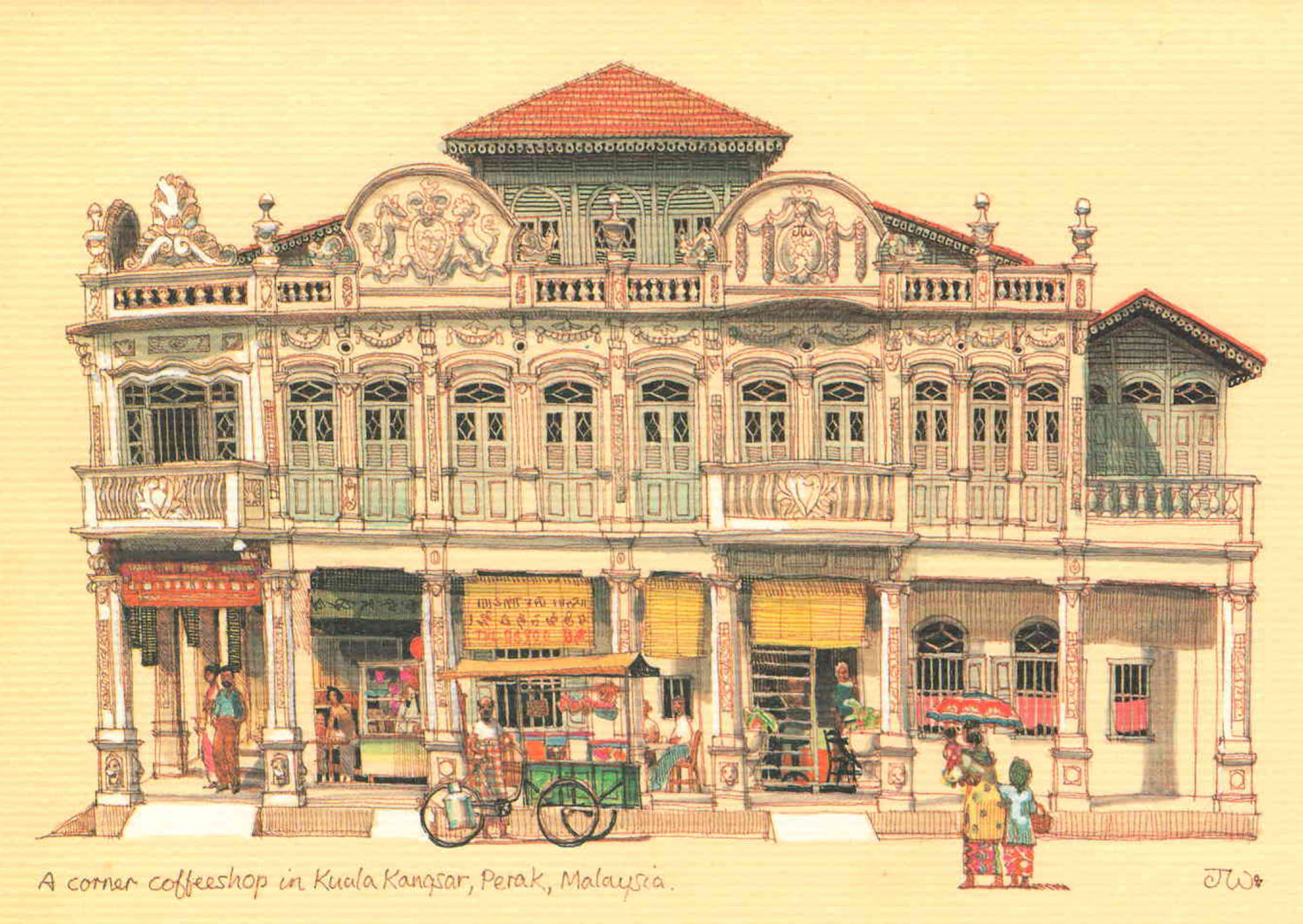

Located on Malaysia’s west coast, the state of Perak borders Kedah to the north, Penang to the northwest, Kelantan and Pahang to the east, and Selangor to the south. Thailand’s Yala and Narathiwat provinces both lie to the northeast. Perak’s capital city, Ipoh, was known historically for its tin-mining activities until the price of the metal dropped, severely affecting the state’s economy. The royal capital remains Kuala Kangsar, where the palace of the Sultan of Perak is located. The state has diverse tropical rainforests and an equatorial climate with the state’s mountain ranges belonging to the Titiwangsa Mountains, part of the larger Tenasserim Hills system that connects Myanmar, Thailand and Malaysia.

