The ceiling fan creaked its familiar rhythm above the dining table as Ramesh spread the morning’s Deccan Herald across the wooden surface. The monsoon had finally retreated from Bangalore, leaving behind the kind of crisp October morning that made the city feel like a hill station. Through the open windows of their Jayanagar home, the sounds of the awakening neighbourhood drifted in: the milk vendor’s bicycle bell, the vegetable seller’s melodic calls, and somewhere in the distance, the gentle hum of a BMTC bus navigating the tree-lined streets.

“Appa, look at this,” Ramesh called to his father, Krishnamurthy, who was performing his morning surya namaskars in the small front yard. He pointed to a full-page advertisement that had caught his eye. A gleaming red car dominated the page, with bold letters proclaiming: “MARUTI 800 – A CAR FOR THE MIDDLE CLASS.”

Krishnamurthy finished his final salutation to the sun and walked over, adjusting his steel-rimmed glasses. At seventy-two, he moved with the measured dignity of a retired government clerk who had spent four decades navigating the bureaucratic corridors of Vidhana Soudha. “Twenty-eight thousand rupees,” he read aloud, his voice carrying the weight of consideration. “That’s more than your annual salary, kanna.”

“But Thatha, think about it,” piped up Kavitha, the younger of Ramesh’s two daughters. At twelve, she possessed an infectious enthusiasm that could convince anyone of anything. “No more waiting for buses in the rain. No more walking to the market when Amma’s back hurts.”

Her older sister Priya, sixteen and perpetually practical, looked up from her mathematics textbook. “And how exactly do we afford it? We can barely manage Kavitha’s school fees.”

Sunita emerged from the kitchen, wiping her hands on her cotton saree. After seventeen years of marriage to Ramesh, she had learned to read the dreamy expression that crossed his face whenever he encountered something that represented progress, modernity, or simply the possibility of a better life for his family. This morning, that expression was unmistakable.

“You’re actually considering this, aren’t you?” she asked, settling beside him at the table.

Ramesh worked as an engineer at Bharat Electronics Limited, one of the few government jobs that paid well enough to support a joint family in middle-class comfort. Their house in 4th Block, Jayanagar, two bedrooms, a hall, a kitchen, and the luxury of a separate bathroom, represented years of careful saving and his father’s prudent investment in real estate when the area was still considered the outskirts of Bangalore.

“The waiting list is already six months long,” Ramesh said, continuing to study the advertisement. “If we don’t book now, it’ll be two years before we see one.”

Krishnamurthy settled into his chair with a thoughtful grunt. He had witnessed India’s transformation from British rule through independence, and now, at the tail end of the 1980s, he was watching his country embrace modernity with unprecedented enthusiasm. The Maruti factory in Gurgaon, the result of Indira Gandhi’s collaboration with Suzuki, represented something he had never imagined in his youth: mass-produced cars that ordinary families might actually afford.

“In my day,” he began, and Kavitha rolled her eyes affectionately, “a man was proud to own a bicycle. Your uncle Venkatesh saved for three years to buy his Hercules.”

“But times are changing, Appa,” Sunita said gently. “The children’s school is getting farther as the city grows. And my arthritis makes those bus rides increasingly difficult.”

Priya closed her textbook with a decisive snap. “If we’re going to dream, let’s dream properly. I’ve heard that the car comes in different colours. Red, white, blue…”

“Red,” Kavitha declared immediately. “It has to be red. Like the hibiscus flowers in Lalbagh.”

Over the next few weeks, the Maruti became the gravitational centre around which all family conversations orbited. Ramesh visited the showroom in Malleshwaram three times, each visit revealing new details that he would share over dinner. The car had a four-stroke engine, unlike the temperamental two-stroke scooters that dominated Bangalore’s roads. It could seat five people comfortably, well, four adults and one child. The fuel efficiency was extraordinary: twenty kilometres per litre.

Krishnamurthy accompanied his son on the fourth visit, partly out of curiosity and partly out of paternal duty to ensure that Ramesh wasn’t being swept away by sales rhetoric. The showroom itself was a revelation: gleaming white tiles, air conditioning, and salesmen in pressed shirts who spoke about “features” and “specifications” with the enthusiasm of cricket commentators.

“Sir, the Maruti 800 represents the future of Indian transportation,” the salesman explained to Krishnamurthy with respectful deference to his age. “Reliable, economical, and built with Japanese technology adapted for Indian conditions.”

Krishnamurthy ran his weathered hands over the smooth red surface of the display model. The paint was flawless, the chrome bumpers caught the showroom lights perfectly, and the interior smelled of new vinyl and possibility. Despite himself, he was impressed.

The family held a formal meeting that evening, seated in a circle on the cool terrazzo floor of their front room. This was how the Krishnamurthy household had always made important decisions, democratically, with even the youngest member having a voice.

“The mathematics are challenging but not impossible,” Ramesh began, consulting a notebook filled with calculations. “The down payment is eight thousand rupees. We have six thousand in savings, and I can borrow two thousand from the office cooperative society.”

