Also known as Namsoong, Losoong is one of Sikkim’s most significant and vibrant celebrations. This joyous festival marks the beginning of the Sikkimese New Year and commemorates the end of the harvest season. Beyond its agricultural significance, Losoong has evolved into a grand cultural showcase, highlighting the unique traditions and heritage of Sikkim.

The roots of Losoong can be traced back to the agrarian lifestyle that has long been the backbone of Sikkimese society. Initially, the festival was primarily celebrated by the Bhutia community, one of the major ethnic groups in Sikkim. However, over time, Losoong has transcended its original cultural boundaries and is now embraced by various communities in the region.

The festival’s expansion reflects the cultural diversity and integration that characterizes Sikkim. Today, Losoong is celebrated not only by the Bhutias but also by the Lepchas and other smaller tribes across Sikkim, Darjeeling, and even parts of Nepal. This widespread adoption of the festival speaks to its universal themes of gratitude, renewal, and community celebration.

The evolution of Losoong from a community-specific celebration to a widely observed festival also mirrors the historical changes in Sikkim. As the region saw increased interaction and cultural exchange between different communities, festivals like Losoong became platforms for shared celebration and cultural expression.

Losoong’s timing is intricately linked to the Tibetan Lunar Calendar, typically falling on the 18th day of the 10th lunar month. In the Gregorian calendar, this usually corresponds to a date in December. The festival’s alignment with the lunar calendar underscores its connection to natural cycles and agricultural rhythms, which have long guided the lives of Sikkimese people.

The celebration of Losoong is not confined to a single day but extends over four days. This extended duration allows for a rich tapestry of events, rituals, and festivities to unfold. The multi-day celebration also reflects the importance of the festival in Sikkimese culture, providing ample time for both religious observances and communal festivities.

During these four days, the entire region of Sikkim comes alive with a festive atmosphere. Streets are adorned with colourful flags and decorations, creating a striking contrast against the backdrop of snow-capped mountains. Monasteries and monks prepare for elaborate celebrations, while local communities organize various events and competitions.

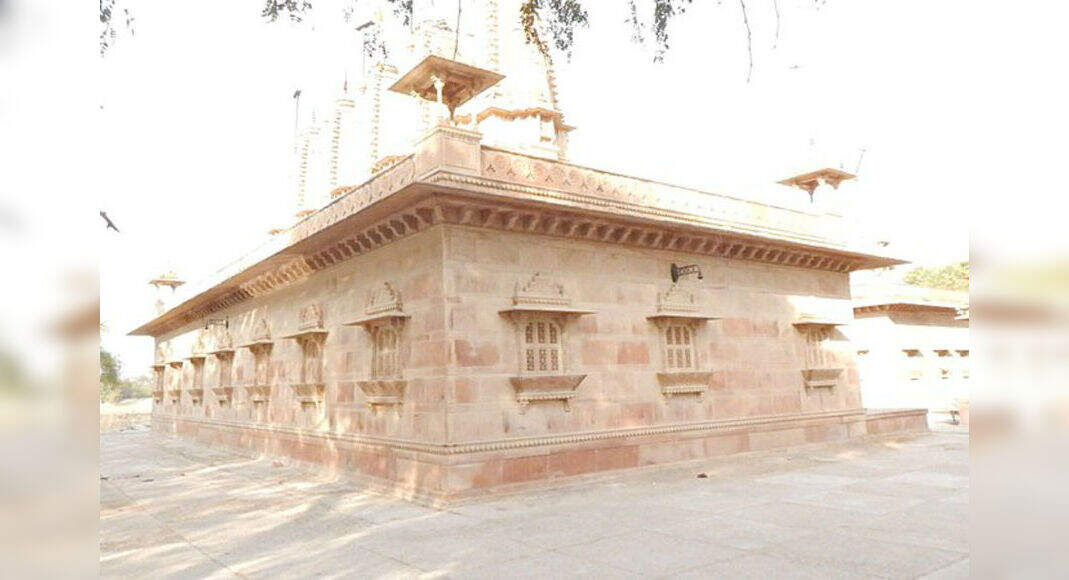

The festival serves as a platform for showcasing traditional folk dances, religious rituals, and ceremonies that have been passed down through generations. At the heart of the cultural celebrations are the ancient monasteries of Sikkim, particularly the renowned Rumtek Monastery and Tsuklakhang Palace. These sacred spaces become focal points for cultural events, hosting a variety of performances that bring together the spiritual and artistic elements of Sikkimese culture.

