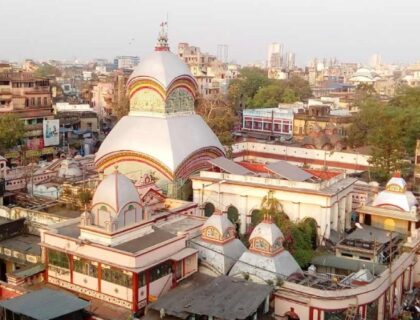

Vimala Temple, Puri, Odisha

Nestled within the renowned Jagannath Temple complex in Puri, the Vimala Temple is an ancient shrine, dedicated to Goddess Vimala, also known as Bimala. The Vimala Temple’s origins stretch back centuries, with the central icon of the goddess dating to the 6th century. However, the current structure, based on its architectural style, is believed to have been constructed in the 9th century during the reign of the Eastern Ganga dynasty. This temple was likely built upon the ruins of an earlier shrine, showcasing the site’s long-standing spiritual significance.

According to the Madala Panji, a chronicle of the Jagannath Temple, the temple was constructed by Yayati Keshari, a ruler of the Somavashi Dynasty of South Kosala. This could refer to either King Yayati I (c. 922–955) or Yayati II (c. 1025–1040), known as Yayati Keshari. Interestingly, some scholars believe that the Vimala Temple may predate even the central Jagannath shrine, highlighting its paramount importance in the religious landscape of Puri.

The Vimala Temple is a masterpiece of Odishan temple architecture, built in the distinctive Deula style. The temple complex consists of four main components. The Vimana is the structure containing the sanctum sanctorum while the Jagamohana is the assembly hall. The Nata-mandapa is the festival hall and the Bhoga-mandapa is the hall of offerings. Constructed primarily of sandstone and laterite, the temple faces east and is situated in the south-west corner of the inner enclosure of the Jagannath temple complex, next to the sacred Rohini Kunda pond.

The temple’s architecture bears similarities to the 9th-century shrine of Narasimha near the Mukti-mandapa in the Jagannath temple complex, further supporting its dating. The intricate carvings on the temple walls and the unique architecture offer visitors a glimpse into the rich artistic traditions of ancient Odisha. In 2005, the temple underwent significant renovations to preserve its original grandeur while enhancing visitor accessibility. Today, it is maintained by the Archaeological Survey of India, Bhubaneswar Circle, ensuring its continued preservation for future generations.