“What about the monthly payments?” Priya asked. Her practical nature had blossomed into a genuine aptitude for numbers, much to her father’s pride.

“Four hundred and fifty rupees for four years. Plus insurance, registration, and maintenance.”

Sunita looked worried. “That’s nearly half your salary, Ramesh.”

“But think of what we’ll save,” Kavitha interjected. “No more auto-rickshaw fares. No more bus tickets. Amma, you could come to school for my annual day without worrying about the heat.”

Krishnamurthy had remained silent throughout this discussion, but now he cleared his throat. “There is another consideration,” he said slowly. “What will the neighbours think?”

This was not vanity speaking, but practical social wisdom. In the close-knit community of 4th Block Jayanagar, where everyone knew everyone else’s business, the arrival of a car would mark the family as either admirably prosperous or dangerously extravagant, depending on one’s perspective.

“Mrs. Lakshmi next door will probably faint,” Sunita said with a smile. “She still thinks our telephone is an unnecessary luxury.”

“But Mr. Rao across the street has been talking about buying a scooter,” Priya pointed out. “And the Sharmans in the corner house just bought a television.”

The decision, when it finally came, was typically understated. Krishnamurthy simply nodded and said, “If it will make life easier for my daughter-in-law and granddaughters, then we should proceed.”

The booking was made on a Tuesday morning in November. Ramesh took leave from work, dressed in his best white shirt and pressed trousers, and accompanied his father to the showroom. The formalities were surprisingly complex: forms to be filled, documents to be verified, and a waiting list number to be assigned: 2,847.

“Six to eight months for delivery,” the salesman explained. “Demand is very high, sir. The entire country wants a Maruti.”

The wait began.

Winter settled over Bangalore with its characteristic gentleness, cool mornings that warmed into pleasant afternoons, clear skies that revealed the distant Nandi Hills, and evenings perfect for long walks around the neighbourhood. The family’s anticipation grew in parallel with the passing months.

Kavitha developed the habit of walking past other Maruti cars whenever she spotted them on the street, studying their features and comparing them to her memory of the showroom model. She became an expert on the subtle differences between the various colours, the advantages of the deluxe model over the standard, and the proper pronunciation of “Suzuki.”

Priya, meanwhile, had begun learning to drive on her uncle Venkatesh’s scooter, arguing that someone in the family should be prepared to handle their new automobile. Her grandfather watched these lessons with a mixture of pride and terror, remembering when women in his family had rarely left the house unaccompanied, let alone operated motorised vehicles.

Sunita found herself calculating and recalculating the family budget, shifting small amounts between savings and expenses to ensure they could meet the monthly payments without compromising on education or healthcare. She also began scouting locations for a parking space, since their narrow house had no garage.

Ramesh threw himself into research with the dedication of an engineer. He borrowed books about automobile maintenance from the BEL library, studied traffic rules with the intensity of a law student, and began a notebook documenting every Maruti owner he met and their experiences with the car.

Spring arrived early in 1989, bringing with it the jasmine season and a telephone call that sent Kavitha racing through the house like a messenger from the gods.

“It’s ready! It’s ready! The showroom called, our car is ready!”

The delivery was scheduled for a Saturday morning, allowing the entire family to participate in this momentous occasion. They dressed as if for a wedding: Krishnamurthy in his silk dhoti and cream kurta, Sunita in her best Mysore silk saree, the girls in matching pavadai-davani sets that their grandmother had stitched specially for the occasion.

