The Shree Kolayat Fair, also known as the Kapil Muni Fair, is one of Rajasthan’s most vibrant and culturally rich festivals. Held annually in the town of Kolayat, near Bikaner, this fair is a significant religious and social event that attracts thousands of devotees and tourists. The fair is dedicated to Kapil Muni, a revered sage in Hindu mythology, and is marked by a series of rituals, cultural performances, and communal activities.

The origins of the Shree Kolayat Fair are deeply rooted in Hindu mythology and the ancient history of Rajasthan. The town of Kolayat is believed to be where Kapil Muni, an incarnation of Lord Vishnu, meditated and attained enlightenment. According to legend, Kapil Muni was a great sage and philosopher who composed the “Sankhya Darshan,” one of the six classical systems of Indian philosophy.

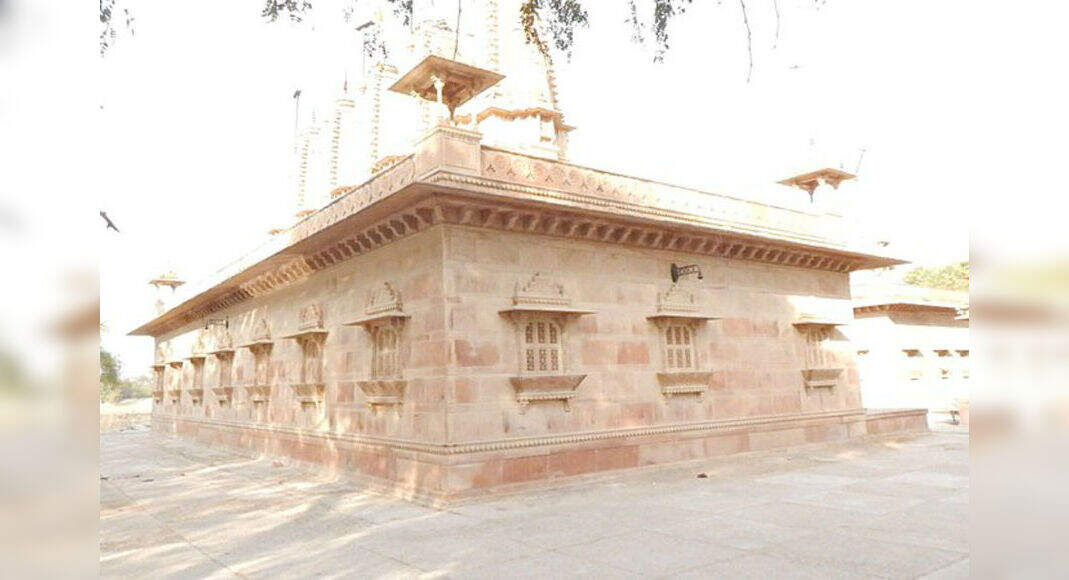

Kolayat is home to the Kapil Muni Temple, which stands by the side of a large lake known as Kolayat Lake. The lake is considered sacred, and its waters are believed to have purifying properties. The Shree Kolayat Fair is held in honour of Kapil Muni and is a time for devotees to pay homage to the sage, seek blessings, and take part in various religious and cultural activities.

The Shree Kolayat Fair is steeped in mythology and legends that add to its spiritual significance. One of the central myths associated with the fair revolves around Kapil Muni’s penance and the sanctity of Kolayat Lake. Kapil Muni is regarded as an incarnation of Lord Vishnu and is credited with the authorship of the Sankhya philosophy, which emphasises the dualism of matter and spirit. According to legend, Kapil Muni chose Kolayat as his place of meditation due to its serene and tranquil environment. It is said that his intense penance and meditation at Kolayat Lake sanctified the waters, making them capable of absolving sins and granting spiritual purification. Another legend tells of a time when the sage’s meditation was disturbed by a group of celestial beings. In his anger, Kapil Muni cursed them, but later, out of compassion, he granted them the boon that anyone who bathed in the lake during the fair would be absolved of their sins. This belief continues to draw thousands of devotees to Kolayat Lake each year.

Another significant myth associated with Kapil Muni and Kolayat Lake involves King Sagara and his sons. According to the legend, King Sagara performed the Ashwamedha Yagna (a horse sacrifice ritual) to assert his supremacy. Indra, the king of gods, became jealous and stole the sacrificial horse, hiding it in the hermitage of Kapil Muni. King Sagara’s 60,000 sons searched for the horse and eventually found it at Kapil Muni’s hermitage. Mistaking the sage for the thief, they disturbed his meditation. In his anger, Kapil Muni reduced them to ashes with his fiery gaze. The king’s descendants later performed penance to appease the sage and were instructed to bathe in Kolayat Lake to purify their souls and attain salvation.

The Shree Kolayat Fair blends religious rituals, cultural performances, and communal activities. The fair typically takes place in the month of Kartik, around October-November according to the Gregorian calendar and culminates on Kartik Purnima, the full moon day of Kartik.

One of the most important rituals of the Shree Kolayat Fair is the holy dip in Kolayat Lake. Devotees believe that bathing in the lake during the fair absolves them of their sins and grants spiritual purification. The lake is surrounded by 52 ghats or bathing steps, and each ghat has its significance. On Kartik Purnima, one sees the highest number of devotees taking the holy dip, creating a vibrant and bustling atmosphere.

Another significant ritual is the offering of diyas or earthen lamps to the lake. Devotees light diyas and set them afloat on the waters of Kolayat Lake as an offering to Kapil Muni. The sight of thousands of diyas floating on the lake creates a mesmerising and serene ambiance, symbolising the triumph of light over darkness and good over evil.

