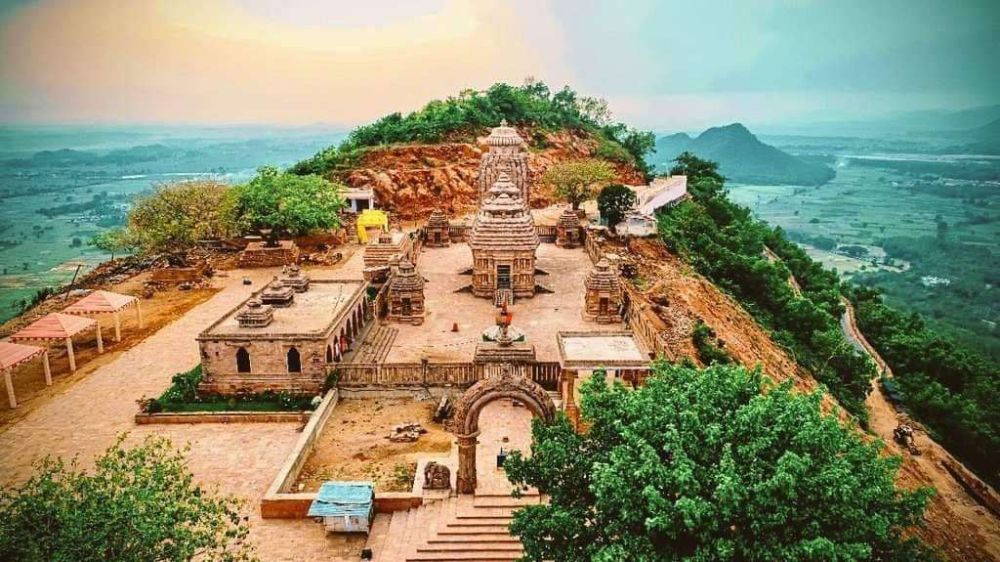

Kukkuteswara Swamy Temple, Kakinada Port Town, Andhra Pradesh

Located in the historic town of Pithapuram, near Kakinada Port Town, the Puruhutika Shaktipeeth, also known as the Kukkuteswara Swamy Temple is dedicated to Goddess Puruhutika and Lord Kukkuteswara. The origins of the Puruhutika Shaktipeeth extend deep into Hindu mythology and historical texts. This temple is not only revered in contemporary times but has also been mentioned in the Skanda Purana, Srinatha’s Bheemeswara Puranamu, and Samudragupta’s Allahabad stone pillar inscription.

The Pithapuram Puruhutika Devi temple is mentioned in texts that were written as early as the 8th century. Rishi Vyasa, in one of his prominent works, Skanda Purana, describes in detail his trip to the Pithapuram temple he undertook along with his disciples. The 15th-century Telugu poet Srinatha also mentions this temple in Bheemeswara Purana. He lists this temple as one of the four places that are Moksha Sthaanas – abodes of liberation. Therefore, one can say that this place is parallel to Varanasi, Kedarnath and Kumbakonam in terms of divinity.