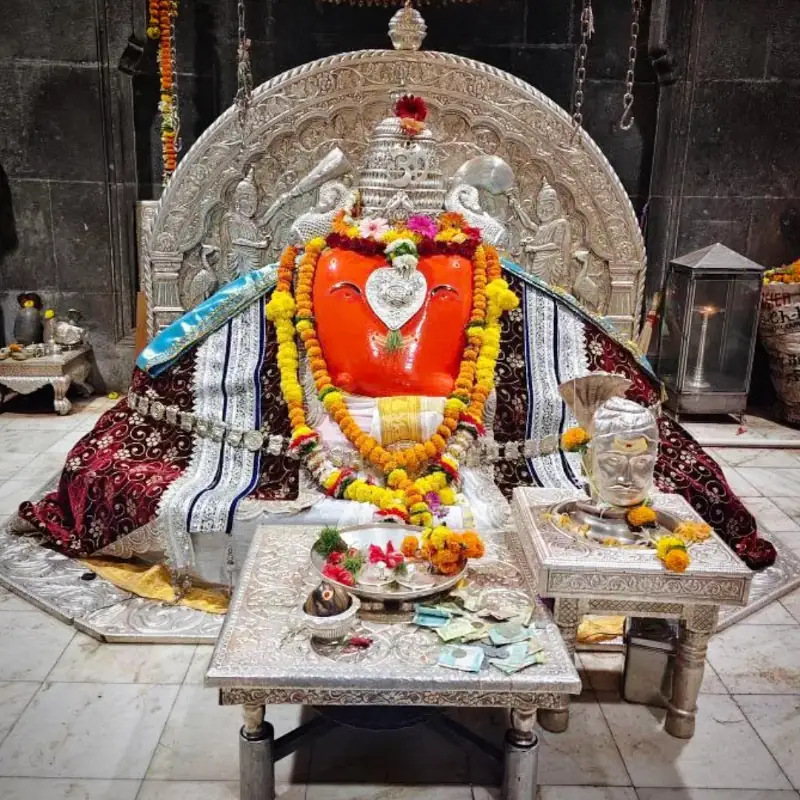

The showroom had transformed their transaction into a celebration. The red Maruti 800 sat in the centre of the display area, draped with marigold garlands and adorned with a small silver Ganesha idol on the dashboard. A photographer captured the moment as Ramesh accepted the keys from the showroom manager, his family gathered around him with expressions of joy and pride.

“Congratulations, sir,” the manager said formally. “May this car bring your family many years of happiness and safe travels.”

The drive home was a journey of barely three kilometres that felt like an odyssey. Ramesh gripped the steering wheel with both hands, maintaining a steady speed of twenty kilometres per hour while his passengers provided a constant stream of commentary.

“The engine is so quiet!” Sunita marvelled.

“Look how smoothly it turns!” Priya observed.

“Everyone is staring at us!” Kavitha announced with unabashed delight.

And indeed, their progress through Jayanagar resembled a slow-motion parade. Neighbours emerged from their houses to wave and smile. Children on bicycles rode alongside them for short distances. Even the traffic constable at the 4th Block intersection offered a salute as they passed.

Back home, a crowd had gathered. Mrs. Lakshmi from next door stood with her hands folded in namaste, genuinely happy for her neighbours despite her initial scepticism about their extravagant purchase. The Sharmans brought sweets. Mr. Rao from across the street walked around the car twice, examining it with the thoroughness of a prospective buyer.

“Beautiful colour,” he declared finally. “Very auspicious.”

Krishnamurthy performed a small puja, breaking a coconut near the front wheel and sprinkling the car with holy water from their morning prayers. It was a synthesis of ancient ritual and modern technology that perfectly captured the spirit of changing India.

The first family outing came the following day, a Sunday drive to Lalbagh Botanical Gardens. What had previously been a complex expedition involving bus connections and considerable walking was now a simple matter of driving to the parking area and walking directly to the glasshouse.

They spent the afternoon among the flower displays, but the real entertainment was watching other families admire their car in the parking lot. The red Maruti had developed a small court of admirers, children who pressed their noses against the windows, adults who walked around it appreciatively, and fellow car owners who struck up conversations with Ramesh about mileage and maintenance.

“It’s like owning a celebrity,” Sunita whispered to her husband as yet another stranger approached to ask about their driving experience.

The car transformed their daily routines in ways both large and small. Grocery shopping became a family affair, with weekend trips to Russell Market that would have been impossible with public transportation. Sunita’s visits to the temple expanded from the neighbourhood Ganesha temple to the grand Dodda Ganesha Temple in Basavanagudi. The girls’ social world expanded as drop-offs and pick-ups from friends’ houses became feasible.

Most importantly, the car seemed to expand their sense of possibility. When Kavitha’s school announced a field trip to Mysore, the family was able to offer to drive some of her classmates, turning the journey into an adventure rather than an expensive impossibility. When Priya received admission to the prestigious National College for her pre-university studies, the daily commute became manageable rather than prohibitive.

Six months after the delivery, Ramesh calculated that they had driven nearly eight thousand kilometres, trips to relatives in Mysore, weekend outings to Nandi Hills, and countless small journeys that had previously required careful planning and considerable expense.

“The car has paid for itself in saved bus fares and auto-rickshaw rides,” he announced at dinner one evening.

“No,” Krishnamurthy corrected gently. “The car has paid for itself in possibilities we never imagined.”

As 1989 drew to a close, the red Maruti had become as much a part of the family as any human member. It had its own personality, a slight reluctance to start on particularly cold mornings, a preference for being parked in the shade, and a tendency to attract admiring glances wherever it went.

On New Year’s Eve, as fireworks lit up the Bangalore sky and the family stood in their front yard reflecting on the year that had passed, Kavitha made an observation that would be repeated in family stories for years to come.

“You know,” she said, leaning against the warm red hood of their car, “I think this is the year we stopped just dreaming about the future and started driving toward it.”

The adults smiled at her earnestness, but privately, each of them acknowledged the truth in her words. The little red Maruti had done more than provide transportation—it had carried them into a new version of themselves, a family unafraid to embrace change and confident enough to believe that better days lay ahead.

In the distance, a church bell tolled midnight, welcoming not just a new year but a new decade. The 1990s stretched ahead, full of promise and possibility, and the Krishnamurthy family was ready for the journey.