George Town

Penang’s capital, George Town is the core city of the George Town Conurbation, Malaysia’s second-largest metropolitan area with a population of 2.84 million. The city proper covers an area of 306 sq. km and was home to a population of 794,313 as of 2020.

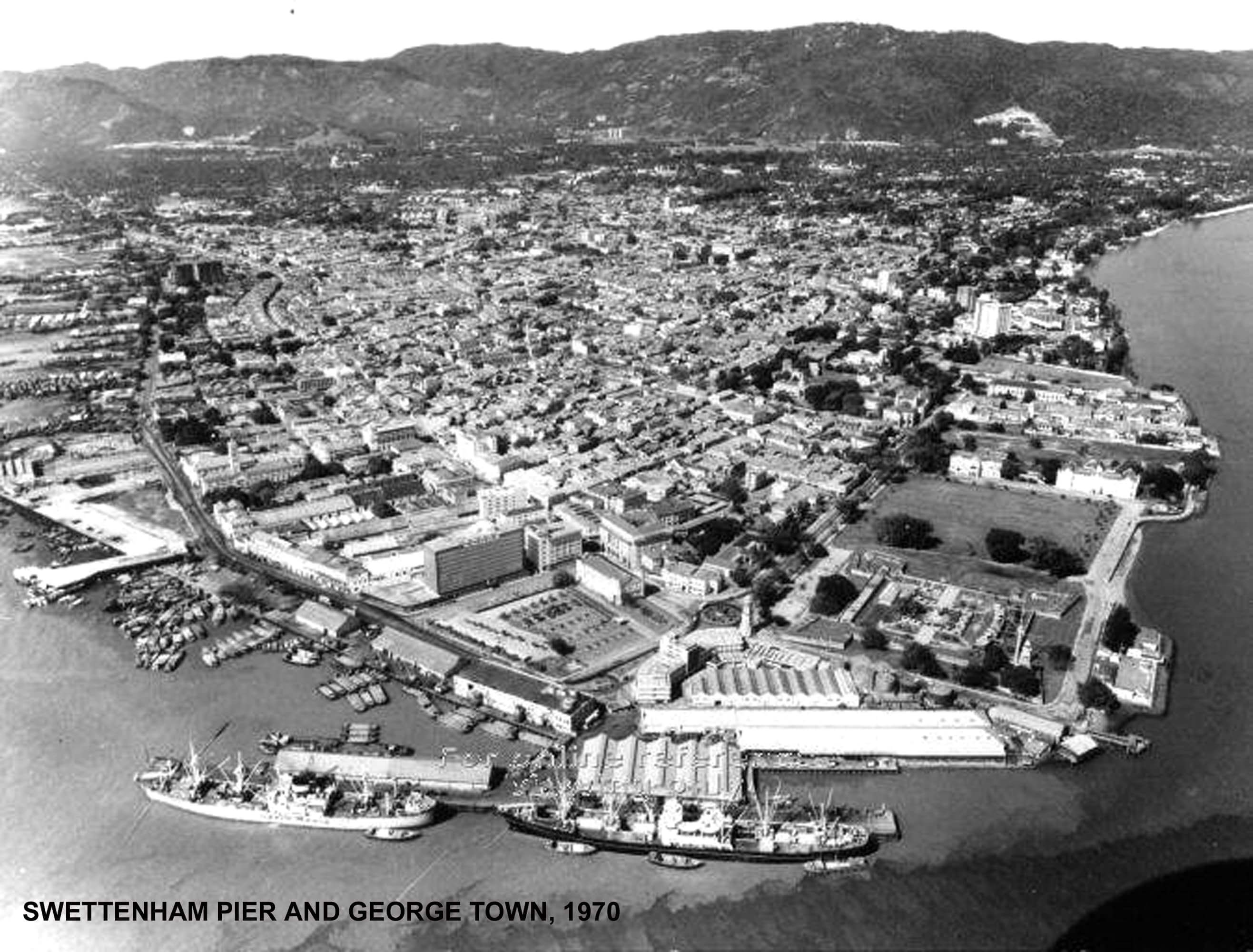

Initially established as an entrepôt by Francis Light in 1786, George Town now serves as the economic hub for northern Malaysia and contributes nearly 8% of the country’s disposable income, second only to Kuala Lumpur. George Town remains the financial centre of northern Malaysia, while the Bayan Lepas Free Industrial Zone, a high-tech manufacturing hub in the city’s south, has become the nucleus of Malaysia’s electronics industry. It is also the primary medical tourism hub in the country. In recent years, Swettenham Pier has emerged as the busiest port of call in Malaysia for cruise shipping.

