Today’s topic is not exactly a festival which is celebrated in India, but given that it is the birth anniversary of the man who is credited with consolidating the Advaita Vedanta doctrine and reviving it at a time when Sanatana Dharma or Hindusim and the Hindu culture was on a decline, I thought it is something we all, but especially practicing Hindus should celebrate, even if it is as a small private prayer.

Yesterday was the 1232nd birth anniversary of Adi Shankaracharya, who is credited with consolidating the doctrine of Advaita Vedanta and with unifying and establishing the main currents of thought in Hinduism. You could call him the founder of the religion, but that’s not entirely right as Hinduism is more a way of life rather than an organised religion and has been around for centuries before him. Adi Shankaracharya Jayanti is observed on Panchami Tithi during Shukla Paksha of Vaishakha month which falls between April and May each year.

While there is no really consensus on where and when he was born, most scholars and historians agree as do the oldest biographies written about him, that he was born in what is today the southern Indian state of Kerala, in a village named Kaladi which is sometimes spelt as Kalady, Kalati or Karati to Nambudiri Brahmin parents in 788. His parents, Shivaguru and Aryamba, were an aged, childless, couple who led a devout life of service to the poor. They named their child Shankara, meaning “giver of prosperity”. A legend associated with Adi Shankaracharya considers him an incarnation of Lord Shiva himself, who had appeared in Aryamba’s dream and promised to take birth as her child. This could also be the reason for his name, which is one of the names of Lord Shiva. His father died while Shankara was very young and so his upanayanam or thread ceremony, the initiation into student-life, had to be delayed due to the death of his father, and was then performed by his mother. He was someone who was attracted to the life of Sannyasa or being a hermit from early childhood which his mother naturally disapproved.

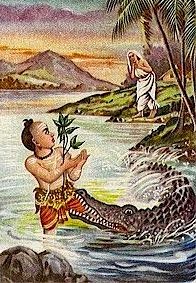

A story, found in all biographies, describe Shankara at age eight going to a river with his mother, Sivataraka, to bathe, and where he is caught by a crocodile. Shankara called out to his mother to give him permission to become a Sannyasin or else the crocodile will kill him. The mother agrees, Shankara is freed and leaves his home for education. He reaches a Saivite sanctuary along a river in a north-central state of India, and becomes the disciple of a teacher named Govinda Bhagavatpada. The various stories about him then diverge in the details about the first meeting between Shankara and his Guru, where they met, as well as what happened later. Several texts suggest Shankara’s schooling with Govindapada happened along the river Narmada in Omkareshwar, in present day Madhya Pradesh, which a few place it along river Ganges in Kashi or Varanasi as well as Badari which is now Badrinath up in the Himalayas in present day Uttarakhand. It is said that Lord Vishnu visited Shankara at Badrinath and asked him to make a statue of the deity on the Alaknanda River. Today, this temple is popular as the Badrinarayan Temple.

