Commemorating the birth anniversary of Sri Madhvacharya, one of India’s most influential philosophers and theologians, Madhvacharya Jayanti typically falls in September or October according to the Gregorian calendar, marks the birth of a man who profoundly impacted Hindu philosophy and continues to inspire millions of followers worldwide.

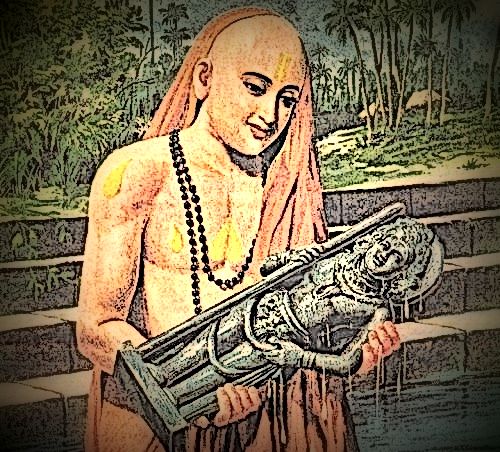

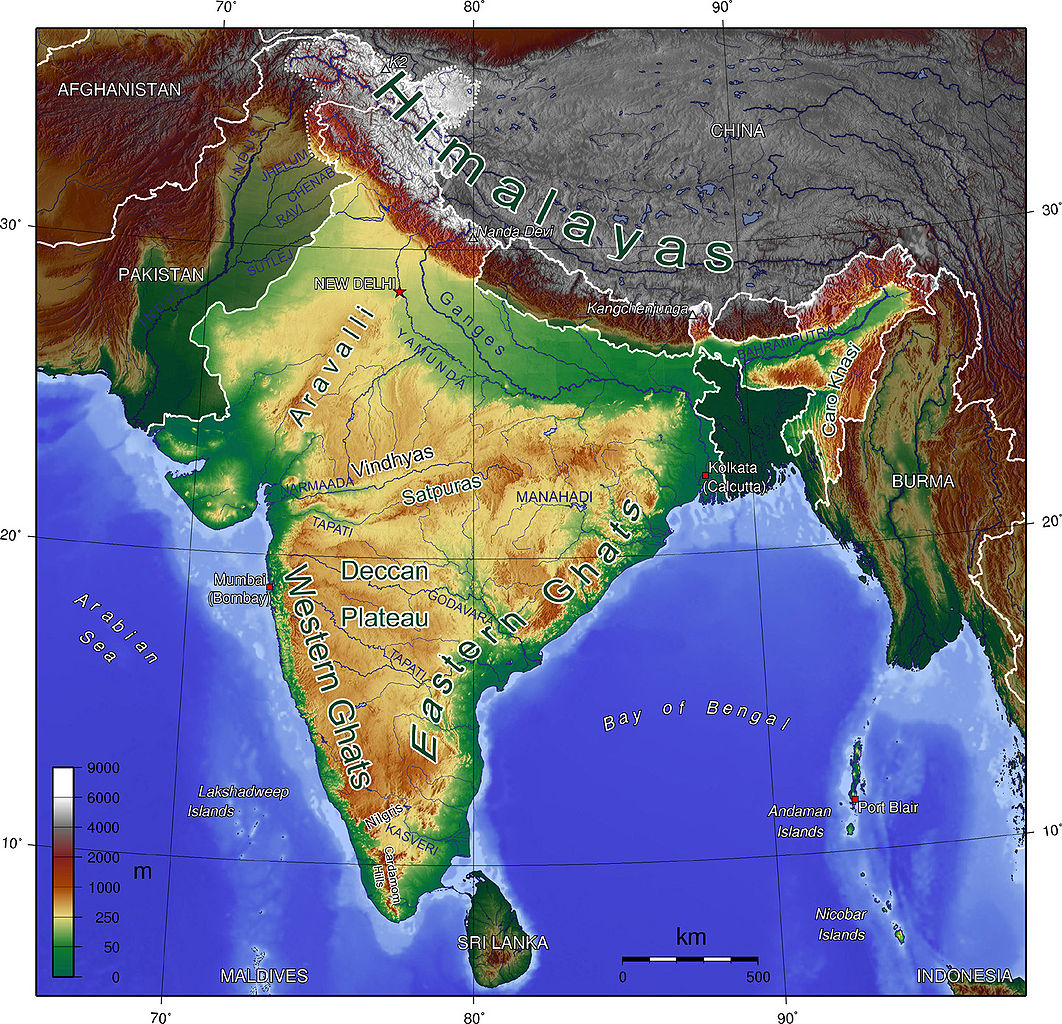

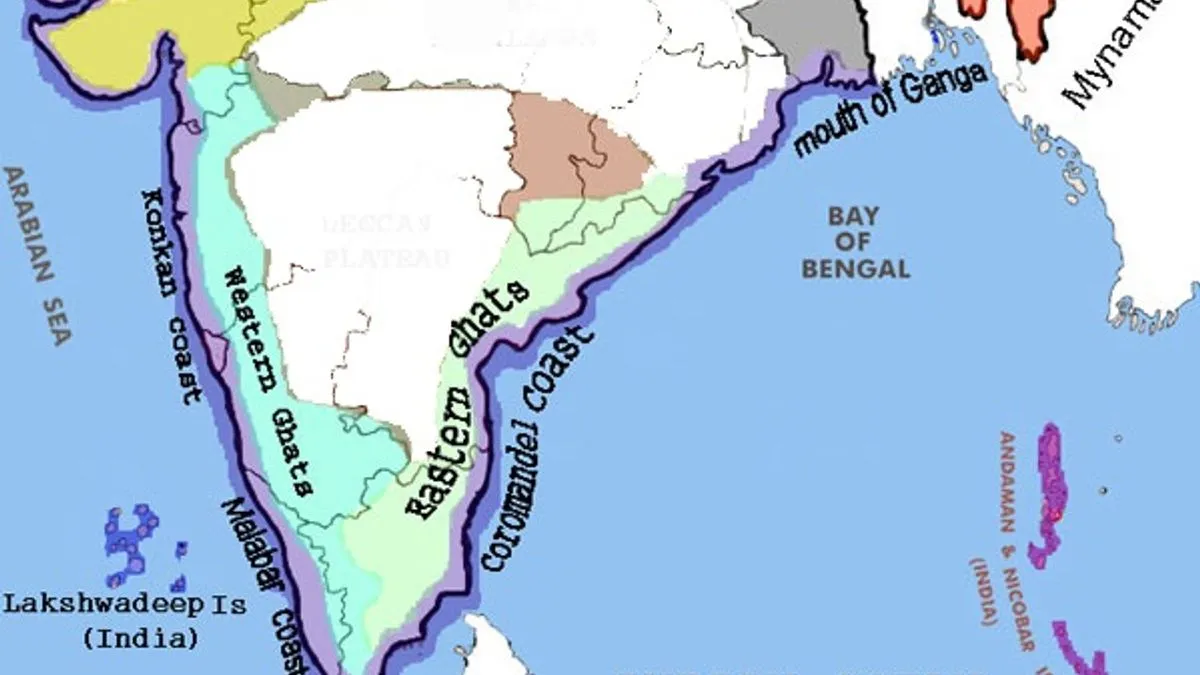

Sri Madhvacharya, also known simply as Madhva, was born in 1238 in Pajaka, a small village near Udupi in the present-day state of Karnataka. He is renowned as the founder of the Dvaita or dualism school of Vedanta philosophy, which he called Tattvavada, meaning “arguments from a realist viewpoint”.

