Located in the northernmost part of Borneo, Sabah has land borders with Sarawak to the southwest and Indonesia’s North Kalimantan province to the south. The Federal Territory of Labuan is an island just off Sabah’s west coast. Sabah shares maritime borders with Vietnam to the west and the Philippines to the north and east. Kota Kinabalu is the state capital, the economic centre of the state, and the seat of the Sabah State government. Other major towns in Sabah include Sandakan and Tawau. Sabah has an equatorial climate with tropical rainforests, abundant with animal and plant species. The state has long mountain ranges on the west side, which form part of Crocker Range National Park. The Kinabatangan River, the second longest river in Malaysia, runs through Sabah. The highest point of Sabah, Mount Kinabalu, is also the highest point in Malaysia.

The origin of the name Sabah is uncertain, and many theories have arisen. One theory is that during the time it was part of the Bruneian Sultanate, it was referred to as Saba because of the presence of a variety of banana called pisang saba, also known as pisang menurun, which is grown widely on the coast of the region and popular in Brunei. The Bajau community referred to it as pisang jaba. While the name Saba also refers to a variety of bananas in both Tagalog and Visayan languages, the word in Visayan has the meaning noisy, which in turn is derived from Sanskrit Sabhā, meaning a congregation, or crowd and related to a noisy mob. Due to the local dialect, the word Saba has been pronounced as Sabah by the local community. While Brunei was a vassal state of Majapahit, the Old Javanese eulogy of Nagarakretagama described the area in what is now Sabah as Seludang.

Although the Chinese have been associated with the island since the days of the Han dynasty, they did not have any specific names for the area. Instead, during the Song dynasty, they referred to the whole island as Po Ni, also pronounced Bo N), which is the same name they used to refer to the Sultanate of Brunei at the time. Due to the location of Sabah near Brunei, it has been suggested that Sabah was a Brunei Malay word meaning upstream or in a northerly direction. Another theory suggests that it came from the Malay word sabak, which means a place where palm sugar is extracted. Sabah is also an Arabic word, which means morning.

The presence of multiple theories makes it difficult to pinpoint the true origin of the name. It is nicknamed the Land Below the Wind or Negeri Di Bawah Bayu, as the state lies below the typhoon belt of East Asia and has never been battered by any typhoons, except for several tropical storms.

The earliest known human settlement in the region existed 20,000–30,000 years ago, as evidenced by stone tools and food remains found by excavations along the Darvel Bay area at Madai-Baturong caves near the Tingkayu River. In 2003, archaeologists discovered the Mansuli valley in the Lahad Datu District, which dates back the history of Sabah to 235,000 years. During the 7th century, a settled community known as Vijayapura, a tributary to the Srivijaya empire, was thought to have existed in northwest Borneo. The earliest independent kingdom in Borneo, supposed to have existed in the 9th century, was Po Ni, as recorded in the Chinese geographical treatise Taiping Huanyu Ji. It was believed that Po Ni existed at the mouth of the Brunei River and was the predecessor to the Bruneian Empire.

In the 14th century, Brunei and Sulu were part of the Majapahit Empire but in 1369, Sulu and the other Philippine kingdoms successfully rebelled and Sulu even attacked Brunei, which was still a Majapahit tributary. The Sulus specifically invaded Northeast Borneo at Sabah. The Sulus were repelled but Brunei became weakened. In 1370, Brunei transferred its allegiance to the Ming dynasty of China. The Maharaja Karna of Borneo then paid a visit to Nanjing with his family until his death. He was succeeded by his son, Hsia-wang, who agreed to send tribute to China once every three years. After that, Chinese junks came to northern Borneo with cargoes of spices, bird nests, shark fins, camphor, rattan and pearls. More Chinese traders eventually settled in Kinabatangan, as stated in both Brunei and Sulu records. A younger sister of Ong Sum Ping or Huang Senping, the governor of the Chinese settlement, then married Sultan Ahmad of Brunei. Perhaps due to this relationship, a burial place with 2,000 wooden coffins, some estimated to be 1,000 years old, was discovered in the Agop Batu Tulug Caves and around the Kinabatangan Valley area. It is believed that this type of funeral culture was brought by traders from Mainland China and Indochina to northern Borneo as similar wooden coffins were also discovered in these countries.