The discovery of an ancient skeleton in Perak supplied missing information on the migration of Homo sapiens from mainland Asia through Southeast Asia to the Australian continent. Known as Perak Man, the skeleton is dated at around 10,000 years old. An early Hindu or Buddhist kingdom, followed by several other minor kingdoms, existed before the arrival of Islam. By 1528, a Muslim sultanate began to emerge in Perak, out of the remnants of the Malaccan Sultanate. Although able to resist Siamese occupation for more than two hundred years, the Sultanate was partly controlled by the Sumatra-based Aceh Sultanate. With the arrival of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), and the VOC’s increasing conflicts with Aceh, Perak began to distance itself from Acehnese control. The presence of the English East India Company (EIC) in the nearby Straits Settlements of Penang provided additional protection for the state, with further Siamese attempts to conquer Perak thwarted by British expeditionary forces.

The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 was signed to prevent further conflict between the British and the Dutch which enabled the British to expand their control in the Malay Peninsula without interference from other foreign powers. The 1874 Pangkor Treaty provided for direct British intervention, with Perak appointing a British Resident. Following Perak’s subsequent absorption into the Federated Malay States (FMS), the British reformed administration of the sultanate through a new style of government, actively promoting a market-driven economy and maintaining law and order while combatting the slavery widely practised across Perak at the time.

The three-year Japanese occupation in World War II halted further progress. After the war, Perak became part of the temporary Malayan Union, before being absorbed into the Federation of Malaya. It gained full independence through the Federation, which subsequently became Malaysia on 16 September 1963.

Perak is ethnically, culturally, and linguistically diverse. The state is known for several traditional dances, including bubu, dabus, and labu sayong, the latter name also referring to Perak’s unique traditional pottery. The head of state is the Sultan of Perak, and the head of government is the Menteri Besar. Islam is the state religion, and Malay and English are recognised as the official languages of Perak. Perak’s economy is mainly based on services and manufacturing.

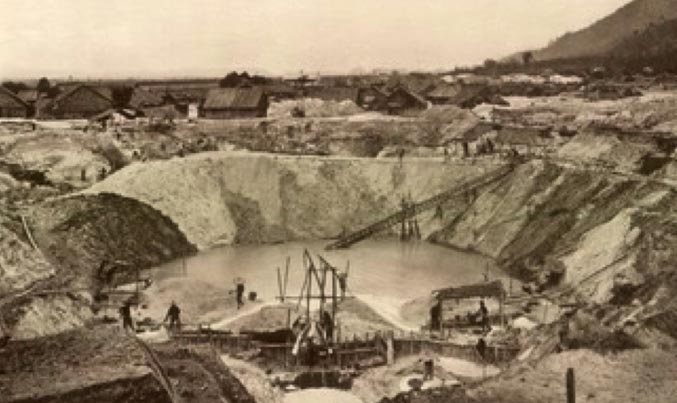

There are many theories about the origin of the name Perak. The most popular theory is silver, which is what Perak means in Malay and is associated with tin mining from the state’s large mineral deposits, reflecting Perak’s position as one of the world’s largest sources of tin. Some local historians have suggested that Perak was named after Malacca’s bendahara, Tun Perak. Other historians believe that the name Perak derives from the Malay phrase kilatan ikan dalam air or the glimmer of fish in water, which looks like silver. Perak has been translated into Arabic as Dār al-Riḍwān, or the abode of grace.

Bukit Bunuh and Kota Tampan are ancient lakeside sites, with the geology of Bukit Bunuh showing evidence of a meteoric impact. The 10,000-year-old skeleton known as Perak Man was found inside the Bukit Gunung Runtuh cave at Bukit Kepala Gajah. Ancient tools discovered in the area of Kota Tampan, including anvils, cores, debitage, and hammerstones, provide information on the migrations of Homo sapiens.

In 1959, a British artillery officer stationed at an inland army base during the Malayan Emergency discovered the Tambun rock art, identified by archaeologists as the largest rock art site in the Malay Peninsula. Most of the paintings are located high above the cave floor, at an elevation of 6–10 metres. Seashells and coral fragments scattered along the cave floor are evidence that the area was once underwater.