One of the most captivating aspects of Losoong is the performance of traditional dances. These dances are not merely entertainment but serve as living repositories of Sikkimese history, mythology, and cultural values. Each movement and gesture in these dances carries deep symbolic meaning, often narrating stories of historical events, spiritual beliefs, or moral teachings.

Among the various dance performances, the Black Hat dance holds a special place in the Losoong celebrations. This dance is a powerful reminder to the locals of the eternal victory of good over evil. Through its intricate choreography and symbolic costumes, the Black Hat dance encapsulates key elements of Sikkimese spiritual beliefs and historical narratives.

The festival also provides a platform for local artisans, musicians, and performers to showcase their talents. This not only helps in preserving traditional art forms but also allows for their evolution and adaptation in contemporary contexts. The coming together of various artistic expressions during Losoong creates a rich, multifaceted cultural experience that reflects the diversity and creativity of Sikkimese society.

The rituals and ceremonies of Losoong are deeply rooted in Sikkimese spiritual traditions, many of which share close ties with Tibetan Buddhist practices. This connection is evident in the similarities between Losoong and Losar, the Tibetan New Year celebration. The proximity of Sikkim to Tibet has led to a natural assimilation of many Tibetan rituals and customs into Sikkimese culture.

One of the most significant and visually striking rituals of Losoong is the performance of Cham dances by Buddhist monks. These sacred dances are not merely performances but are considered a form of meditation in motion and a means of spiritual teaching. The dancers, adorned in elaborate costumes and masks, perform precise movements that symbolize various aspects of Buddhist philosophy and mythology.

The Cham dances are characterised by their vibrant colours, intricate masks, and the rhythmic accompaniment of traditional music. Each dance tells a specific story or represents a particular deity or concept from Buddhist teachings. The masks worn by the dancers are particularly significant, often depicting various deities, demons, or animals, each with its symbolic meaning.

Another important ritual is the offering of Chi-Fut to the deities. Chi-Fut is a type of locally brewed alcohol that holds special significance in Sikkimese culture. The offering of Chi-Fut is believed to please the deities and seek their blessings for the coming year. This ritual underscores the blend of spiritual practices and local traditions that characterize Losoong celebrations.

A key symbolic ritual during Losoong is the burning of an effigy representing a demon king. This act symbolizes the destruction of evil forces and the purification of the community as it enters the new year. The ritual burning is often accompanied by prayers and chants, creating a powerful atmosphere of spiritual renewal.

Archery contests are another integral part of Losoong celebrations. These competitions not only showcase the traditional skills valued in Sikkimese culture but also serve as a form of community bonding and friendly competition. The archery contests often draw large crowds and are accompanied by cheering, music, and a festive atmosphere.

Throughout the festival, monasteries play a crucial role in conducting various religious ceremonies. Monks engage in extended prayer sessions and perform rituals aimed at blessing the community and warding off misfortunes for the coming year. These religious observances provide a spiritual foundation to the festivities, reminding participants of the deeper meanings behind the celebrations.

Losoong holds profound religious significance, deeply rooted in the spiritual beliefs and practices of Sikkim. The festival is not merely a cultural celebration but a time of spiritual renewal and rededication for the Sikkimese people. Central to the religious aspect of Losoong is the belief in the power of ritual and prayer to cleanse negative energies and invite positive forces for the new year. The various ceremonies conducted during the festival are believed to eliminate bad luck and misfortunes. Monks play a crucial role in this spiritual cleansing, conducting rigorous rituals and ceremonies to seek blessings from gods and goddesses for the upcoming year.

