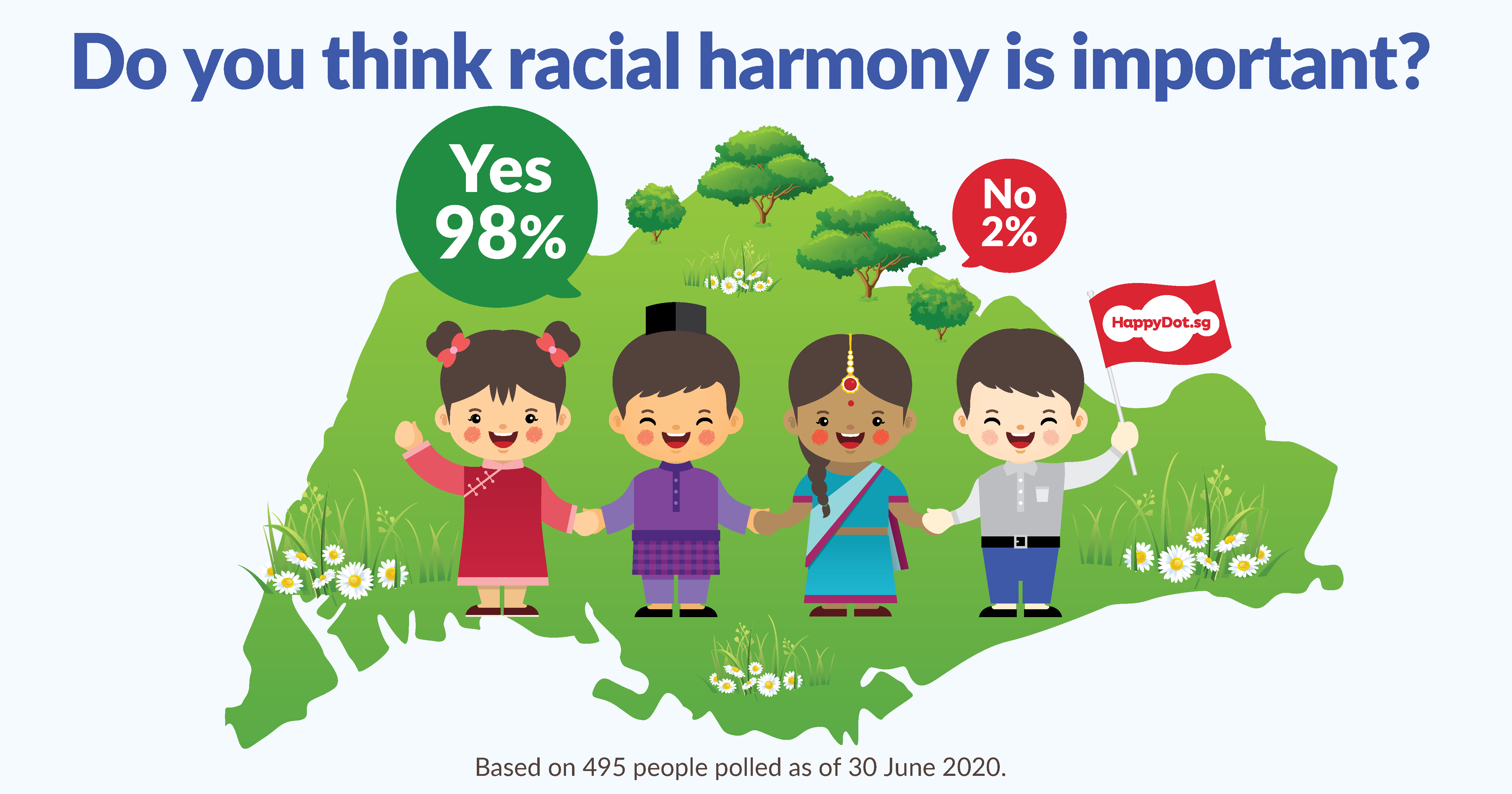

Today in Singapore, we celebrate Racial Harmony Day. The day is celebrated to commemorate the country’s success as a racially harmonious nation and is mostly celebrated in schools and other educational institutions. First launched in 1997 by the Ministry of Education in schools, the event commemorates the 1964 race riots which took place on 21 July 1964 when Singapore was still part of Malaysia, in which 22 people lost their lives and hundreds were severely injured. There were numerous other communal riots and incidents throughout the 50s and 60s leading to and after Singapore’s independence in August 1965.

On this day, students in schools across the nation are encouraged to be dressed in other cultures’ traditional costumes such as the Cheongsam, the Baju Kurung and the Saree. Traditional delicacies are a feature of the celebration with traditional games such as five stones, zero points, and hopscotch played and students are encouraged to try out foods from other cultures. Schools are also encouraged to recite a Declaration of Religious Harmony during the celebrations. During this week, representatives from the Inter-Religious Harmony Circle or IRHC comprising various religious groups also get together to pledge their support and to promote the Declaration.