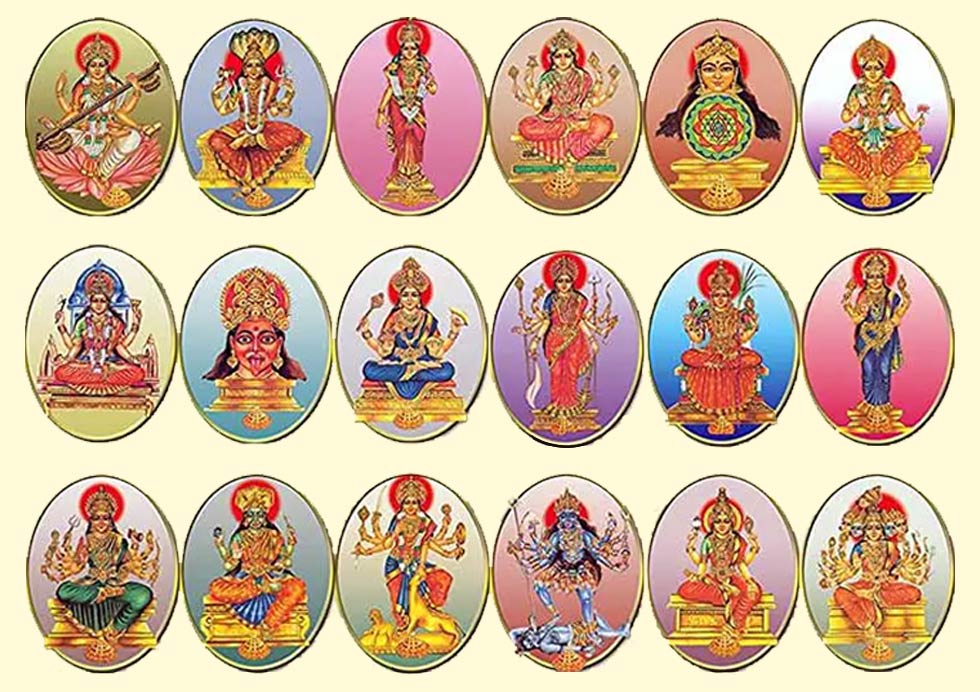

The Puruhutika Shaktipeeth is recognised as one of the Asta Dasha or eighteen Shakti Peethas scattered across the Indian subcontinent. After the Daksha Yagna, Goddess Sati Devi’s back fell down in this area, because of which this place was earlier called Puruhoothika puram, later changed to Peetika Puram, and finally to Pithapuram. This temple is considered as the 10th Sakthi Peetham of the 18 Shakti Peethas. At the Puruhutika Shaktipeeth, the goddess is worshipped as Sri Raja Rajeswari Devi. Her consort, Lord Shiva, is worshipped as Sri Kukkuteswara Swamy.

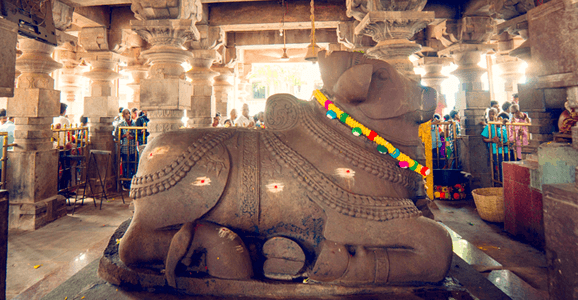

The presiding deity is Lord Shiva, who reveals himself in the form of a Spatika Linga. This is a Swayambhu Linga of white marble and is about two feet in height. The Linga resembles that of a cock; hence Lord Shiva is called Sri Kukkuteswara Swamy. There is a huge beautiful idol of Nandi the bull made from a single stone in front of the temple. Goddess Puruhutika Devi is in a standing position. The idol of Goddess Puruhutika is made from granite and is adorned with jewels, a Kirit and robed in silks. The deity has four palms and Starting from the lower right to the lower left, Goddess Devi’s lower right hand has a bag full of seeds, an axe or parashu, a lotus and a Madhu Patra.

This place is one among the Trigaya Kshetrams and has become famous as Pada Gaya Kshetram. Gaya Asura, a powerful demon who laid his body at the behest of Brahma for doing a great yagna for the betterment of people, was so huge that his head rested in Bihar and his legs reached Pithapuram. The place where his legs rested was a pond which came to be known as Pada Gaya Sarovar. It is believed that whoever bathes in this sacred pond will be relieved of their sins. The Kunti Madhavaswamy temple adjacent to Kukkuteswara temple is another major temple in the town. Kunti is said to have installed the image in this place, and so is called Kunti Madhavaswamy. This deity is said to have been worshipped by Vyasa, Valmiki and Agastya in the past. The Swayambhu Sri Dattatreya Swamy is also in the temple complex. Sripada Srivallabha Swamy’s idol is worshipped separately in the same complex. It is the only place where an idol of Sri Datta incarnation is worshipped. There are other shrines of various gods like Sri Rama, Ayyappa, Sri Vishveshwara and Sri Annapurna Devi, Sri Durga Devi.

Devotees can participate in Nitya pujas or daily worship, Sani Trayodasi, the Dassera festival in September/October, the Kartik Masam in October/November, Maha Shivaratri in February/March, Swamy Vari Kalyanam or the divine wedding and Radotsavam or the Chariot Festival during February/March, and Magha Masam Trayodasi in February/March. Maha Shivaratri, Sarannavarathri and Kartika Masam are the main festivals celebrated at this temple. The temple celebrates Devi Navaratri in Dussehra season. Annual festivals celebrated here are different for different deities like Maghabahula Ekadasi for Kukkuteswara, Suddha Ekadasi for Kunti Madhava, Palguna for Kumaraswamy and Karthikamasa for Venugopalaswamy.