George Town was the first British settlement in Southeast Asia and its proximity to maritime routes along the Strait of Malacca attracted an influx of immigrants from various parts of Asia in the early 19th century. Following rapid growth in its early years, it became the capital of the Straits Settlements in 1826, only to lose its administrative status to Singapore in 1832. The Straits Settlements became a British crown colony in 1867. George Town was subjugated by the Empire of Japan in December 1941, before being retaken by the British at the end of World War II. Shortly before Malaya attained independence from Britain in 1957, George Town was declared a city by Queen Elizabeth II, making it the first city in the country’s modern history. In 1974, the Malaysian federal government revoked George Town’s city status, a position that would not be altered until 2015, when its jurisdiction was reinstated and expanded to cover the entirety of Penang Island and the surrounding islets.

The city is renowned for its unique architectural styles, which have been shaped by centuries of intermingling of various ethnicities and religions. It has also gained a reputation as modern Malaysia’s gastronomical capital for its distinct and ubiquitous street cuisine. The preservation of these cultures contributed to the city centre’s designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2008.

George Town was named in honour of King George III, the ruler of Great Britain and Ireland between 1760 and 1820. Before the arrival of the British, the area had been known as Tanjung Penaga, due to the abundance of penaga laut or Calophyllum inophyllum trees found at the cape or tanjung of the city. It is often mistakenly spelt as Georgetown, which was never the city’s official name. This misspelling may be due to confusion with other places worldwide that share the same name. In common parlance, the city of George Town is also erroneously called Penang, which is the name of the entire state that includes mainland Seberang Perai.

In 1771, Francis Light, a former Royal Navy captain, was instructed by the British East India Company or EIC to establish trade relations in the Malay Peninsula. He arrived in Kedah, a Siamese vassal state facing threats from the Bugis of Selangor. Kedah’s ruler Sultan Muhammad Jiwa Zainal Adilin II offered Light Penang Island in exchange for British military protection. Light noted the strategic potential of the island as a convenient magazine for trade that could enable the British to check Dutch and French territorial ambitions in Southeast Asia, and tried unsuccessfully to persuade his superiors to accept the Sultan’s offer. It was only in 1786 when Light was finally authorised to negotiate the British acquisition of Penang Island. After the cession was finalised with Sultan Abdullah Mukarram Shah of Kedah, Light and his entourage landed on the island on 17 July that year. They took formal possession of the island in the name of King George III of England on 11 August and Penang Island was renamed Prince of Wales Island after the heir to the British throne and the new settlement of George Town – the first of British colonial possessions in Southeast Asia – was established in honour of King George III.