The Kapil Muni Temple, located on the banks of Kolayat Lake, is the focal point of the fair. Devotees visit the temple to offer prayers, seek blessings, and perform rituals to honour Kapil Muni. The temple is beautifully decorated during the fair, and special pujas or worship ceremonies are conducted by the priests.

The Shree Kolayat Fair is also known for its cattle trading activities. Farmers and traders from various parts of Rajasthan and neighbouring states bring their livestock to the fair for trading. The cattle market is a bustling hub of activity, with a wide variety of livestock, including cows, camels, goats, and horses, being bought and sold. The trading of livestock is an essential aspect of the fair, reflecting the agrarian lifestyle of the region.

The fair is a celebration of Rajasthani culture and heritage, with a variety of cultural performances taking place throughout the event. Folk music and dance performances, puppet shows, and traditional Rajasthani plays are some of the highlights. These performances provide entertainment for the visitors and offer a glimpse into the rich cultural traditions of Rajasthan.

Community feasts are an integral part of the Shree Kolayat Fair. Devotees and visitors come together to share meals, fostering a sense of community and camaraderie. The feasts typically include traditional Rajasthani dishes, and the food is often prepared and served by volunteers.

The fair attracts pilgrims from various parts of India, and many of them undertake long journeys to reach Kolayat. Pilgrims often travel in groups, singing devotional songs and carrying flags and banners. Processions are a common sight during the fair, with devotees carrying idols of Kapil Muni and other deities through the streets.

Kartik Purnima, the full moon day of the Hindu month of Kartik, holds special significance in Hinduism and is considered an auspicious day for various religious activities. The Shree Kolayat Fair culminates on this day, and it is believed that the spiritual benefits of participating in the fair are magnified on Kartik Purnima.

Kartik Purnima is associated with several important Hindu deities and events. It is believed to be the day when Lord Vishnu incarnated as Matsya, his fish avatar to save the Vedas from the demon Hayagriva. It is also considered the day when Lord Shiva defeated the demon Tripurasura, leading to the celebration of Tripuri Purnima.

In the context of the Shree Kolayat Fair, Kartik Purnima is the day when the blessings of Kapil Muni are most potent. Devotees believe that performing rituals and taking a holy dip in Kolayat Lake on this day can lead to the absolution of sins and the attainment of spiritual merit.

The rituals on Kartik Purnima at the Shree Kolayat Fair are elaborate and deeply symbolic. Devotees wake up early in the morning and take a holy dip in the lake at sunrise. They then visit the Kapil Muni Temple to offer prayers and seek blessings. Special pujas and havans or rituals with the holy fire are conducted by the priests, and devotees participate in these ceremonies with great devotion. In the evening, the lake is illuminated with thousands of diyas, creating a breathtaking spectacle. Devotees offer the diyas to the lake, and the sight of the floating lamps is a symbol of hope, faith, and spiritual enlightenment.

The Shree Kolayat Fair is not just a religious event; it is a significant cultural and social gathering that has a profound impact on the local community and the region as a whole. The fair provides a substantial economic boost to the town of Kolayat and the surrounding areas. The influx of pilgrims and tourists leads to increased business for local vendors, artisans, and traders. The cattle market, in particular, is a major economic activity, with significant transactions taking place during the fair. The cultural performances and activities at the fair play a crucial role in promoting and preserving Rajasthani culture. Folk music, dance, and traditional arts are showcased, providing a platform for local artists and performers. The fair also attracts cultural enthusiasts and researchers who are interested in studying and documenting the rich heritage of Rajasthan.

The Shree Kolayat Fair fosters social cohesion and community spirit. It brings together people from different backgrounds and regions, creating an environment of unity and harmony. The communal activities, such as feasts and processions, encourage social interaction and strengthen bonds within the community. While the Shree Kolayat Fair continues to be a vibrant and significant event, it faces several challenges in the modern era. Efforts are being made to address these challenges and ensure the preservation of the fair’s cultural and religious significance. The large number of visitors to the fair can lead to environmental issues, such as pollution and waste management challenges. Efforts are being made to promote eco-friendly practices, such as the use of biodegradable materials and proper waste disposal systems.

Awareness campaigns are also conducted to educate visitors about the importance of preserving the natural environment of Kolayat Lake. With the influence of modernisation and changing lifestyles, there is a risk of losing traditional practices and rituals associated with the fair. Cultural preservation initiatives, such as documentation and promotion of traditional arts, are being undertaken to ensure that the heritage of the Shree Kolayat Fair is passed down to future generations. To accommodate the growing number of visitors, there is a need for improved infrastructure and facilities. This includes better transportation, accommodation, sanitation, and medical services. The local government and community organisations are working together to enhance the infrastructure while maintaining the cultural integrity of the fair.

The Shree Kolayat Fair is a celebration of faith, culture, and community that holds a special place in the hearts of the people of Rajasthan. It is a time when devotees come together to honor Kapil Muni, seek spiritual purification, and celebrate the rich cultural heritage of the region. The fair’s vibrant rituals, cultural performances, and communal activities create an atmosphere of joy and devotion, making it a unique and memorable experience for all who attend. As the fair continues to evolve and adapt to modern challenges, it remains a testament to the enduring traditions and values of the Garo people. The Shree Kolayat Fair is not just a festival; it is a living tradition that connects the past with the present and offers a glimpse into the spiritual and cultural richness of Rajasthan.