The 1964 race riots in Singapore involved a series of communal race-based civil disturbances between the Malays and Chinese in Singapore following its merger with Malaysia in 1963 and were considered to be the worst and most prolonged in Singapore’s postwar history. The term is also used to refer specifically to two riots on 21 July 1964 and 2 September 1964, particularly the former, during which 23 people died and 454 others suffered severe injuries. The riots are seen as pivotal in leading up to the independence of Singapore in 1965, its policies of multiracialism and multiculturalism, and justifying laws such as the Internal Security Act.

This riot occurred during the procession to celebrate Mawlid, the birthday of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. 25,000 Muslim Malay people had gathered at the Padang. Aside from the recital of some prayers and engagement in some religious activities, a series of fiery speeches were also made by the organisers, instigating racial tensions. During the procession, clashes occurred between the Malays and the Chinese which eventually led to a riot spreading to other areas. There are multiple accounts and reports on how the riots began. The dominant narration of the July 1964 Racial riot on public forums and history textbooks is simplified and remembered as a riot that involved 20,000 Chinese throwing bottles and rocks at the Malays at the Padang. In reality, some scholars argue that the bottles and rocks being thrown and the clash with a Malay policeman who tried to restrain the Malays were not the reasons for the cause of the riots. But rather, part of the reasons could be also attributed to the distribution of leaflets to the Malay community before the start of the procession by a group named Pertobohan Perjuangan Kebangsaan Melayu Singapore.

The official Malaysian state narrative on the cause of 21 July 1964 characterises the UMNO and Malay-language newspaper Utusan Melayu controlled by UMNO as playing an instigating role. It points to the publishing of anti-PAP headlines and incitement of the Malays against the PAP. To address the grievances of the Malays, PM Lee Kwan Yew held a meeting with various Malay organisations on 19 July. This angered UMNO, as it was not invited to attend this meeting. In that meeting, Lee assured the Malays that they would be given ample opportunities in education, employment and skill training for them to compete effectively with the non-Malays in the country. However, PM Lee refused to promise the granting of special rights to the Malays. This meeting satisfied some Malay community leaders and agitated some, who had the view that the needs and pleas of the Malays were not being heard. To rally the support of the Malays to go against the PAP government, leaflets containing rumours of the Chinese in Singapore trying to kill the Malays were published and distributed throughout the island on 20 July 1964. The spread of such information was also carried out during the procession of Muhammad’s birthday celebration, triggering the riots.

From the Malaysian government’s point of view, Lee Kuan Yew and the PAP were responsible for instigating the series of riots and discontent among the Malay community in Singapore. UMNO and Tun Razak had attributed to the Malay’s anger and hostility towards the Chinese and Lee Kuan Yew’s former speech made on 30 June 1964 for passing inflammatory remarks of the UMNO’s communal politics. Whereas the PAP and Lee Kuan Yew strongly believed that the 1964 July riot was not a spontaneous one, as UNMO had always tried to stir anti-PAP sentiments and communal politics among the Singapore Malays. They often used fiery speeches and Utusan Melayu as a tool to propagate pro-Malay sentiments and to sway their support towards UMNO.

The riots occurred around 5 pm, when a few Malay youths were seen to be hitting a Chinese cyclist along Victoria Street, which was intervened against by a Chinese constable. The riots which occurred around Victoria and Geylang had spread to other parts of Singapore such as Palmer Road and Madras Street. The police force, military and the Gurkha battalion were activated to curb the violence and at 9:30 pm, a curfew was imposed whereby everyone was ordered to stay at home. The riot saw serious damage to private properties, loss of lives, and injuries sustained. According to reports, a total of 220 incidents were recorded with 4 being killed and 178 sustaining some injuries. Close to 20 shophouses owned by the Chinese around Geylang and Jalan Eunos were burnt down. The curfew was lifted at 6 am on 22 July 1964, but clashes and tensions between the Malays and Chinese re-arose, so the curfew was re-imposed at 11:30 am. The racial riots subsided by 24 July 1964, as the number of communal clashes reported was reduced to seven cases. On 2 August, the imposition of the curfew since 21 July was completely lifted and the high police and military supervision was removed.

After the July riots, a period of peace was broken by another riot on 2 September 1964. This riot was triggered by the murder of a Malay trishaw rider along Geylang Serai and this incident sparked attempts of stabbings and heightened violence. 13 people were killed, 106 sustained injuries and 1,439 were arrested.

Following the July riots, the Singapore government requested that the Malaysian federal government appoint a commission of inquiry to investigate the causes of the riots, but this was declined by the Malaysian government. Following the September riots, the Malaysian government finally agreed to form such a commission, with closed-door hearings beginning in April 1965, but the findings of the report have remained confidential.

The racial riots in July 1964, triggered and intensified the political rift between PAP and UMNO, which led to the separation between Malaysia and Singapore in 1965.

The July 1964 racial riots played a significant role in shaping some of Singapore’s fundamental principles such as multiculturalism and multiracialism after independence from Malaysia. The Singapore Constitution emphasised the need to adopt non-discriminatory policies based on race or religion by guaranteeing the grant of minority rights and ensuring that the minorities in Singapore are not mistreated. During Racial Harmony Day, schools recall the racial riots that occurred but the emphasis on the event is focused on the tension between the Malays and the Chinese rather than on the political and ideological differences between UMNO and PAP.