According to legend, the demon Gayasura was a devout devotee of Lord Vishnu who did penance for years. Lord Vishnu appeared before him and granted his wish that anyone who sees him achieve Moksha. Gayasura used his spiritual powers to enlarge his body so that everyone on Earth could be saved. The God of Heaven, Indra, and the Devas expressed concern to the three deities about the creation’s imbalance. Lord Vishnu, Brahma, and Siva disguised themselves as Brahmins and approached Gayasura in search of Yajna space. This legend is closely tied to the Pada Gaya Sarovar in the temple complex.

There are two sects of worshippers of Devi. The first worshipped the Devi as Puruhootha Lakshmi. She is meditating with a lotus and Madhu Patra in her palms. This sect observed the Samayachar shape of worship. The second sect worshipped the Devi as Puruhoothamba. She is meditating with an axe or Parashu and a bag of seeds in her fingers. This sect followed the Vamachara shape of worship and the unique deity was buried under the temple.

According to mythology, this temple is linked to the demon king Gayasura, who was granted a boon that made him invincible. However, when his tyranny grew unbearable, the gods sought the Trimurtis for help. The Trimurtis—Lord Shiva, Lord Vishnu, and Lord Brahma—devised a plan to subdue him. They approached Gayasura and requested him to offer his body for a Yagna or sacrificial ritual, as his body was considered sacred. Gayasura agreed and lay down, stretching his body across the land. His head rested at Gaya in present-day Bihar, his navel at Jajpur in Odisha, and his feet at Pithapuram in Andhra Pradesh. The Yagna was to last seven days, during which Gayasura was forbidden from moving. On the sixth day, Lord Shiva took the form of a rooster or Kukkuta and crowed at midnight, tricking Gayasura into believing that the ritual was complete. Thinking it was dawn, Gayasura moved before the Yagna concluded, breaking his vow. The Trimurtis then revealed their true forms and explained that his movement had disrupted the ritual. Realizing his mistake, Gayasura accepted his fate gracefully. The Trimurtis blessed him, declaring that his body would sanctify the places where it lay. The pond where Gayasura’s feet rested became known as Pada Gaya Sarovar, and it is believed that taking a dip in this sacred pond cleanses sins and grants liberation.

The Kukkuteswara Swamy Temple is also closely linked to Sri Pada Srivallabha, considered an incarnation of Lord Dattatreya. According to legend, Sri Pada Srivallabha was born in Pithapuram to a devout Brahmin couple named Sumathi and Raja Simha Sharma. The couple had two sons who were blind, deaf, and mute due to their past karmic deeds. Despite their hardships, they remained devoted to Lord Datta Devi and worshipped at Padagaya Kshetram with unwavering faith. One day, during an annual ceremony for their ancestors, a sage disguised as Lord Dattatreya visited their home seeking alms. Sumathi offered food without hesitation, even though her husband was not present—a gesture considered sacrilegious during such rituals. Pleased by her devotion and selflessness, Dattatreya revealed his true form and granted her a boon: he would be born as her son. Thus, Sri Pada Srivallabha incarnated in Pithapuram as their child. He is regarded as one of the greatest saints in Hinduism and is believed to have performed numerous miracles during his lifetime.

The Puruhutika Shaktipeeth, with its blend of myth, history, and living faith, continues to be a powerful force in the religious landscape, inviting all who visit to partake in its timeless spiritual journey. Its unique blend of Shaivite and Shakta traditions, coupled with its rich historical background, makes it a fascinating destination for both devotees and those interested in India’s spiritual heritage.