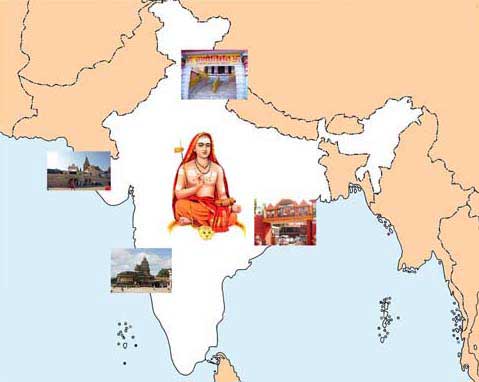

The biographies vary in their description of where he went, who he met and debated and many other details of his life. Most mention Shankara studying the Vedas, Upanishads and Brahmasutra with Govindapada, and Shankara authoring several key works in his youth, while he was studying with his teacher. It is with his teacher Govinda, that Shankara studied Gaudapadiya Karika, as Govinda was himself taught by Gaudapada. Most also mention a meeting with scholars of the Mimamsa school of Hinduism namely Kumarila and Prabhakara, as well as Mandana and various Buddhists, in Shastrarth which is an Indian tradition of public philosophical debates attended by large number of people and sometimes with royalty. After this, the biographies about Shankara vary significantly. Different and widely inconsistent accounts of his life include diverse journeys, pilgrimages, public debates, installation of yantras and lingas, as well as the founding of monastic centers in north, east, west and south India. Most biographies mention that Shankara traveled widely within India, from Gujarat to Bengal and from Tamil Nadu to Kashmir and participating in public philosophical debates with different orthodox schools of Hindu philosophy, as well as heterodox traditions such as Buddhists, Jains, Arhatas, Saugatas, and Carvakas. During his tours, he is credited with starting several Matha or monasteries and ten monastic orders in different parts of India are generally attributed to Shankara’s travel-inspired Sannyasin schools, each with Advaita notions, of which four have continued in his tradition: Bharati in Sringeri, Karnataka, Saraswati in Kanchipuram, Tamil Nadu and Tirtha and Asramin in Dwarka, Gujarat. Other monasteries that record Shankara’s visit include Giri, Puri, Vana, Aranya, Parvata and Sagara – all names traceable to Ashrama system in Hinduism and Vedic literature.

Adi Shankara’s works are the foundation of Advaita Vedanta school of Hinduism and his masterpiece of commentary is the Brahmasutrabhasya which is literally, the commentary on the Brahma Sutra, a fundamental text of the Vedanta school of Hinduism. The term Advaita refers to its idea that the true self, Atman, is the same as the highest metaphysical reality of the universe, Brahman. Advaita Vedanta is the oldest extant sub-school of Vedanta, which is one of the six orthodox or astika Hindu philosophies or darsanas tracing its roots back to the first century BC.

The word Advaita is a composite of two Sanskrit words – the prefix “A” which has similar meaning of english prefix “Non” and “Dvaita” which means ‘Duality’ or ‘Dualism’. The word Vedanta is a compostion of the two Sanskrit words, the word Veda referring to the whole corpus of vedic texts, and the other word “Anta” meaning ‘End’. The meaning of Vedanta can be summed up as “the end of the vedas” or “the ultimate knowledge of the vedas”.

Adi Shankarachrya has an unparallelled status in the tradition of Advaita Vedanta. He travelled all over India to help restore the study of the Vedas. His teachings and tradition form the basis of Smartism and have influenced Sant Mat lineages. He introduced the Pancayatana form of worship, which is the simultaneous worship of five deities – Ganesha, Surya, Vishnu, Shiva and Devi. Adi Shankaracharya explained that all deities were but different forms of the one Brahman, the invisible Supreme Being.

Adi Shankara is regarded as the founder of the Dasanami Sampradaya of Hindu monasticism and Ṣaṇmata of the Smarta tradition. He unified the theistic sects into a common framework of Shanmata system. Advaita Vedanta is, at least in the west, primarily known as a philosophical system. But it is also a tradition of renunciation.

Adi Sankarachatya organised the Hindu monks of these ten sects or Dasanami Sampradaya under four Maṭhas or monasteries, one in each direction in India with the headquarters at Dwaraka. Gujarat west, Jagannatha Puri in Odisha in the east, Sringeri in Karnataka in the south and Badrikashrama or as it’s called today, Badrinath in Uttarakhand in the north. Each math was headed by one of his four main disciples, who each continue the Vedanta Sampradaya. The mathas which he built exist until today, and preserve the teachings and influence of Shankara. My family is follows the advaita form of Hindusim and I have written about the Sringeri Sarada Peetham Matha which we follow. We also follow the Yajur veda philosophy, which I think a majority of at least Tamil Brahmins follow (there are exceptions) which is falls under the Sringeri Sarada Peetham.

Despite historical links with Shaivism, advaita is not a Shaiva sect, instead advaitins are non-sectarian, and they advocate worship of the Lords Shiva and Vishnu equally with that of the other deities of Hinduism, like Shakti, Ganapati and others.

Adi Sankara is commonly believed to have died aged 32, at Kedarnath in the northern Indian state of Uttarakhand, in the foothills of the Himalayas in 820. Texts say that he was last seen by his disciples behind the Kedarnath temple, walking in the Himalayas until he was not traced. Some texts locate his death in alternate locations such as Kanchipuram in Tamil Nadu and somewhere in his home state of Kerala.