The significant numbers of statues of Hindu deities and of the Buddha found in Bidor, Kuala Selensing, Jalong, and Pengkalan Pegoh indicate that, before the arrival of Islam, the inhabitants of Perak were mainly Hindu or Buddhist. The influence of Indian culture and beliefs on society and values in the Malay Peninsula from early times is believed to have culminated in the semi-legendary Gangga Negara kingdom, which, according to the Malay Annals, fell under Siamese rule once upon a time before Raja Suran of Thailand sailed further south down the Malay Peninsula.

By the 15th century, a kingdom named Beruas had come into existence. Inscriptions found on early tombstones of the period show a clear Islamic influence, believed to have originated from the Sultanate of Malacca, the east coast of the Malay Peninsula, and the rural areas of the Perak River. With the spread of Islam, a sultanate subsequently emerged in Perak; the second-oldest Muslim kingdom in the Malay Peninsula after the neighbouring Kedah Sultanate. The Perak Sultanate was formed in the early 16th century on the banks of the Perak River by the eldest son of Mahmud Shah, the 8th Sultan of Malacca, who ascended to the throne as Muzaffar Shah I, the first sultan of Perak, after surviving the capture of Malacca by the Portuguese in 1511 and living quietly for a period in Siak on the island of Sumatra. Perak’s administration became more organised after the Sultanate was established. With the opening of Perak in the 16th century, the state became a source of tin ore and anyone was free to trade in the commodity, although the tin trade did not attract significant attention until the 1610s.

Throughout the 1570s, the Sultanate of Aceh subjected most parts of the Malay Peninsula to continual harassment. Sultan Mansur Shah I’s eldest son, Raja Alauddin Mansur Syah, married an Acehnese princess and subsequently became Sultan of Aceh. The Sultanate of Perak was left without a ruling monarch, and Perak nobles journeyed to Aceh in the same year to ask the new Sultan Alauddin for a successor, who sent his younger brother to become Perak’s third monarch. Sultan Ahmad Tajuddin Shah ruled Perak for seven years, maintaining the unbroken lineage of the Malacca dynasty. Although Perak did fall under the authority of the Acehnese Sultanate, it remained entirely independent of Siamese control for over two hundred years, from 1612. In 1620, the Acehnese sultanate invaded Perak and captured its sultan. After Sultan Sallehuddin Riayat Shah died without an heir in 1635, Aceh’s Sultan Iskandar Thani sent his relative, Raja Sulong, to become the new Perak Sultan Muzaffar Shah II. Aceh’s influence on Perak began to wane when the Dutch East India Company (VOC) arrived in the mid-17th century.

When Perak refused to enter into a contract with the VOC as its northern neighbours had done, a blockade of the Perak River halted the tin trade, causing suffering among Aceh’s merchants. In 1650, Aceh’s Sultana Taj ul-Alam ordered Perak to sign an agreement with the VOC, on condition that the tin trade would be conducted exclusively with Aceh’s merchants. By the following year, 1651, the VOC had secured a monopoly over the tin trade, setting up a store in Perak. Following long competition between Aceh and the VOC over Perak’s tin trade, on 15 December 1653, the two parties jointly signed a treaty with Perak granting the Dutch exclusive rights to tin extracted from mines located in the state.

The early 18th century started with 40 years of civil war where rival princes were bolstered by local chiefs, the Bugis and the Minang, all fighting for a share of tin revenues. The Bugis and several Perak chiefs were successful in ousting the Perak ruler, Sultan Muzaffar Riayat Shah III in 1743. The mid-18th century saw the rule of Sultan Muzaffar ruling inland Perak while the coastal region was ruled by Raja Iskandar, animosity grew between the two as Raja Iskandar was unable to reach the tin-bearing highlands while the sultan had restricted access to the strait. Reconciliation occurred later with Iskandar’s marriage to the sultan’s daughter. His accession in 1752 saw unprecedented peace in Perak, especially due to an alliance, which lasted until 1795 with the Dutch to protect Perak against external attacks. When repeated Burmese invasions resulted in the destruction and defeat of the Siamese Ayutthaya Kingdom in 1767 by the Burmese Konbaung dynasty, neighbouring Malay tributary states began to assert their independence from Siam. To further develop Perak’s tin mines, the Dutch administration suggested that its 17th Sultan, Alauddin Mansur Shah Iskandar Muda, should allow in Chinese miners.

The Fourth Anglo-Dutch War in 1780 adversely affected the tin trade in Perak, and many Chinese miners left. In a move which angered the Siamese court, neighbouring Kedah’s Sultan Abdullah Mukarram Shah then entered into an agreement with the English East India Company, ceding Penang Island to the British in 1786 in exchange for protection.