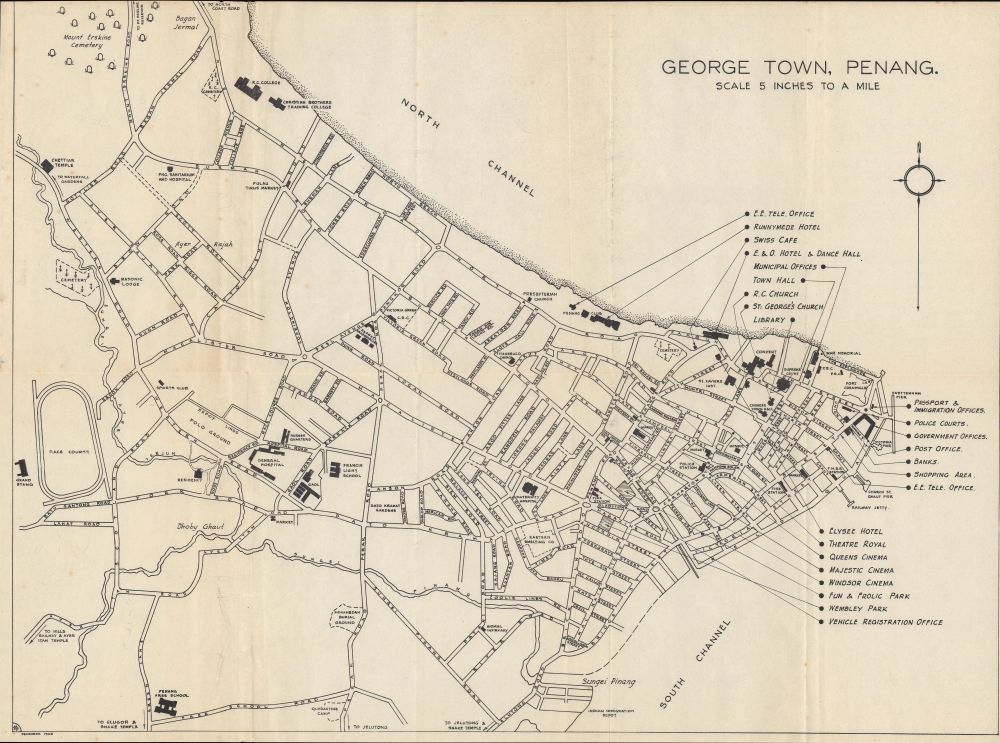

When Light first landed on the cape, it was densely covered in jungle. After the area was cleared, Light instructed the construction of Fort Cornwallis, the first structure in the newly established settlement. Having cleared the jungles at the cape, Light set out to build the first streets of George Town—Light, Beach, Chulia and Pitt streets—that were arranged in a grid-like pattern. As he intended, the new settlement grew rapidly as a free port and a centre of spice production, taking maritime trade from Dutch posts in the region. The spice trade allowed the EIC to cover the administrative costs of Penang. The threat of French invasion amid the Napoleonic Wars forced the British to enlarge and reinforce Fort Cornwallis as the garrison for the settlement.

George Town’s development as the prime British entrepôt along the Malacca Straits led to the establishment of a local government and a Supreme Court in the settlement by 1808, marking the birth of Malaysia’s modern judiciary. In 1826, George Town was made the capital of the Straits Settlements, which was also composed of Singapore and Malacca. However, the capital was then shifted to Singapore in 1832, as the latter had outperformed George Town as the region’s preeminent harbour.

Despite playing second fiddle to Singapore, George Town continued to play a crucial role as a British entrepôt. Following the opening of the Suez Canal and a tin mining boom in the Malay Peninsula, the Port of Penang became a leading exporter of tin. By the end of the 19th century, George Town had become the foremost financial centre of British Malaya, attracting international banks to its shores. Throughout the century, George Town’s population grew rapidly in tandem with the settlement’s economic prosperity. An influx of immigrants from all over Asia quadrupled its population within a mere four decades. A cosmopolitan population emerged, comprising Chinese, Malay, Indian, Peranakan, Eurasian, Thai and other ethnicities. The population growth also created social problems, such as inadequate health facilities and rampant crime, with the latter culminating in the Penang Riots of 1867.

George Town came under direct British rule when the Straits Settlements became a British crown colony in 1867. Law enforcement was beefed up and the secret societies that had previously plagued George Town were gradually outlawed. More investments were also made in the settlement’s health care and public transportation. With improved access to education, a greater level of participation in municipal affairs by its Asian residents and substantial press freedom, George Town was perceived as being more intellectually receptive than Singapore. The settlement became a magnet for English authors, Asian intellectuals and revolutionaries, including Rudyard Kipling, Somerset Maugham and Sun Yat-sen. However, political turmoil in Qing China and the influx of Chinese migrants into the settlement continued to pose security concerns among the British authorities. Sun, in particular, chose George Town as the headquarters for revolutionary activities by the Tongmenghui in Southeast Asia that eventually launched the Wuchang Uprising, a precursor to the Xinhai Revolution that ushered in the beginning of Republican China.

George Town emerged from World War I relatively unscathed, except for the Battle of Penang where the Imperial German Navy cruiser SMS Emden sank two Allied warships off the settlement. This was the only naval battle that took place in Malayan territory during the war. World War II, on the other hand, caused unprecedented social and political turmoil in George Town. In mid-December 1941, the settlement was subjected to severe Japanese aerial bombardment, forcing inhabitants to flee George Town and take refuge in the jungles. While Penang Island had been designated a fortress before the outbreak of fighting, the British high command led by Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival decided to abandon the island and secretly evacuate George Town’s European population, leaving the settlement’s Asian residents at the mercy of the impending Japanese onslaught. Historians have since contended that the moral collapse of British rule in Southeast Asia came not at Singapore, but at Penang.

The Imperial Japanese Army or IJA seized George Town on 19 December without encountering any resistance. During the Japanese occupation, George Town was only lightly garrisoned by the IJA, while the Imperial Japanese Navy converted Swettenham Pier into a major submarine base for the Axis powers. Japanese military police notoriously imposed orders to massacre Chinese civilians under the Sook Ching policy; the victims were buried in mass graves all over the island, such as at Rifle Range, Bukit Dumbar and Batu Ferringhi. Poverty and wanton Japanese brutality towards the local population also forced women into sexual slavery.