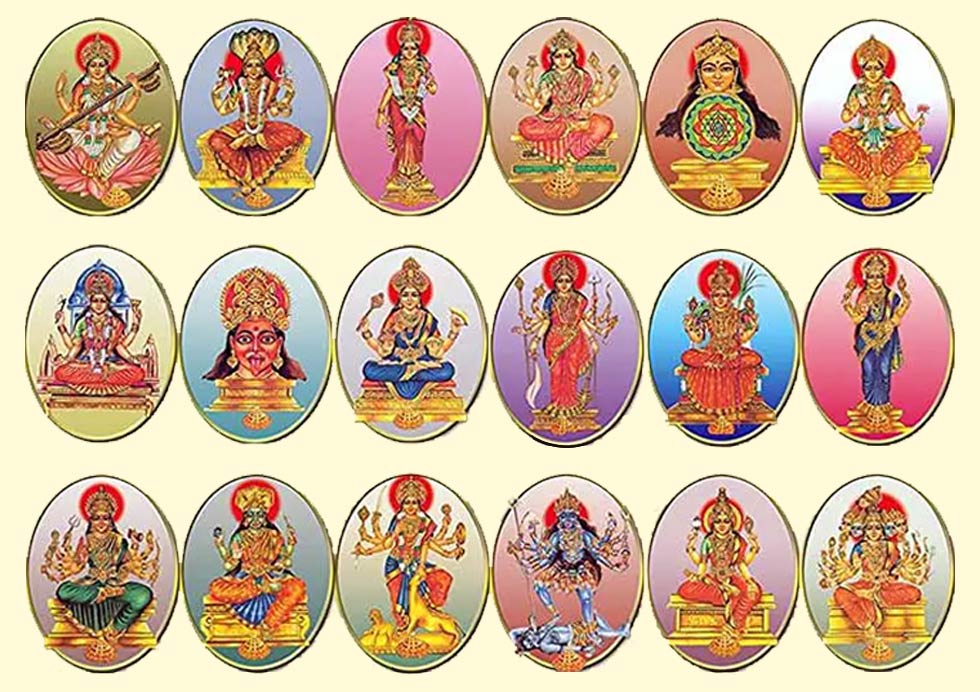

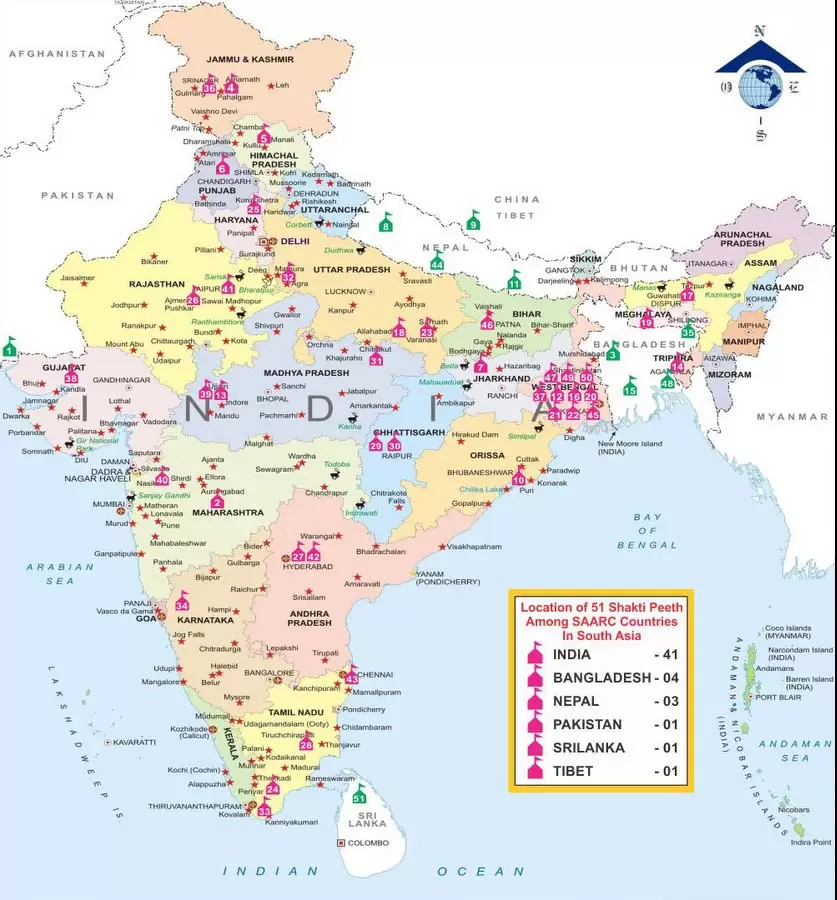

The Vimala Temple holds a special place among Hindu shrines as one of the four Adi Shaktipeethas, considered the oldest and most significant among all Shakti Peethas. According to tradition, this site is where Sati’s navel fell after her body was dismembered. However, another popular belief claims it was Sati’s left foot that fell at this location.

Several features set the Vimala Temple apart from other shrines. The temple holds particular importance for followers of Tantric traditions and Shakta worshippers, who revere it even more than the main Jagannath shrine. Goddess Vimala is considered the tantric consort of Lord Jagannath and is believed to be the guardian of the entire temple complex. Devotees traditionally pay respect to Goddess Vimala before worshipping Lord Jagannath in the main temple. The food offered to Lord Jagannath is not considered Mahaprasad until it has been offered to Goddess Vimala. The four-armed statue of Goddess Vimala holds a rosary, an akshyamala, a pitcher of amrita or Amritakalasa, and an object interpreted by some as a nagini or a Nagaphasa. The fourth arm displays the mudra of blessing. Uniquely, at this Shakti Peetha, Lord Vishnu, in the form of Jagannath, is considered the Bhairava, symbolising the oneness of divine energies.

The Vimala Temple is a hub of vibrant rituals and festivals throughout the year. The temple follows a strict schedule of daily worship rituals performed by specially trained priests. Unlike in other parts of India, Durga Puja at the Vimala Temple is a 16-day celebration culminating in Vijayadashami. During this festival, the Gajapati King of Puri worships the Goddess on the final day. A unique ritual involves offering the food prepared for Lord Jagannath to Goddess Vimala before it is considered Mahaprasad. During Durga Puja, separate non-vegetarian food is cooked and offered to the goddess, a departure from the usual vegetarian offerings in the Jagannath Temple. During the famous Ratha Yatra festival, the deities of Jagannath Temple are offered food only after Goddess Vimala is served, underscoring her significance.

The rituals at the Vimala Temple have evolved over time, reflecting changing social and religious norms. Historically, the temple was known for Tantric practices, including the Panchamakara ritual, which involved fish, meat, liquor, parched grain, and ritual intercourse. However, these practices have been modified over the centuries. King Narasimhadeva, who ruled between 1623 and 1647, ended the meat and fish offerings to the goddess. Today, while vegetarian offerings are the norm, the goddess is still offered meat and fish on special occasions, maintaining a link to the temple’s Tantric past.