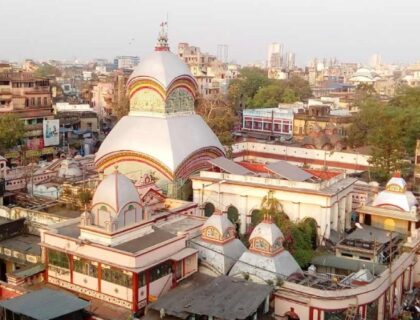

Aranya Devi Temple, Arrah, Bihar

Dedicated to Goddess Aranya Devi, the Aranya Devi Temple is located in Arrah and dates back to antiquity. While the present temple building was established in 2005, the site’s sacred status extends far beyond this recent construction. The name Aranya is derived from the Sanskrit word meaning forest, hinting at the area’s lush past. Archaeological evidence and ancient texts suggest that this location has been a place of worship for millennia. The temple finds mention in various mythological texts, linking it to different eras of Hindu mythology. Some legends associate it with the Satya Yuga, while others connect it to events of the Treta Yuga and Dvapara Yuga.

According to the Devi Bhagavata Purana, this temple is recognised as both a Siddh Pitha and one of the 108 Shakti Pithas. This dual status imbues the site with immense spiritual power, drawing devotees seeking blessings and enlightenment. While the specific body part of Goddess Sati associated with this Shakti Peetha is not mentioned in the available sources, the site’s inclusion in this sacred network underscores its importance in the pantheon of divine feminine energy centres.

The temple houses the idol of Goddess Aranya Devi, considered the presiding deity of Arrah city. This connection to the local geography and culture makes the temple a focal point of regional devotion. While the temple structure is relatively new, it is said that one of the idols of the Goddess was consecrated by the Pandavas during their exile. The temple showcases a blend of ancient and modern architectural styles.

A unique aspect of worship here is the practice of taking vows for the fulfilment of desires. Devotees come to the temple, make their wishes known to the Goddess, and return with offerings of thanksgiving when their desires are fulfilled. This cycle of petition and gratitude forms a core part of the devotional practice at the temple.

The temple is also connected to Lord Rama’s journey to Janakpur for Sita’s swayamvara or marriage ceremony. According to legend, while travelling with Lakshmana and Sage Vishwamitra via Buxar for King Janaka’s Dhanush Yagna, they stopped near present-day Arrah. Sage Vishwamitra narrated to Lord Rama and Lakshmana the glory of Goddess Aranya Devi, who was considered an incarnation of Adishakti and protector of forests. Before crossing the Sonbhadra River, Lord Rama bathed in the nearby Ganges and offered prayers to Goddess Aranya Devi at this sacred site. It is believed that he sought her blessings for success in breaking Lord Shiva’s bow during Sita’s swayamvara.

One of the most prominent legends tied to the Aranya Devi Temple dates back to the Mahabharata period. During their exile, the Pandavas are said to have stayed in the forested region of Arrah. While there, they worshipped Goddess Adishakti, who was revered as the protector of forests and wilderness. One night, Yudhishthira, the eldest Pandava, had a divine dream in which Goddess Aranya Devi appeared. She instructed him to install her idol at the spot where they were staying so that she could continue to protect the region and its people. Following her command, Yudhishthira installed a statue of the goddess at this sacred site. This marked the beginning of her worship in Arrah, and over time, the temple became a revered place of devotion.

Another fascinating story associated with Aranya Devi Temple is linked to King Mordhwaj, who ruled this region during the Dvapara Yuga, the era of Lord Krishna. The king was renowned for his unwavering devotion and generosity. To test his faith and devotion, Lord Krishna disguised himself as a hermit and appeared before King Mordhwaj along with Arjuna, who took on the form of a lion. The hermit claimed that his lion would only eat human flesh and demanded that the king sacrifice his son’s body to feed it. Without hesitation, King Mordhwaj and his queen prepared to saw their son’s body in half to fulfil the hermit’s demand. Moved by their selflessness and devotion, Goddess Durga appeared before them in her divine form as Aranya Devi. She stopped them from carrying out the sacrifice and blessed their family with eternal happiness. The site where this test took place is believed to be where the Aranya Devi Temple now stands. The name Arrah is said to have originated from this incident, deriving from Ara, meaning a saw. Local tradition holds that Bhima, one of the Pandavas, defeated the demon Bakasura at a place called Chakra Ara, which later came to be known as Ara or Arrah.

The temple houses two idols of Goddess Aranya Devi: one representing Saraswati, the Goddess of knowledge and another representing Mahalakshmi, the Goddess of prosperity. These sister goddesses are worshipped together. The temple’s east-facing dome adds architectural significance. Devotees believe that prayers offered here bring protection, prosperity, and the fulfilment of wishes.