Madhvacharya’s life was marked by extraordinary events from the very beginning. According to hagiographies, his birth was accompanied by divine signs and miracles. His parents, Madhyageha Bhatta and Vedavati had long yearned for a child and considered his birth a blessing from Lord Vishnu. Even as a young boy, Madhvacharya displayed remarkable intelligence and spiritual inclination. At the tender age of five, he received spiritual initiation, and by twelve, he had already accepted sannyasa, the most renounced order of spiritual life. This early renunciation set the stage for his lifelong dedication to spiritual pursuits and philosophical inquiry.

Madhvacharya’s contributions to Indian philosophy and theology are vast and enduring. His accomplishments can be broadly categorized into philosophical, literary, and social reforms.

Madhvacharya’s most significant contribution was the formulation and propagation of the Dvaita or dualism school of Vedanta. This philosophy stands in contrast to the Advaita or non-dualism philosophy of Adi Shankara and the Vishishtadvaita or qualified non-dualism of Ramanuja. The Dvaita philosophy asserts that there are fundamental differences between the individual soul or jiva, matter or prakriti, and God or Ishvara.

Madhvacharya propounded the concept of five-fold differences or pancha bheda. The pancha bheda is was the difference between God and the individual soul; the difference between God and matter; the difference between individual souls; the difference between soul and matter; and the difference between various forms of matter.

Madhvacharya identified Vishnu as the Supreme Being, equating Him with Brahman as described in the Upanishads. Unlike some other Indian philosophical schools that viewed the world as an illusion, Madhvacharya asserted that the world is real and not merely an illusion or maya. Controversially, Madhvacharya proposed that some souls are eternally destined for hell, a concept not commonly found in Hindu philosophy.

Madhvacharya was a prolific writer, authoring numerous works that expounded his philosophy and interpreted sacred texts. His literary output is impressive, with thirty-seven works attributed to him. Some of his most important works include commentaries on the thirteen principal Upanishads, offering his unique interpretations of these ancient texts. His commentary on the Brahma Sutras, the foundational text of Vedanta philosophy, is considered one of his most important works. Madhvacharya’s commentary on the Bhagavad Gita provides insights into his understanding of karma yoga and bhakti yoga and the Mahabharata Tatparya Nirnaya presents his interpretation of the Mahabharata, emphasising its spiritual and philosophical aspects. The Bhagavata Tatparya Nirnaya is a commentary on the Bhagavata Purana, this work elucidates Madhvacharya’s views on devotion to Vishnu while the Anu-Vyakhyana, considered his masterpiece, is a supplement to his commentary on the Brahma Sutras.

Madhvacharya was not just a philosopher but also a social reformer. He challenged prevailing social norms and worked towards making spiritual knowledge accessible to all. Madhvacharya declared that the path to salvation was open to all, regardless of caste or birth. This was a revolutionary idea in medieval India, where spiritual knowledge was often restricted to upper castes. He established the Ashta Mathas or Eight Monasteries in Udupi, which became centres of learning and spiritual practice. Madhvacharya emphasized bhakti or devotion as a means of spiritual realisation, making spirituality more accessible to the common people.

The life of Madhvacharya is replete with stories of miraculous events and divine interventions. While these stories may be viewed as hagiographical embellishments, they form an integral part of the tradition and reflect the reverence in which Madhvacharya is held by his followers.

According to tradition, Madhvacharya’s birth was not ordinary. It is said that his parents had been childless for many years and prayed fervently to Lord Ananteshwara, a form of Lord Vishnu for a son. Their prayers were answered, and Madhvacharya was born as an incarnation of Vayu, the wind god.

Several miraculous events are associated with Madhvacharya’s childhood. It is said that Madhvacharya’s father had accumulated many debts. To help repay these, young Madhva miraculously converted tamarind seeds into gold coins. Near Madhvacharya’s house lived a demon named Maniman in the form of a snake. The young Madhva is said to have killed this demon with the big toe of his left foot. Stories tell of Madhvacharya’s ability to appear instantly before his mother whenever she felt anxious, jumping from wherever he was playing. As a child, Madhvacharya is said to have consumed 4,000 bananas and thirty large pots of milk in one sitting, demonstrating his divine nature.