The Vimala Temple has had a profound impact on the cultural and spiritual landscape of Puri and beyond. As part of the larger Jagannath Temple complex, it attracts millions of devotees annually, contributing significantly to the local economy and tourism. The temple plays a crucial role in preserving ancient Tantric and Shakta traditions, even as Vaishnavism has become the dominant tradition in the Jagannath Temple complex. The temple exemplifies the syncretic nature of Hinduism, where Vaishnava and Shakta traditions coexist harmoniously. Devotees of Vishnu consider Vimala as a form of Lakshmi, while Shaivites view her as a form of Parvati. The temple serves as a venue for traditional Indian classical music and dance performances, particularly during festivals, contributing to the preservation and promotion of these art forms.

In our modern world, where the interplay of various religious traditions is often a source of tension, the Vimala Temple offers a model of harmonious coexistence. Here, Vaishnava and Shakta traditions blend seamlessly, reminding us of the underlying unity of diverse spiritual paths.

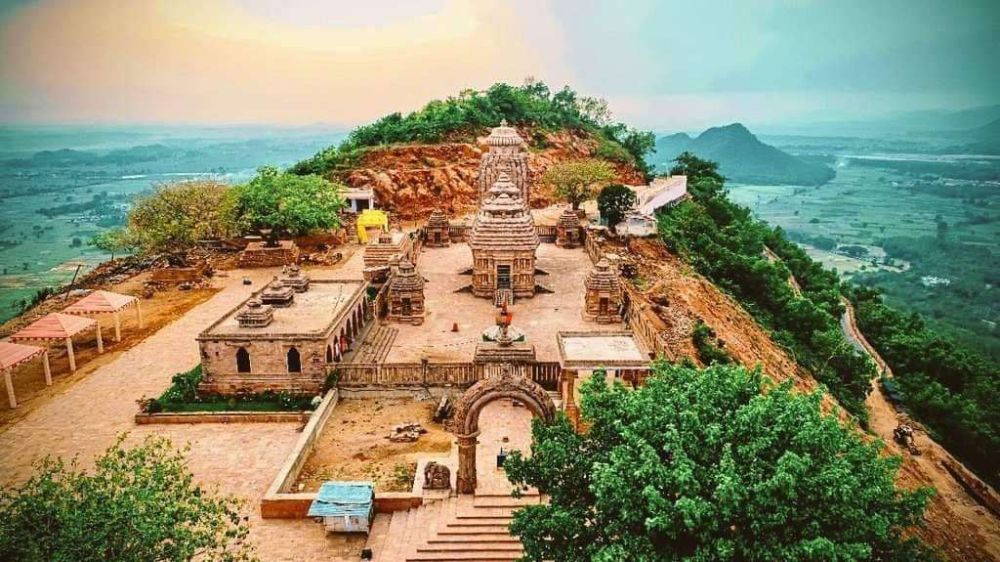

Tara Tarini Temple, Ganjam, Odisha

Nestled atop the verdant Kumari hills in Ganjam district of Odisha, overlooking the serene Rushikulya river, the Tara Tarini Temple is dedicated to the twin goddesses Tara and Tarini. As one of the four Adi Shakti Peethas, it is considered among the oldest and most significant centres of divine feminine power in Hinduism.

The roots of the Tara Tarini Temple stretch deep into antiquity, with its spiritual significance predating its current structure. The present temple, built in the 17th century, stands as a testament to centuries of devotion and reverence. However, the site’s sacred status extends far beyond the current edifice. Archaeological evidence and ancient texts suggest that this location has been a place of worship for over two millennia. The nearby Jaugada Rock Edict, an important monument built by Emperor Ashoka over 2000 years ago, hints at the area’s historical and spiritual importance. Some scholars believe that in ancient times, this place was a sacred Buddhist site, highlighting the syncretic nature of Indian spirituality.

The Kalika Purana, an ancient Hindu text written approximately a thousand years ago, describes the location of the Tara Tarini Shaktipeeth, further cementing its longstanding significance in Hindu cosmology. Through the ages, the Tara Tarini temple has continued to be an important place of worship for both Buddhist and Hindu tantra practitioners, showcasing the fluid and inclusive nature of Indian spiritual traditions.

The Tara Tarini Temple’s status as a Shakti Peetha imbues it with profound spiritual significance. It is believed to be the Stana Peetha or breast shrine of Adi Shakti, the supreme mother goddess. This association with the divine feminine principle makes it a potent source of spiritual energy for devotees. What sets Tara Tarini apart is its unique representation of the divine feminine as twin goddesses. Tara and Tarini are considered manifestations of Adi Shakti, embodying various aspects of the supreme goddess known by names such as Mahakali, Mahalakshmi, Mahasaraswati, Durga, and Parvati.

