Viswakarma Jayanti is a significant festival in India, dedicated to Lord Vishwakarma, the divine architect and craftsman of the gods. The festival honours the contributions of artisans, craftsmen, and engineers who play a crucial role in shaping the world around us.

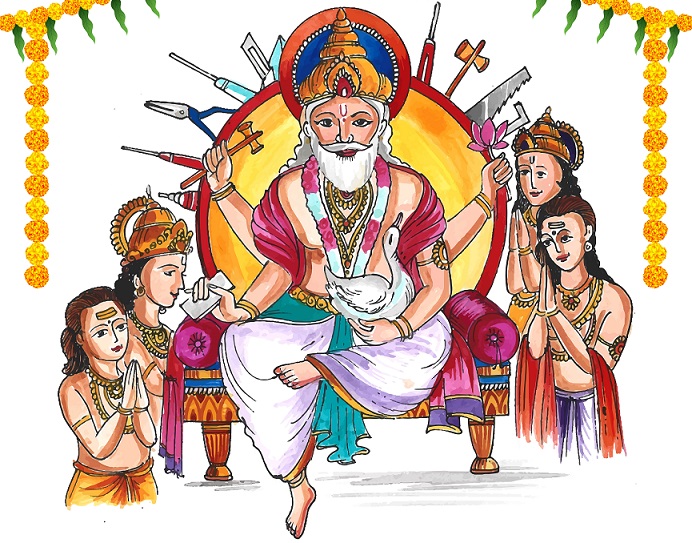

Lord Vishwakarma is a prominent figure in Hindu mythology, revered as the divine architect and craftsman of the gods. He is often depicted as a deity with multiple arms, holding various tools and instruments associated with construction and craftsmanship. According to Hindu scriptures, Vishwakarma is credited with designing and building some of the most magnificent structures in the universe, including the palaces of the gods, celestial weapons, and even entire cities.

Vishwakarma is believed to be the son of Lord Brahma, the creator of the universe. As the divine architect, Vishwakarma inherited his father’s creative abilities and was bestowed with the responsibility of designing and constructing the physical world. He is often associated with the Rigveda, one of the oldest sacred texts in Hinduism, where he is described as the divine carpenter and the all-seeing god.

Throughout Hindu mythology, Vishwakarma is credited with numerous architectural marvels and inventions. Some of his most notable creations include Swarga Loka which is the heavenly abode of Lord Indra, the king of the gods. Swarga Loka is described as a magnificent palace adorned with precious gems and surrounded by lush gardens. Vishwakarma is believed to have constructed the Pushpaka Vimana, a flying chariot used by the gods. This celestial vehicle is often mentioned in ancient texts and is considered a symbol of advanced engineering and craftsmanship. The legendary city of Dwaraka, the capital of Lord Krishna’s kingdom, is said to have been built by Vishwakarma. The city was renowned for its grandeur and architectural brilliance. The capital city of the Pandavas in the epic Mahabharata, Indraprastha, was also designed by Vishwakarma. The city was known for its opulent palaces, intricate designs, and advanced infrastructure.

Viswakarma Jayanti is celebrated to honour the contributions of Lord Vishwakarma and to seek his blessings for success and prosperity in various fields of craftsmanship and engineering. The festival holds special significance for artisans, craftsmen, engineers, architects, and industrial workers, who consider Vishwakarma as their patron deity. The festival is typically celebrated on the last day of the Bengali month of Bhadra, which usually falls in mid-September. This day is also known as Kanya Sankranti or Bhadra Sankranti. In some regions, the festival is observed on the day following Diwali, the festival of lights.

Viswakarma Jayanti is celebrated with great enthusiasm and devotion across India. The celebrations vary from region to region, but some common practices and rituals are observed universally. On Viswakarma Jayanti, devotees set up altars and idols of Lord Vishwakarma in their homes, workshops, and factories. The idols are adorned with flowers, garlands, and other decorations. Special prayers and rituals are performed to invoke the blessings of the divine architect. Devotees offer fruits, sweets, and other delicacies to the deity as a mark of respect and gratitude.

One of the unique aspects of Viswakarma Jayanti is the worship of tools, machinery, and instruments used in various trades and professions. Artisans, craftsmen, and industrial workers clean and decorate their tools and equipment, and perform rituals to seek the blessings of Vishwakarma for their smooth functioning and success in their work. This practice symbolises the importance of tools and machinery in the creation and sustenance of the physical world.

In many regions, community feasts and gatherings are organised to celebrate Viswakarma Jayanti. People come together to share meals, exchange greetings, and participate in cultural programs and activities. These gatherings foster a sense of camaraderie and unity among the community members.

In some parts of India, particularly in the eastern states of West Bengal, Odisha, and Assam, flying kites is a popular tradition on Viswakarma Jayanti. The skies are filled with colourful kites of various shapes and sizes, symbolizing the spirit of freedom and creativity.