Madhvacharya is believed by his followers to be the third incarnation of Vayu, the wind god. According to this belief, the first incarnation was Lord Hanuman, the devoted servant of Lord Rama, the second was Bhima, one of the Pandava brothers in the Mahabharata while Madhvacharya was the third and final incarnation. This belief in Madhvacharya’s divine origin adds to his authority as a spiritual leader and philosopher in the eyes of his followers.

One of the most significant mythological stories associated with Madhvacharya is his supposed encounter with Vyasa, the legendary author of the Vedas and Puranas. According to tradition, Madhvacharya travelled to Badrikashrama in the Himalayas, where he met Vyasa in person. This meeting is said to have lasted for several days, during which Vyasa imparted advanced spiritual knowledge to Madhvacharya and confirmed the correctness of his philosophy.

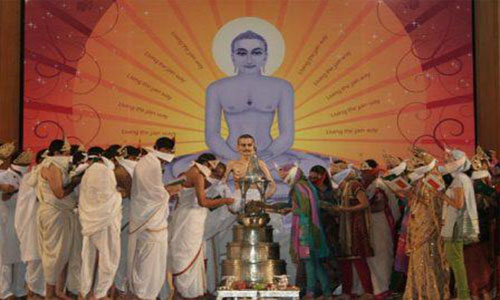

Madhvacharya Jayanti is celebrated with great devotion and enthusiasm, particularly in South India where his influence is strongest. The festival typically falls on the Vijaya Dashami day in the month of Ashwin, typically between September and October according to the Gregorian calendar.

Madhvacharya Jayanti serves multiple purposes. It’s a day to remember and honour the life and teachings of Madhvacharya. For followers of the Dvaita philosophy, it’s a time for spiritual introspection and renewal of their commitment to Madhvacharya’s teachings. The festival provides an occasion to educate people, especially the younger generation, about Madhvacharya’s philosophy and contributions to Indian thought. It brings together the community of Madhvacharya’s followers, strengthening their bonds and shared spiritual heritage.

The celebration of Madhvacharya Jayanti involves various rituals and activities. Temples dedicated to Madhvacharya or those belonging to the Dvaita tradition conduct special pujas or worship ceremonies on this day. Devotees often engage in the recitation of Madhvacharya’s works or texts that he commented upon, such as the Bhagavad Gita. Scholars and spiritual leaders give discourses on Madhvacharya’s philosophy and its relevance in contemporary times. Many communities organise cultural programs featuring devotional music and dance performances. Following Madhvacharya’s teachings on social reform, many followers engage in charitable activities on this day. Some devotees observe a fast on this day as a form of spiritual discipline and many try to visit Udupi, the centre of Madhvacharya’s activities, or other places associated with his life.

Madhvacharya’s influence extends far beyond his immediate followers. His ideas have had a lasting impact on Indian philosophy and spirituality. Madhvacharya’s philosophy significantly influenced later Vaishnava thinkers. The founder of Gaudiya Vaishnavism, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, and his followers thoroughly studied Madhvacharya’s works before developing their philosophy. The prominent Gaudiya Vaishnava theologian, Jiva Goswami, drew heavily from Madhvacharya’s writings in composing his works.

Madhvacharya’s emphasis on devotion or bhakti as a means of spiritual realisation contributed to the broader Bhakti movement in India. His teachings helped make devotional practices more accessible to common people, regardless of their caste or social status. Madhvacharya established a strong tradition of disciplic succession. Notable scholars in this lineage include Jayatirtha, Vyasatirtha, and Raghavendra Tirtha, who further developed and propagated Dvaita philosophy.

The eight mathas or monasteries established by Madhvacharya in Udupi continue to be important centres of learning and spiritual practice. The most famous among these is the Udupi Krishna Matha, known for its unique tradition of Krishna worship.

