Overconsumption means using more than what we really need. It’s a problem that touches everything, from the environment to our mental well-being. But before blaming just the consumers, it’s worth asking: What exactly drives this urge to keep buying and consuming? And is it really all bad, or are some concerns overplayed?

At first glance, overconsumption seems like a simple case of excess: people buying too much stuff or eating more than necessary. But this view misses a deeper truth. It’s not just about individuals wanting more. It’s about the system built to encourage constant growth and sales. Technology, advertising, social pressure, and economies built on endless expansion all play a massive role.

Take technology. It’s easier than ever to buy things online, sometimes the same day. Advertisers now target people with precision, bombarding them with reasons to buy more. This isn’t just marketing tactics; it changes how people think and feel. The convenience of online shopping removes natural limits that might normally curb spending. So, while people are responsible for their choices, the environment they live in nudges them towards overconsumption.

Another driver is social media and the desire to ‘keep up.’ We see others’ lifestyles, possessions, and travels. That creates an invisible pressure to match or surpass. But does this really lead to happiness? Studies show it doesn’t. Instead, it can cause stress, anxiety, and feelings of inadequacy. Buying stuff provides a short thrill but doesn’t solve deeper personal or social issues.

On the flipside, some argue that consumption is normal and needed for economic growth and prosperity. Economies thrive on sales and production. If people stop buying, jobs and livelihoods suffer. This argument often clashes with environmental calls to reduce consumption. So, there’s a tension: How do we balance economic needs with ecological limits?

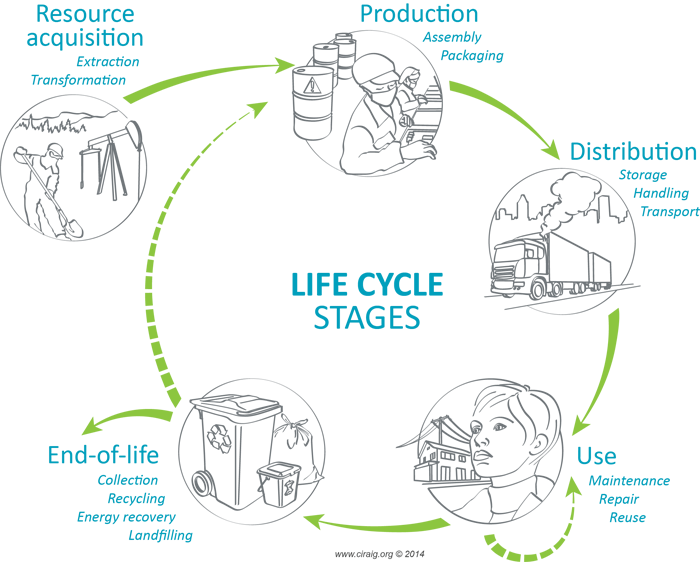

The environmental impact of overconsumption is undeniable. More production means more resource depletion, energy use, pollution, and waste. The planet’s ecosystems suffer, forests shrink, oceans fill with plastic, and the air we breathe worsens. Climate change accelerates as a result. These consequences are not abstract; they threaten the quality of life for future generations.

But not everyone contributes equally. Wealthier countries and individuals consume far more resources than poorer ones. Average citizens in rich countries use many times the resources that those in low-income nations do. That raises ethical questions: why do some live in excess while others lack essentials? Overconsumption, therefore, is more than a personal habit; it is deeply tied to inequality and global justice.

Food waste highlights overconsumption’s complexity. A massive amount of edible food ends up in landfills because people buy more than they can eat or misunderstand expiration labels. This waste adds another layer of environmental harm: methane emissions from rotting food, wasted water, and energy used to produce it all. Fixing this problem requires better education, smarter shopping habits, and less production driven by excess demand.

There is also an important psychological side. Overconsumption often serves as a way to cope with boredom, stress, or low self-esteem. Buying things or eating more can offer temporary relief from uncomfortable feelings. But this creates a vicious circle; short-term happiness leads to long-term dissatisfaction and more consumption to fill the void again. This pattern is unsustainable for both people and the planet.

Consumer culture encourages this cycle by linking identity and status to what we own. Possessions are seen as marks of success or social belonging. But this material focus can weaken community bonds and increase loneliness, as social life shifts from shared experiences to individual consumption. Over time, this damages social well-being.