During the reign of the fifth sultan of Bolkiah between 1485 and 1524, the Sultanate’s thalassocracy extended over northern Borneo and the Sulu Archipelago, as far as Kota Seludong, present-day Manila, with its influence extending as far as Banjarmasin, taking advantage of maritime trade after the fall of Malacca to the Portuguese. Many Brunei Malays migrated to Sabah during this period, beginning after the Brunei conquest of the territory in the 15th century. But plagued by internal strife, civil war, piracy and the arrival of Western powers, the Bruneian Empire began to shrink. The first Europeans to visit Brunei were the Portuguese, who described the capital of Brunei at the time as surrounded by a stone wall. The Spanish followed, arriving soon after Ferdinand Magellan’s death in 1521, when the remaining members of his expedition sailed to the islands of Balambangan and Banggi in the northern tip of Borneo. Later, in the Castilian War of 1578, the Spanish, who had sailed from New Spain, which was centred in Mexico and had taken Manila from Brunei, unsuccessfully declared war on Brunei by briefly occupying the capital before abandoning it. The Sulu region gained its independence in 1578, forming its sultanate, known as the Sultanate of Sulu.

When the civil war broke out in Brunei between Sultans Abdul Hakkul Mubin and Muhyiddin, the Sulu Sultan asserted their claim to Brunei’s territories in northern Borneo. The Sulus claimed that Sultan Muhyiddin had promised to cede the northern and eastern portions of Borneo to them in compensation for their help in settling the civil war. The territory seems never to have been ceded formally, but the Sulus continued to claim the territory, with Brunei weakened and unable to resist. After the war with the Spanish, the area in northern Borneo began to fall under the influence of the Sulu Sultanate. The seafaring Bajau-Suluk and Illanun people then arrived from the Sulu Archipelago and started settling on the coasts of north and eastern Borneo, fleeing from the oppression of Spanish colonialism. While the thalassocratic Brunei and Sulu sultanates controlled the western and eastern coasts of Sabah, respectively, the interior region remained largely independent from either kingdom. The Sultanate of Bulungan’s influence was limited to the Tawau area, which came under the influence of the Sulu Sultanate before gaining its own rule after the 1878 treaty between the British and Spanish governments.

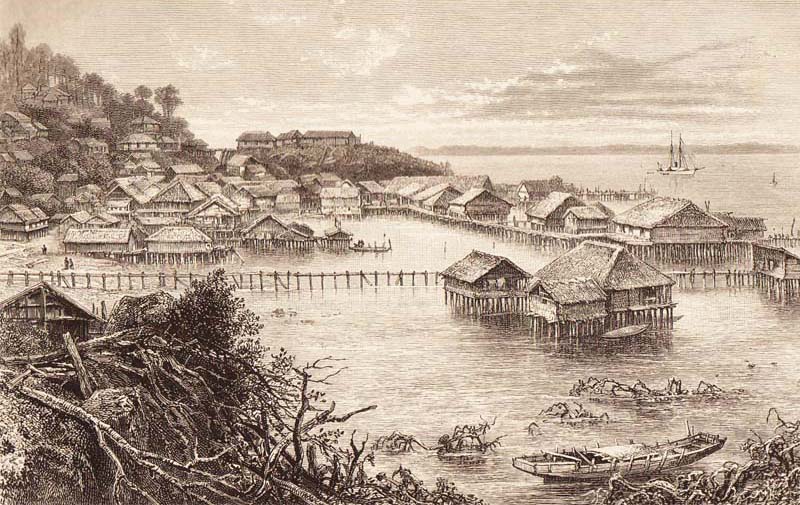

In 1761, Alexander Dalrymple, an officer of the British East India Company, agreed with the Sultan of Sulu to allow him to set up a trading post for the first time in northern Borneo, although this was to prove a failure. Following the British occupation of Manila in 1763, the British freed Sultan Alimuddin from Spanish colonisers and allowed him to return to his throne; this was welcomed by the Sulu people and by 1765, Dalrymple managed to obtain the island, having concluded a Treaty of Alliance and Commerce with the Sultan of Sulu by a willing Sultan Alimuddin as a sign of gratitude for the British aid. A small British factory was then established in 1773 on Balambangan Island, a tiny island situated off the north coast of Borneo. The British saw the island as a suitable location to control the trade route in the East, capable of diverting trade from the Spanish port of Manila and the Dutch port of Batavia, especially with its strategic location between the South China Sea and Sulu Sea. The British abandoned the island two years later when the Sulu pirates began attacking. This forced the British to seek refuge in Brunei in 1774 and to temporarily abandon their attempts to find alternative sites for the factory. Although an attempt was made in 1803 to turn Balambangan into a military station, the British did not re-establish any further trading posts in the region until Stamford Raffles founded Singapore in 1819.