Between 1944 and 1945, Allied bombers based in India targeted naval and administrative buildings in George Town, damaging and destroying several colonial buildings in the process. The Penang Strait was mined to constrict Japanese shipping. Following Japan’s surrender, on 3 September 1945, British Royal Marines launched Operation Jurist to retake George Town, making it the first settlement in Malaya to be liberated from the Japanese.

After a period of military administration, the British dissolved the Straits Settlements in 1946 and merged the Crown Colony of Penang into the Malayan Union, which was then replaced with the Federation of Malaya in 1948. At first, the impending annexation of the British colony of Penang into the vast Malay heartland proved unpopular among Penangites. Partly due to concerns that George Town’s free port status would be at risk in the event of Penang’s absorption into Malaya’s customs union, the Penang Secessionist Committee was founded in 1948 and attempted to avert Penang’s merger with Malaya. The secessionist movement was ultimately met with British disapproval. To assuage the concerns raised by the secessionists, the British government guaranteed George Town’s free port status and promised greater decentralisation. Meanwhile, municipal elections were reintroduced in 1951, further diminishing the secessionists’ commitment to their cause. Nine councillors were to be elected from George Town’s three electoral wards, while the British High Commissioner held the power to appoint six more. By 1956, George Town became Malaya’s first fully-elected municipality and in the following year, it was granted city status by Queen Elizabeth II. This made George Town the first city within the Malayan Federation, and by extension, Malaysia.

During the early years of Malaya’s independence, George Town retained its free port status, which had been guaranteed by the British. The George Town City Council enjoyed full financial autonomy and by 1965, it was the wealthiest local government in Malaysia, with an annual revenue almost double that of the Penang state government. This financial strength allowed the Labour-led city government to implement progressive policies, and to take control of George Town’s infrastructure and public transportation. These included the maintenance of its public bus service, as well as the construction of public housing schemes and the Ayer Itam Dam. However, longstanding political differences between the George Town City Council and the Alliance-controlled state government led to allegations of maladministration against the city government. In response, Chief Minister Wong Pow Nee took over the powers of the George Town City Council in 1966. Local government elections nationwide were also suspended in the aftermath of the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation, never to be reinstated.

The period of relative prosperity vis-à-vis the rest of Malaysia came to an end in 1969 when the Malaysian federal government eventually rescinded George Town’s free port status. This sparked massive unemployment, brain drain and urban decay within the city. The federal government also began channelling resources towards the development of Kuala Lumpur and Port Klang, setting the stage for George Town’s protracted decline. To revive Penang’s fortunes, newly-elected Chief Minister Lim Chong Eu launched the Komtar project in 1974 and spearheaded the establishment of the Bayan Lepas Free Industrial Zone or Bayan Lepas FIZ, which, at the time, was outside the city’s periphery. Although these were successful in transforming Penang into a tertiary-based economy, they also led to the decentralisation of the urban population as residents gravitated towards newer suburban townships closer to the Bayan Lepas FIZ. The destruction of hundreds of shophouses and whole streets for the construction of Komtar further exacerbated the hollowing out of George Town.

In 1974, the George Town City Council and the Penang Island Rural District Council were merged to form the Penang Island Municipal Council, which led to a prolonged debate over George Town’s city status. George Town had benefitted from a real estate boom towards the end of the 20th century, but in 2001, the Rent Control Act was repealed, worsening the depopulation of the city’s historical core and leaving colonial-era buildings in disrepair. The city faced additional challenges like incoherent urban planning, poor traffic management and brain drain, lacking the expertise to regulate urban development and arrest its decline. In response, George Town’s civil societies banded together and galvanised public support for the conservation of historic buildings and to restore the city to its former glory. Widespread resentment over the city’s decline also resulted in the then-opposition Pakatan Rakyat bloc, now Pakatan Harapan, wresting power in Penang from the incumbent Barisan Nasional (BN) administration in the 2008 state election.

Efforts to preserve the city’s heritage paid off when in 2008, a portion of George Town was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The newly-elected state government took a more inclusive approach to heritage conservation and sustainable urban development, while concurrently pursuing economic diversification. The city has since witnessed an economic rejuvenation, boosted by an influx of foreign investors and the private sector. Whilst George Town had been declared a city by Queen Elizabeth II in 1957, the city’s jurisdiction was expanded by the Malaysian federal government to encompass the entirety of Penang Island and the surrounding islets in 2015.