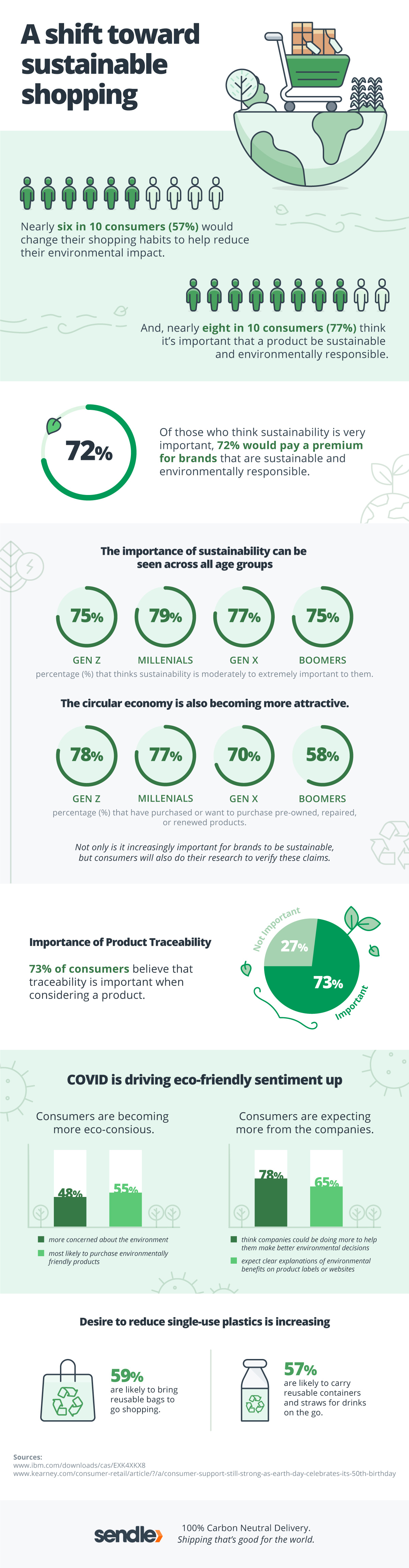

Some solutions have emerged, but are complicated. Sustainable products and ethical brands offer alternatives, but often come with higher prices that not everyone can afford. This creates a privilege gap where only some can choose to consume responsibly. Legislative action, like taxes on pollution or incentives for sustainable production, is necessary but politically difficult to implement.

A more radical idea is shifting from a growth-based economy to one focused on well-being and ecological balance. This would require redefining progress not by how much we produce or consume but by how good life is for people and nature. It demands changing lifestyles, values, and expectations at scale, which sounds daunting but might be the only way forward.

Individuals can reduce their contribution to overconsumption by adopting practical, mindful habits that focus on consuming less, buying better, and wasting less. The key is to be intentional with consumption choices and challenge the impulse to buy unnecessarily.

Some straightforward steps include:

- Be mindful before buying. Ask if an item is truly needed or just a temporary want. Avoid impulse purchases, especially when emotional or distracted. This mindset can break the cycle of buying to fill emptiness.

- Shop locally and support sustainable brands. Buying from local shops reduces the environmental costs of transport and packaging while supporting community economies. When purchasing new items, favour companies using sustainable and ethical production methods, often resulting in better-quality products.

- Buy less, buy better. Focus on durable, long-lasting products rather than cheap, disposable ones. This reduces waste and lessens the demand for constant production.

- Use second-hand or borrow. Buying second-hand clothes, furniture, or electronics can significantly reduce resource use. Borrow items you only need occasionally rather than buying them.

- Plan meals and reduce food waste. Make shopping lists that align with planned meals. Compost food scraps and avoid overbuying to cut food waste, a major contributor to overconsumption’s environmental impact.

- Repair and upcycle. Instead of throwing away broken or old items, repair them or find new uses to extend their life.

- Cancel unused subscriptions and avoid habitual consumption. Gym memberships, magazine subscriptions, or services not actively used add unnecessary consumption and spending.

- Reduce energy and water use. Small actions like using energy-efficient appliances, turning off unused electronics, or washing dishes efficiently can reduce resource consumption.

- Adopt minimalist principles. Declutter belongings to prioritise what is meaningful and avoid hoarding stuff out of habit or social pressure.

- Shift transportation habits. Walk, bike, use public transit, or carpool to reduce fossil fuel consumption related to travel.

These steps may seem small individually, but they can collectively reduce demand. They require conscious effort to change habits and resist constant consumer culture pressures. The goal is not perfection but progress towards more sustainable living.

Ultimately, individuals can reduce overconsumption by staying mindful, making informed choices, and valuing quality over quantity. This frees people from endless cycles of want and waste, benefiting both personal well-being and the planet.

Still, it is important to question some assumptions. Is all consumption bad? Some say no. Consumption drives innovation, provides comfort, and supports livelihoods. The issue is excess, overuse beyond what is sustainable or necessary. Finding that threshold is tricky. It varies by context, culture, and individual needs.

Ultimately, overconsumption is not just a personal failing or a simple market outcome. It’s a complex problem rooted in economic systems, social norms, psychological needs, and technological changes. Addressing it takes honesty about what drives us, courage to challenge dominant narratives, and collective action to create fairer and more sustainable futures.