The religious aspects of Losoong also reflect the syncretic nature of Sikkimese spirituality, which blends elements of Buddhism, Hinduism, and indigenous beliefs. This spiritual diversity is evident in the various rituals and practices observed during the festival, each contributing to a rich tapestry of religious expression.

The spiritual significance of Losoong extends beyond the formal rituals. It is seen as a time for personal reflection and renewal, where individuals can reflect on the past year and set intentions for the new one. This personal spiritual dimension adds depth to the communal celebrations, making Losoong a holistic experience that addresses both individual and collective spiritual needs.

No celebration in Sikkim is complete without indulging in the local cuisine, and Losoong is no exception. The festival provides a perfect opportunity to showcase the rich culinary heritage of Sikkim, with a wide array of traditional dishes prepared and shared during the celebrations. Some of the traditional dishes consumed during Losoong include Aalum, a traditional Sikkimese dish made from boiled potatoes mixed with spices and herbs, Babar which is a type of bread made from fermented rice batter, often served as a staple during festive meals, Furaula, a sweet dish made from rice flour, often shaped into various forms and deep-fried, and Gundruk, a fermented leafy green vegetable, considered a delicacy in Sikkimese cuisine.

In addition to these traditional dishes, Losoong also sees the preparation of special festive foods. Families often prepare elaborate meals to share with relatives and friends, fostering a sense of community and hospitality. The communal sharing of food during Losoong is seen as a way of strengthening social bonds and expressing gratitude for the abundance of the harvest.

Beverages also play an important role in Losoong celebrations. Traditional drinks like Chang, a millet-based alcoholic beverage, are often consumed during the festivities. These drinks are not just refreshments but are often imbued with cultural and sometimes spiritual significance.

Losoong’s impact extends far beyond its religious and cultural significance, playing a crucial role in the social fabric of Sikkimese society. The festival serves multiple important functions in the community. Losoong brings together people from various backgrounds, strengthening social ties within the community. The shared experiences of celebration, ritual, and feasting create a sense of unity and belonging among participants. Through its rituals, dances, and customs, Losoong plays a vital role in preserving and transmitting Sikkimese cultural heritage. It provides a platform for younger generations to learn about and engage with traditional practices.

The festival attracts tourists and visitors, providing an economic boost to local businesses. Artisans, performers, and food vendors often find increased opportunities during the festival period. As a festival celebrated by various ethnic groups, Losoong fosters inter-community understanding and harmony. It serves as a reminder of the shared cultural heritage that unites different communities in Sikkim. For the Sikkimese people, Losoong is an important marker of cultural identity. It allows them to celebrate their unique heritage and affirm their place in the diverse cultural landscape of India. The festival serves as an important marker in the agricultural and social calendar of Sikkim, helping to structure the year’s activities and providing a sense of cyclical renewal.

While Losoong itself is not associated with a specific mythological story, it is deeply connected to the broader mythological and spiritual beliefs of Sikkim. These beliefs, which blend Buddhist, Hindu, and indigenous elements, provide a rich backdrop to the festival celebrations. One of the key mythological elements reflected in Losoong is the concept of cosmic renewal. Many of the rituals and practices during the festival symbolize the cyclical nature of time and the eternal struggle between good and evil. The burning of the effigy of the demon king, for instance, represents the triumph of positive forces over negative ones, a theme common in many mythological narratives.