In 1818, the Dutch monopoly over the tin trade in Perak was renewed, with the signing of a new recognition treaty. The same year, when Perak refused to send a bunga mas tribute to the Siamese court, Rama II of Siam forced Kedah to attack Perak. Siam’s tributary Malay state, the Kingdom of Reman, then illegally operated tin mines in Klian Intan, angering the Sultan of Perak and provoking a dispute that escalated into civil war. Reman, aided by Siam, succeeded in controlling several inland districts. In 1821, Siam invaded and conquered the Sultanate of Kedah, angered by a breach of trust. Siam’s subsequent plan to extend its conquests to the southern territory of Perak[40][65][68] failed after Perak defeated the Siamese forces with the aid of mixed Bugis and Malay reinforcements from the Sultanate of Selangor. As an expression of gratitude to Selangor, Perak authorised Raja Hasan of Selangor to collect taxes and revenue in its territory. This power, however, was soon misused, causing conflict between the two sultanates.

In 1823, the Sultanates of Perak and Selangor signed a joint agreement to block the Dutch tin monopoly in their territories and the EIC policy shifted with the First Anglo-Burmese War in 1824, Siam then becoming an important ally.

In 1873, the ruler of one of Perak’s two local Malay factions, Raja Abdullah Muhammad Shah II, wrote to the Governor of the British Straits Settlements, Andrew Clarke, requesting British assistance, resulting in the Treaty of Pangkor, signed on Pangkor Island on 20 January 1874, under which the British recognised Abdullah as the legitimate Sultan of Perak. In return, the treaty provided for direct British intervention through the appointment of a Resident who would advise the sultan on all matters except religion and customs, and oversee revenue collection and general administration, including maintenance of peace and order. The treaty marked the introduction of a British residential system, with Perak going on to become part of the Federated Malay States (FMS) in 1895.

Under the Anglo-Siamese Treaty, Siam ceded to Great Britain its northern Malay tributary states of Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis, and Terengganu and nearby islands. Exceptions were the Patani region, which remained under Siamese rule, and Perak, which regained the previously lost inland territory that became the Hulu Perak District.

During World War II, the Japanese occupied all of Malaya and Singapore. Under a reform plan proposed by Tokugawa Yoshichika, the five kingdoms of Johor, Terengganu, Kelantan, Kedah-Penang, and Perlis would be restored and federated. Johor would control Perak, Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, and Malacca. An 800-square-mile area in southern Johor would be incorporated into Singapore for defence purposes.

In 1943 the Empire of Japan restored to Thailand the former Malay tributary states of Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis, and Terengganu, which had been ceded by the then-named Siam to the British under the 1909 treaty. The indigenous Orang Asli stayed in the interior during the occupation. Much of their community was befriended by Malayan Communist Party guerrillas, who protected them from outsiders in return for information on the Japanese and their food supplies. Strong resistance came mainly from the ethnic Chinese community, some Malays preferring to collaborate with the Japanese through the Kesatuan Melayu Muda (KMM) movement for Malayan independence.

In 1961, the Prime Minister of the Federation of Malaya, Tunku Abdul Rahman, sought to unite Malaya with the British colonies of North Borneo, Sarawak, and Singapore. Despite opposition from the governments of both Indonesia and the Philippines, the Federation came into being on 16 September 1963. With the end of British rule in Malaya and the subsequent formation of the Federation of Malaysia, new factories were built and many new suburbs developed in Perak.

Perak is the second largest Malaysian state on the Malay Peninsula, and the fourth largest in Malaysia. Mangrove forests grow along most of Perak’s coast, except for Pangkor Island, with its rich flora and fauna, where several of the country’s forest reserves are located. Perak’s geology is characterised by eruptive masses, which form its hills and mountain ranges. The state is divided by three mountain chains into the three plains of Kinta, Larut and Perak, running parallel to the coast. An extensive network of rivers originates from the inland mountain ranges and hills. The jungles of Perak are highly biodiverse.

The tertiary sector is Perak’s main economic sector. In 2018, the state was the second most popular destination for domestic tourists in Malaysia, after the state of Pahang. The state also contains several natural attractions, including bird sanctuaries, caves, forest reserves, islands, limestone cliffs, mountains, and white sandy beaches.

In the next part, let’s learn more about Perak’s capital, Ipoh.