants attempt to retrieve. Mancu virattu means bull chasing.

Jallikattu has been known to be practised during the Tamil classical period between 400 and 100 BC. It was common among the Ayar people who lived in the Mullai geographical division of the ancient Tamizh Nadu. Later, it became a platform for the display of bravery, and the prize money was introduced for participation encouragement. A seal from the Indus Valley civilization depicting the practice is preserved in the National Museum in New Delhi. A cave painting in white kaolin discovered near Madurai depicting a lone man trying to control a bull is estimated to be about 1,500 years old.

The popular myth revolving around this festival is about how Lord Shiva asked Basava, his bull, to convey two messages. This bull twisted the words of the messages and expressed them in another way. It is said that the bull was asked to tell the human beings on earth to take an oil bath every day and that food must be consumed only once a month for six months. Instead of this message, the bull conveyed that food must be consumed daily and oil baths must be taken only once a month. This debacle made Lord Shiva angry and he cursed the bull to aid humans in cultivating their land for all eternity.

Some variants of Jallikattu include the Vadi Manjuviratttu, the most common category of Jallikattu. Here, the bull is released from a closed space or Vadi vasal and the contestants attempt to wrap their arms or hands around the hump of the bull and hold on to it to win the award. Only one person is allowed to attempt at a time. This variant is most common in the districts of Madurai, Theni, Thanjavur, and Salem. In Veli Virattu, the approach is slightly different as the bull is directly released into open ground. The rules are the same as that of Vadi Majuvirattu and this is a popular variant in the districts of Sivagangai and Madurai. In the Vatam Manjuvirattu, the bull is tied with a 15 m rope where a vatam means a circle in Tamil. There are no other physical restrictions for the bull and hence it can move freely anywhere. The maximum time given is 30 minutes and a team of seven to nine members can attempt to untie the gift token that is tied to the bull’s horn.

Bulls enter the competition area through a gate called the vadi vasal. Typically, participants must only hold onto the bull’s hump. In some variations, they are disqualified if they hold onto the bull’s neck, horns or tail. There may be several goals to the game depending on the region. In some versions, contestants must either hold the bull’s hump for 30 seconds or 15 m. If the contestant is thrown by the bull or falls, they lose. Some variations only allow for one contestant. If two people grab the hump, then neither person wins. Bulls for Jallikatu are bred specifically and bulls that participate successfully in jallikattu are used as studs for breeding and also fetch higher prices in the markets.

With the introduction of the Regulation of Jallikattu Act, 2009, by the Tamil Nadu legislature, before the event, a written permission is obtained from the respective collectors, thirty days before the event along with the notification of the event location. The arena and the way through which the bulls pass are double-barricaded, to avoid injuries to spectators and bystanders who may be permitted to remain within the barricades. The gallery areas are built up along the double barricades and necessary permissions are obtained from the collector for the participants and the bulls fifteen days prior. Final preparations before the event includes complete testing by the authorities of the Animal Husbandry Department, to ensure that performance-enhancement drugs, liquor or other irritants are not used on the bulls.

Incidents of injury and death associated with the sport, both to participants and animals forced into it, animal rights organisations have called for a ban on the sport, resulting in the court banning it several times over the past years. However, with protests from the people against the ban, a new ordinance was made in 2017 to continue the sport.

Between 2008 and 2020, more than 70 people died and about 10 4 bulls were killed in Jallikattu events. Animal welfare concerns are related to the handling of the bulls before they are released and also during competitors’ attempts to subdue the bull. Practices, before the bull is released, include prodding the bull with sharp sticks or scythes, extreme bending of the tail which can fracture the vertebrae, and biting the bull’s tail. There are also reports of the bulls being forced to drink alcohol to disorient them, or chilli peppers being rubbed in their eyes to aggravate the bull. During attempts to subdue the bull, they are stabbed by various implements such as knives or sticks, punched, jumped on and dragged to the ground. In variants in which the bull is not enclosed, they may run into traffic or other dangerous places, sometimes resulting in broken bones or death. Protestors claim that Jallikattu is promoted as bull taming, however, others suggest it exploits the bull’s natural nervousness by deliberately placing them in a terrifying situation in which they are forced to run away from the competitors which they perceive as predators and the practice effectively involves catching a terrified animal. Along with human injuries and fatalities, bulls themselves sometimes sustain injuries or die, which people may interpret as a bad omen for the village.

Animal welfare organisations such as the Federation of Indian Animal Protection Organisations or FIAPO and PETA India have protested against the practice. The former Indian Minister of Women and Child Development, Maneka Gandhi denied the claim by Jallikattu aficionados that the sport is only to demonstrate the Tamil love for the bull, citing that the Tirukkural does not sanction cruelty to animals.

The Jallikattu Premier League is a professional league in Tamil Nadu for Jallikattu. The league was announced on 24 February 2018, to be organised in Chennai by the Tamil Nadu Jallikattu Peravai and the Chennai Jallikattu Amaippu. Kabaddi is usually played as a warm-up sport before the players enter the arena for Jallikattu.