The jurisdiction of George Town covers an area of approximately 306 sq km, encompassing the entirety of Penang Island and nine surrounding islets. Over the centuries, the built-up area of George Town has expanded in three directions – along the island’s northern coast, south down the eastern shoreline and towards Penang Hill to the west. The suburb of Balik Pulau is located on the western plains of the island. The surrounding islets within George Town’s jurisdiction are Jerejak, Andaman, Udini, Tikus, Lovers’, Betong, Betong Kecil, Kendi and Rimau Islands.

Penang Hill, with a height of 833 m is the highest point in Penang, serving as a water catchment area and a green lung for George Town. In 2021, the 124.81 sq km Penang Hill Biosphere Reserve was inscribed as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in recognition of the area’s biodiversity. This zone includes the Penang Botanic Gardens and the 25.62 sq km Penang National Park at the northwestern tip of Penang Island, touted as the smallest national park in the world.

Like most island cities, land scarcity is a pressing issue in George Town. Land reclamation projects have been extensively undertaken to provide valuable land in high-demand areas. As of 2015, George Town expanded by 9.5 sq km due to land reclamation that altered much of the city’s eastern shoreline. In 2023, a massive reclamation project commenced off Batu Maung to build the 9.2 sq km Silicon Island, envisioned as a new hub for high-tech manufacturing and commerce. Following years of reclamation, the coastline at Gurney Drive is being transformed into Gurney Bay, earmarked as a new iconic waterfront destination for Penang. Reclamation works to create the nearby mixed-use precinct of Andaman Island are also ongoing.

The Pinang Peranakan Mansion, also known as the Baba and Nonya House or the Blue House, is a two-storey treasure trove of historical antiques and artefacts, making it one of the most unique museums in Malaysia. The iconic green-hued mansion is dedicated to Penang’s Peranakan heritage. The mansion is unique and carefully preserved, where one can see how the old Chinese houses were decorated as well as the customs and traditions they followed. This 19th-century house displays Peranakan relics, antiques, and collections, with a Scottish-European interior.

The Pinang Peranakan Mansion is heavily influenced by both Chinese and European architecture. Upon entering, one sees the wooden panels and open courtyards, which are famous in the Chinese style, which are intermingled with staircases made of material imported specially from Scotland or Victorian centrepieces and figurines that give it its European touch. One can also visit the temple at the side of the house that honours the life and work of Kapitan Cina Chung Keng Kwee, the former owner of the Penang Peranakan Mansion. The Blue Mansion is open daily from 9:30 am to 5 pm with free guided tours available at 11:30 am and 3:30 pm. Entry is free for children under 12 while adults need to pay RM 20 per person.

The Penang War Museum is a former British military fortress that once served as the site for the legendary Battle of Penang against the Japanese army. Situated in Bukit Batu Maung on Penang’s southern coast, it now serves as a museum, gaining fame as Southeast Asia’s largest war museum. It is also dubbed one of Asia’s most haunted sites. This is due to its dark history as a torture house and prison. Many people have claimed to have witnessed paranormal sightings and ghostly apparitions. However, there are varying accounts to this claim. This privately run museum has a lot to explore, including underground tunnels and several historical artefacts like cannons. Although in disuse, most of the structures at the war museum are intact for visitors to wander and explore. There are many underground tunnels, ammunition bunkers, cookhouses and underground offices. Interestingly, some of these tunnels are also linked to the sea. Visitors can check out the barracks where the British, Malay and Indian soldiers used to live and, through old photographs, get an idea of the kind of life the prisoners and the soldiers led there. Also, there are many artefacts on display, including an old bicycle and cannons. Lots of information boards and signs have also been put up.

The Penang War Museum has the defunct former British bastion, built in the 1930s as a defence structure against the sea invasion by the Imperial Japanese Army. However, the unexpected happened and instead, the Japanese launched an aerial attack. The British and Commonwealth troops had no choice but to evacuate the fortress. Thus, it came under the Imperial Japanese Army and was then used as an army base and prison. The Japanese used to interrogate, torture and behead the prisoners here which led to many ghostly stories being linked to it. When the war ended in 1945, the fort fell into disuse. The museum is open daily between 9 am and 7 pm while night tours are conducted between 8 and 10 pm. Reservation is required for night tours and should be booked before 6 pm. Entry fees are RM 30 for adults while children aged between 5 and 12 need to pay RM 15. For optional tours including tunnel tour, canon firing bay, observation tower and tunnel view, additional charges apply ranging from RM 5 to RM 15.