In 1846, the island of Labuan on the west coast of Sabah was ceded to Britain by the Sultan of Brunei through the Treaty of Labuan, and in 1848 it became a British Crown Colony. Seeing the presence of the British in Labuan, the American consul in Brunei, Claude Lee Moses, obtained a ten-year lease in 1865 for a piece of land in northern Borneo. Moses then passed the land to the American Trading Company of Borneo, which chose Kimanis, which they renamed Ellena, and started to build a base there. Requests for financial backing from the US government proved futile and the settlement was later abandoned.

Japanese forces landed in Labuan on January 3, 1942 and later invaded the rest of northern Borneo. From 1942 to 1945, Japanese forces occupied North Borneo, along with most of the rest of the island, as part of the Empire of Japan. The occupation drove many people from coastal towns to the interior, fleeing the Japanese and seeking food. As part of the Borneo Campaign to retake the territory, Allied forces bombed most of the major towns under Japanese control, including Sandakan, which was razed to the ground. The Japanese ran a brutal prisoner-of-war camp known as Sandakan Camp for those siding with the British. The majority of the POWs were British and Australian soldiers captured after the fall of Malaya and Singapore. The prisoners suffered notoriously inhuman conditions, and amidst continuous Allied bombardments, the Japanese forced them to march into Ranau, which is about 260 kilometres away, in an event known as the Sandakan Death March. In March 1945, Australian forces launched Operation Agas to gather intelligence in the region and launch guerrilla warfare against the Japanese. The war ended on September 10, 1945, after the Australian Imperial Forces or AIF succeeded in the battle of North Borneo.

After the Japanese surrender, North Borneo was administered by the British Military Administration and, on July 15, 1946, became a British Crown Colony. The Crown Colony of Labuan was integrated into this new colony. Due to massive destruction in the town of Sandakan since the war, Jesselton was chosen to replace the capital and the Crown continued to rule North Borneo until 1963. Upon Philippine independence in 1946, seven of the British-controlled Turtle Islands, including Cagayan de Tawi-Tawi and Mangsee Islands off the north coast of Borneo, were ceded to the Philippines as part of negotiations between the American and British colonial governments. On August 31, 1963, North Borneo attained self-government. After discussion culminating in the Malaysia Agreement and 20-point agreement, on September 16, 1963, North Borneo as Sabah was united with Malaya, Sarawak and Singapore, to form the independent Malaysia.

From before the formation of Malaysia until 1966, Indonesia adopted a hostile policy towards the British-backed Malaya, leading after the union to the Indonesia-Malaysia confrontation. This undeclared war stemmed from what Indonesian President Sukarno perceived as an expansion of British influence in the region and his intention to wrest control over the whole of Borneo under the Greater Indonesia concept. Meanwhile, the Philippines, beginning with President Diosdado Macapagal on Ju, June 1962, claimed Sabah from cession by heirs of the Sultanate of Sulu. Macapagal, who considered Sabah to be the property of the Sultanate of Sulu, saw the attempt to integrate Sabah, Sarawak and Brunei into the Federation of Malaysia as trying to impose the authority of Malaya on these states.

Sabah held its first state election in 1967. In the same year, the state capital of Jesselton was renamed Kota Kinabalu. On June 14, 1976, the state government of Sabah signed an agreement with Petronas, granting it the right to extract and earn revenue from petroleum found in the territorial waters of Sabah in exchange for 5% in annual revenue as royalties based on the 1974 Petroleum Development Act. The state government of Sabah ceded Labuan to the Malaysian federal government, and Labuan became a federal territory on April 16, 1984. In 2000, the state capital, Kota Kinabalu, was granted city status, making it the 6th city in Malaysia and the first city in the state.