Madhvacharya identified Vishnu as the Supreme Being, possessing infinite auspicious qualities. He taught that God is independent and self-existent; the world is dependent on God for its existence and functioning; God is the efficient and material cause of the universe; and divine grace is essential for salvation.

Regarding the individual soul or jiva, Madhvacharya taught that souls are eternal and innumerable, each soul is unique and maintains its individuality even after liberation, the soul is inherently dependent on God, and knowledge of one’s true nature as a servant of God is crucial for spiritual progress.

Unlike some Indian philosophical schools that view the world as an illusion, Madhvacharya asserted that the world is real, not illusory, the diversity we see in the world is real and not merely an appearance, and the world is subject to God’s control and exists for His pleasure.

Madhvacharya outlined a clear path to spiritual liberation. These are Knowledge or Jnana which is understanding the nature of God, soul, and the world; devotion or Bhakti which means cultivating loving devotion to Lord Vishnu; detachment or Vairagya by which one develops dispassion towards worldly pleasures, and divine grace because ultimately, liberation depends on God’s grace.

A unique aspect of Madhvacharya’s philosophy is the concept of gradation among souls. He proposed that souls are categorised based on their inherent qualities and potential for liberation and some souls are destined for eternal liberation, some for eternal bondage, and others which will oscillate between the two states. This concept of gradation and eternal damnation for some souls has been one of the more controversial aspects of Madhvacharya’s philosophy.

While Madhvacharya lived and taught in the 13th century, his ideas continue to be relevant in the modern world. His emphasis on the reality of difference resonates with modern ideas of pluralism and diversity. The concept of each soul being unique underscores the importance of individual worth and potential. Madhvacharya’s emphasis on righteous living and devotion provides a framework for ethical behavior in daily life. His approach to critically examining existing philosophies encourages intellectual inquiry and debate. The view of the world as real and valuable can foster a sense of responsibility towards the environment.

Like any philosophical system, Madhvacharya’s Dvaita has faced challenges and criticisms. The idea that some souls are eternally condemned has been difficult for many to accept. Critics argue that Madhvacharya’s conception of God is too anthropomorphic. Some scholars have questioned Madhvacharya’s interpretations of Vedic texts, arguing that they are sometimes forced to fit his philosophical framework. Critics have pointed out perceived logical inconsistencies in some aspects of Dvaita philosophy. Despite these challenges, Madhvacharya’s philosophy continues to thrive and evolve, with modern scholars offering new interpretations and defences of his ideas.

While Madhvacharya Jayanti is primarily celebrated in India, particularly in the southern states, it has gained recognition globally due to the spread of Hinduism and the growing interest in Indian philosophy. The epicentre of Madhvacharya Jayanti celebrations is Udupi, Karnataka, where Madhvacharya established his primary matha. The Krishna Temple here becomes a focal point of festivities. Throughout Karnataka, especially in coastal regions, temples and mathas organise special pujas, discourses, and cultural programs. Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, and Kerala also see significant celebrations, particularly in areas with a strong Madhva following. While celebrations are less prominent in North India, some Vaishnava communities do observe the day with devotional activities.

Madhvacharya Jayanti is more than just a birthday celebration; it’s a testament to the enduring impact of a philosopher who lived over 700 years ago. Madhvacharya’s life, teachings, and legacy continue to inspire millions, offering a unique perspective on the nature of reality, the divine, and the human condition. His emphasis on the reality of difference, the supremacy of Vishnu, and the path of devotion has left an indelible mark on Hindu philosophy and practice. The annual celebration of Madhvacharya Jayanti serves as a reminder of his contributions and an opportunity for spiritual renewal for his followers.

We’re reminded of the rich philosophical traditions of India and their continued relevance in our modern world. Whether one agrees with all aspects of his philosophy or not, there’s no denying the profound impact Madhvacharya has had on Indian thought and spirituality.