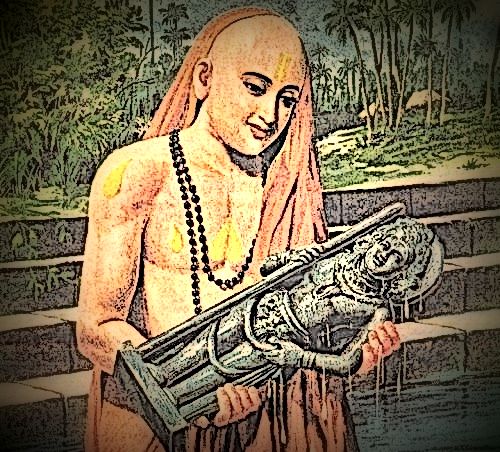

The Black Hat dance, performed during Losoong, is steeped in legend. According to some accounts, this dance commemorates the assassination of King Langdarma, a 9th-century Tibetan king who was opposed to Buddhism. The dance is said to reenact how a Buddhist monk, disguised as a Cham dancer, assassinated the king to protect the dharma.

Another mythological element present in Losoong celebrations is the worship of local deities and nature spirits. Sikkim’s indigenous beliefs include a pantheon of local gods and spirits associated with mountains, rivers, and forests. During Losoong, offerings and prayers are often made to these entities, reflecting the deep connection between the Sikkimese people and their natural environment. The concept of karma and its cyclical nature is also reflected in many Losoong rituals. The idea that actions in one year can influence the fortunes of the next is a driving force behind many of the purification and blessing ceremonies conducted during the festival.

While not directly related to Losoong, the legend of Guru Padmasambhava, who is said to have introduced Buddhism to Sikkim, forms an important part of the spiritual backdrop against which the festival is celebrated. Many of the monasteries that play a central role in Losoong celebrations trace their spiritual lineage back to Guru Padmasambhava. These myths and legends, while not always explicitly narrated during Losoong, form the spiritual and cultural foundation upon which the festival is built. They provide depth and meaning to the various rituals and practices, connecting the present-day celebrations to a rich tapestry of historical and spiritual narratives.

While Losoong continues to be a vibrant and significant festival in Sikkim, it faces several challenges in the modern era. As more young people move to cities for education and employment, there’s a risk of losing connection with traditional practices. The influence of global popular culture can sometimes overshadow traditional cultural expressions. There’s a delicate balance between promoting the festival for tourism and maintaining its authentic cultural significance. The increased footfall during the festival period can put pressure on local ecosystems, especially in ecologically sensitive areas. As farming methods modernize and change, there’s a risk of losing the deep connection between the festival and traditional agricultural cycles.

In response to these challenges, various preservation efforts are underway. Efforts are being made to document the rituals, songs, and dances associated with Losoong to ensure their preservation for future generations. Schools and cultural organizations in Sikkim are working to educate younger generations about the significance of Losoong and other traditional festivals. The Sikkim government has recognized the importance of preserving cultural heritage and provides support for traditional festivals like Losoong. Local communities are taking active roles in organizing and promoting Losoong celebrations, ensuring that the festival remains relevant and meaningful. Efforts are being made to promote responsible tourism during Losoong, balancing economic benefits with cultural and environmental preservation. While maintaining core traditions, there’s also an effort to adapt certain aspects of the festival to make them more relevant and engaging for younger generations.

In the 21st century, Losoong has evolved to meet the changing needs and contexts of Sikkimese society while still maintaining its core cultural significance. The festival now serves multiple roles. Losoong has become a showcase of Sikkimese culture for visitors from other parts of India and abroad, helping to promote cultural tourism in the state. In an era of rapid social change, Losoong provides an important anchor for community identity and cohesion. The festival’s agricultural roots are being leveraged to promote awareness about sustainable farming practices and environmental conservation. As a festival celebrated by people of different faiths, Losoong serves as a model for interfaith harmony and cultural integration. The festival period provides economic opportunities for local artisans, performers, and small businesses. For the younger generation of Sikkimese, Losoong serves as an immersive educational experience in their cultural heritage.

Losoong, the Sikkimese New Year festival, is a vibrant testament to the rich cultural heritage of Sikkim. From its origins as an agricultural celebration to its current status as a major cultural event, Losoong has evolved while maintaining its core essence of community,