In February 2013, Sabah’s Lahad Datu District was penetrated by followers of Jamalul Kiram III, the self-proclaimed Sultan of the Sulu Sultanate. In response, Malaysian military forces were deployed to the region, following which an Eastern Sabah Security Command was established. Sabah has seen several territorial disputes with Malaysia’s neighbours, Indonesia and the Philippines. In 2002, both Malaysia and Indonesia submitted to arbitration by the ICJ on a territorial dispute over the Ligitan and Sipadan islands, which was later won by Malaysia. There are also several other disputes yet to be settled with Indonesia over the overlapping claims on the Ambalat continental shelf in the Celebes Sea and the land border dispute between Sabah and North Kalimantan. Malaysia’s claim over a portion of the Spratly Islands is also based on sharing a continental shelf with Sabah. The Philippines has a territorial claim over much of the eastern part of Sabah. It claims that the territory is connected with the Sultanate of Sulu and was only leased to the North Borneo Chartered Company in 1878, with the Sultanate’s sovereignty never being relinquished. Malaysia, however, considers this dispute a non-issue, as it interprets the 1878 agreement as that of cession and deems that the residents of Sabah exercised their right to self-determination when they joined to form the Malaysian federation in 1963. Before the 2013 incident, Malaysia continued to dutifully pay an annual cession payment amounting to roughly $1,000 to the indirect heirs of the Sultan, honouring an 1878 agreement, where North Borneo, today’s Sabah, was conceded by the late Sultan of Sulu to a British company. However, the Malaysian government halted payments after this tragedy. As a result, the self-proclaimed Sulu heirs pursued this case for legal arbitration vis-à-vis the original commercial deal. Since then, Sulu claimants have been accused of forum shopping. In 2017, the heirs showed their intention to start arbitration in Spain and asked for $32.2 billion in compensation. In 2019, Malaysia responded for the first time. The attorney general at the time offered to start making yearly payments again and to pay RM 48,000 or about USD 10,400 for past dues and interest, but only if the heirs gave up their claim. The heirs did not accept this offer and the case, led by Spanish arbiter Gonzalo Stampa, continued without Malaysia being involved. In February 2022, Gonzalo Stampa awarded US$14.9 billion to the Sultan of Sulu’s heirs, who have since sought to enforce the award against Malaysian state-owned assets around the world. It is noteworthy that on 27 June 2023, the Hague Court of Appeal dismissed the Sulus’ bid and ruled in favour of the Malaysian government, which hailed the decision as a landmark victory.

The Philippine claim can be based on three historical events: the Brunei Civil War from 1660 until 1673, the treaty between the Dutch East Indies and the Bulungan Sultanate in 1850 and the treaty between Sultan Jamal ul-Azam and Overbeck in 1878. Further attempts by several Filipino politicians to destabilise Sabah proved to be futile and led to the Jabidah massacre in Corregidor Island, Philippines. This led the Malaysian government to support the insurgency in the southern Philippines. Although the Philippine claim to Sabah has not been actively pursued for some years, some Filipino politicians have promised to bring it up again, while the Malaysian government has asked the Philippines not to threaten ties over such an issue.

Sabah exhibits notable diversity in ethnicity, culture and language. It is known for its traditional musical instrument, the sompoton. Sabah has abundant natural resources, and its economy is strongly export-oriented. Its primary exports include oil, gas, timber and palm oil. The other major industries are agriculture and ecotourism. Sabah is located south of the typhoon belt, making it insusceptible to the devastating effects of the typhoons that frequently batter the neighbouring Philippines. The state is surrounded by the South China Sea in the west, the Sulu Sea in the northeast and the Celebes Sea in the southeast. Sabah’s 1,743 km of coastline faces erosion and because it is surrounded by three seas, it has extensive marine resources. The state coastline is covered with mangrove and nipah forests. Both coastal areas on the west coast and east coast are entirely dominated by sand beaches, while in sheltered areas the sand is mixed with mud. The western part of Sabah is generally mountainous, containing three of the highest peaks. The main mountain range is the Crocker Range, with several mountains of varying heights. Adjacent to the Crocker Range is the Trus Madi Range, with Mount Trus Madi, at a height of 2,642 m. The highest peak is Mount Kinabalu, at a height of 4,095 m. The central and eastern portions of Sabah are generally lower mountain ranges and plains with occasional hills. On the east coast is the Kinabatangan River, which is the second-longest river in Malaysia after the Rajang River in Sarawak, with a length of 560 km. Sabah experiences two monsoon seasons, the northeast and southwest. It also receives two inter-monsoon seasons, from April to May and September to October. As Sabah lies within the Sunda Plate with compression from the Australian and Philippine Plates, it is prone to earthquakes.

The kingfisher is the state bird of Sabah and is featured in one of its coats of arms. The Semporna Peninsula on the north-eastern coast of Sabah is identified as a hotspot of high marine biodiversity importance in the Coral Triangle. The jungles of Sabah host a diverse array of plant and animal species. Most of Sabah’s biodiversity is located in the forest reserve areas, which form half of its total landmass. Its forest reserves are part of the 20 million hectares of equatorial rainforests demarcated under the Heart of Borneo initiative. Kinabalu National Park was inscribed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2000 for its richness in plant diversity combined with its unique geological, topographical, and climatic conditions. The park hosts more than 4,500 species of flora and fauna, including 326 birds and around 100 mammal species, along with over 110 land snail species.

Since the post-World War II timber boom, driven by the need for raw materials from industrial countries, Sabah forests have been gradually eroded by uncontrolled timber exploitation and the conversion of Sabah forest lands into palm oil plantations. Since 1970, the forestry sector has contributed to over 50% of the state revenue, of which a study conducted in 1997 revealed the state had almost depleted all of its virgin forests outside the conservation areas.