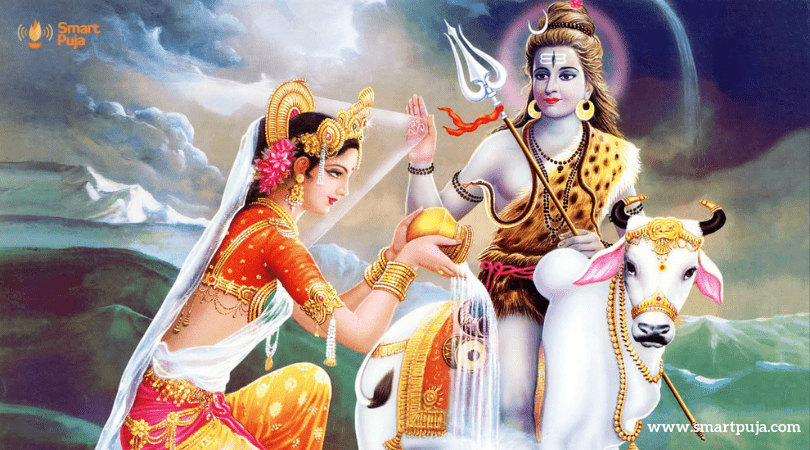

Viswakarma Jayanti is steeped in rich mythology and folklore, with numerous stories and legends associated with Lord Vishwakarma and his divine creations. One of the most famous stories associated with Vishwakarma is the creation of the golden city of Lanka. According to Hindu mythology, Vishwakarma built the city of Lanka for Lord Shiva. The city was made entirely of gold and was known for its unparalleled beauty and grandeur. However, Lord Shiva later gifted the city to the demon king Ravana as a reward for his devotion and penance. Lanka became the capital of Ravana’s kingdom and played a central role in the epic Ramayana.

The Sudarshana Chakra, a powerful weapon wielded by Lord Vishnu, is believed to have been crafted by Vishwakarma. According to legend, Vishwakarma created the Sudarshana Chakra using the dust from the sun’s rays. The weapon is known for its incredible speed and precision, and it is said to have the ability to destroy any enemy.

Another interesting story revolves around the birth of Vishwakarma’s daughter, Sanjana. According to mythology, Sanjana was married to Surya, the sun god. However, unable to bear the intense heat and radiance of her husband, Sanjana created a shadow of herself, known as Chhaya, and left her in her place while she went to her father’s house. When Surya discovered the deception, he sought Vishwakarma’s help to reduce his heat and radiance. Vishwakarma agreed and used his divine skills to trim Surya’s radiance, making it bearable for Sanjana to return to her husband.

Viswakarma Jayanti is celebrated with great enthusiasm in various parts of India, each region adding its unique cultural flavour to the festivities. In West Bengal, Viswakarma Jayanti is a major festival, especially among the working class, artisans, and industrial workers. The festival is marked by elaborate rituals, community feasts, and cultural programs. Factories, workshops, and offices are decorated with flowers and lights, and special prayers are offered to Lord Vishwakarma. The tradition of flying kites is also a significant part of the celebrations in this region.

In Odisha, Viswakarma Jayanti is celebrated with great devotion and enthusiasm. Artisans and craftsmen worship their tools and machinery, seeking the blessings of Vishwakarma for success and prosperity in their work. Special rituals and prayers are performed in temples and homes, and community feasts are organized to mark the occasion.

In Karnataka, Viswakarma Jayanti is celebrated particularly among the Vishwakarma community, which comprises artisans, craftsmen, and engineers. The festival is marked by the worship of tools and machinery, special prayers, and community gatherings. Cultural programs and activities are organised to celebrate the contributions of the Vishwakarma community to society.

In Tamil Nadu, Viswakarma Jayanti is celebrated particularly among industrial workers and artisans. Special prayers and rituals are performed in factories, workshops, and homes to seek the blessings of Lord Vishwakarma. The festival is also marked by community feasts and cultural programs, fostering a sense of unity and camaraderie among the people.

In today’s fast-paced and technologically advanced world, the celebration of Viswakarma Jayanti holds significant relevance. The festival serves as a reminder of the importance of craftsmanship, creativity, and innovation in shaping the world around us. It honours the contributions of artisans, craftsmen, engineers, and industrial workers, who play a crucial role in the development and progress of society.

Viswakarma Jayanti highlights the importance of skill development and innovation in various fields of craftsmanship and engineering. The festival encourages individuals to hone their skills, embrace creativity, and strive for excellence in their respective trades and professions. It also serves as an inspiration for the younger generation to pursue careers in craftsmanship and engineering, contributing to the growth and development of the nation.

For the Vishwakarma community, celebrating Viswakarma Jayanti fosters a sense of pride and identity. The festival provides an opportunity for the community to come together, celebrate their heritage, and honour their patron deity. It also serves as a platform to showcase their skills, talents, and contributions to society.

The worship of tools and machinery during Viswakarma Jayanti also emphasises the importance of environmental sustainability. By seeking the blessings of Vishwakarma for the smooth functioning of their tools and equipment, individuals are reminded of the need to use resources responsibly and sustainably. The festival encourages the adoption of eco-friendly practices and technologies in various fields of craftsmanship and engineering.

Viswakarma Jayanti is a celebration of creativity, craftsmanship, and innovation. It honours the contributions of Lord Vishwakarma, the divine architect, and the countless artisans, craftsmen, and engineers who shape the world around us. The festival is marked by elaborate rituals, community gatherings, and cultural programs, fostering a sense of unity and pride among the people.