The Bhairavs associated with this Shakti Peetha are Someshwar or Tumkeswar, the bhairav of the elder sister Devi Tara, and Udayeshwar or Utkeswar, the bhairav of the younger sister Devi Tarini. Their temples are located on the path leading to the main Shakti temple, creating a holistic spiritual landscape.

Several features distinguish the Tara Tarini Temple from other shrines. The temple is unique in its worship of twin goddesses, Tara and Tarini, each with distinct iconography and attributes. The main temple houses Swayambhu statues of the goddesses Tara and Tarini, believed to have appeared by divine will rather than human craftsmanship. The temple architecture showcases a beautiful fusion of Kalinga and Dravidian styles, featuring a conical spire and intricate carvings. Situated at an elevation of 708 feet, the temple offers panoramic views of the surrounding landscape. A flight of 999 steps leads from the foot of the hill to the temple, adding to its mystique and the devotees’ sense of pilgrimage. The site’s history as a place of worship spans over two millennia, with evidence of both Buddhist and Hindu influences. Maa Tara is depicted with four arms holding various symbolic items, while Maa Tarini is shown with two arms holding a sword and a lotus, symbolising their roles as protectors and providers.

The Tara Tarini Temple is a masterpiece of Odishan temple architecture, built in the distinctive Kalinga style. The temple complex consists of several key components. The central temple houses the Swayambhu statues of Tara and Tarini, made of stone and adorned with gold and silver. A towering archway decorated with intricate carvings marks the main entrance, while the inner sanctum features colorful murals depicting the divine stories of the goddesses. A large courtyard surrounds the main shrine, accommodating devotees during festivals and rituals. Smaller temples dedicated to other deities dot the complex, and the temple houses several deities known as utsav murtis, used in processions during festivals like the Rath Yatra. The use of sandstone and laterite in the temple’s construction not only adds to its aesthetic appeal but also reflects the region’s geological heritage. The intricate carvings on the temple walls showcase the exceptional skill of ancient Odishan artisans and serve as a visual narrative of Hindu mythology and local legends.

The Tara Tarini Temple is a hub of vibrant rituals and devotional practices throughout the year. The temple follows a strict schedule of daily worship rituals performed by specially trained priests. Food offerings to the goddesses play a crucial role in the temple’s rituals, with the prasad being highly revered by devotees. Many devotees bring their children to the temple for the mundan, or the first haircut ritual as an offering to the goddesses for their protection. Given its historical association with Tantric traditions, the temple continues to be an important centre for certain Tantric rituals, though many have been modified over time to align with contemporary practices. During the famous chariot festival, the utsav murtis of the goddesses are taken out in a grand procession, allowing devotees who cannot climb the hill to receive their blessings.

The Tara Tarini Temple comes alive with numerous festivals throughout the year, attracting thousands of devotees from across India and beyond. Chaitra Parba or the Tara Tarini Mela is the most important festival held at the temple, occurring annually during March and April. The festival spans the entire month of Chaitra, with each Tuesday being particularly auspicious. The third Tuesday witnesses the grandest celebrations, drawing over 50,000 devotees. During the nine-day Navaratri festival, the temple sees a surge of pilgrims coming to worship the goddesses as manifestations of Goddess Durga. The temple is elaborately decorated, and special pujas are conducted. Held in January, the Sankranti Mela festival marks the sun’s transit into Capricorn and is celebrated with great fervour at the temple. Coinciding with Holi, Dol Purnima is a spring festival that sees joyous celebrations while Saradiya Parba is an autumn festival, coinciding with Durga Puja, that is another important event in the temple’s calendar. Celebrated during Diwali, Shyamakali Parba adds to the temple’s yearly cycle of celebrations.

The Tara Tarini Temple holds immense cultural significance in the region, influencing local traditions, art, and folklore. Goddesses Tara and Tarini are regarded as the presiding deities or the Ista Devi in most households in Southern Odisha. According to one local legend, Tara and Tarini were beautiful sisters from Padmapur village known for their generosity. Their kindness led Goddess Tara to make them divine, ensuring they would be worshipped forever. The site where the temple stands is believed to be the battleground where the goddesses defeated the demons Sumbha and Nisumbha, making it a symbol of divine victory and protection. The temple’s architecture, iconography, and associated legends have inspired various forms of local art, including paintings, sculptures, and performing arts. The temple has fostered a strong tradition of pilgrimage in the region, with devotees undertaking arduous journeys to seek the blessings of the goddesses.

The temple’s unique representation of twin goddesses, its ancient history, and its vibrant traditions make it a crucial piece in understanding the spiritual landscape of Odisha and India as a whole. The story of the Tara Tarini Temple is ultimately a story of continuity and change – of ancient traditions persisting through centuries of social and religious evolution.