Bheemeswara Swami Temple, Draksharamam, Andhra Pradesh

Nestled in the lush landscapes of Andhra Pradesh, the Manikya Amba Shaktipeeth, also known as the Bheemeswara Swami Temple is located in Draksharamam, Kakinada district. As one approaches the temple, the imposing structure comes into view, its towering gopuram reaching skyward, adorned with intricate sculptures that tell tales of divine exploits and cosmic battles. One of the Pancharama Kshetras, the temple complex, spread over 12 acres, is surrounded by high walls that seem to whisper secrets of bygone eras.

The origins of the Bheemeswara Swami Temple stretch back over a millennium. While the exact date of its establishment remains a subject of scholarly debate, inscriptions and architectural evidence suggest a rich history dating back to at least the 9th century. The temple’s construction is attributed to various dynasties that ruled the region, including the Eastern Chalukyas and the Cholas. Each ruling dynasty left its mark on the temple, contributing to its architectural grandeur and spiritual significance. The big Mandapam of the temple was built by Ganga Mahadevi, daughter-in-law of Eastern Ganga Dynasty king Narasingha Deva I of Odisha.

According to tradition, it is believed that the navel of Goddess Sati fell at this spot, making the Manikya Amba a Shaktipeeth. At Draksharamam, the Bhairava is known as Bhimeswara, lending his name to the temple itself. The presence of both Shakti, in the form of Manikya Amba, and Shiva, as Bhimeswara, creates a powerful spiritual synergy, symbolising the union of divine masculine and feminine energies.

The Bheemeswara Swamy Temple spans over 12 acres and features high walls that enclose several shrines dedicated to various deities within its premises. The sanctum sanctorum or the garbha griha houses an intricately decorated Shiva Linga surrounded by exquisite carvings representing cultural grandeur from bygone eras. The inscriptions on its walls are written in multiple languages such as Telugu, Kannada, Tamil, and Sanskrit—reflecting contributions from different dynasties over centuries.

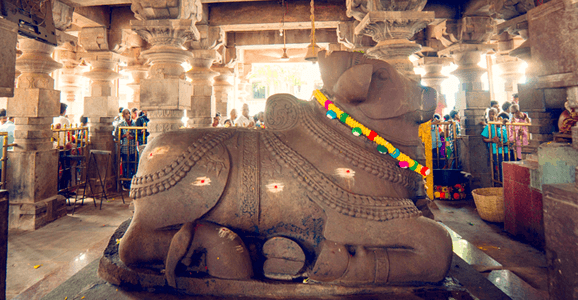

As one wanders through the temple complex, several unique features capture the attention. The sanctum houses a tall octagonal lingam, accessible through a pradakshina patha or circumambulatory path. This lingam is the focal point of worship and is believed to possess immense spiritual power. A special Nandi idol, known as Ekasila Nandi, is carved from a single stone, showcasing the exceptional craftsmanship of ancient artisans. At the entrance, a magnificent dancing Ganapati welcomes visitors. Uniquely, the trunk of Lord Ganesh is turned to the right, a rare and auspicious feature. During the months of Chaitra and Vaisakha, usually between March and May, a celestial spectacle occurs. The early morning sunlight touches the feet of the deity, while in the evening, it illuminates the feet of the goddess, creating a mesmerising play of light and shadow. Within the temple complex, one can find a small stone model of the temple.

Unlike most temples where male deities dominate worship practices, Draksharamam gives equal importance to Manikyamba Devi or Goddess Parvati. This unique aspect makes it one of the few pilgrimage centres where both male and female deities are equally revered. Manikyamba Devi faces south in her shrine within the temple complex—a rare positioning symbolising her role as a guardian deity protecting devotees from negative energies.

The temple follows a strict schedule, opening its doors to devotees from 6 am to 8 pm, with a brief afternoon closure from 12 noon to 3 pm. Throughout the day, priests perform various pujas and rituals, invoking the blessings of Lord Bhimeswara and Goddess Manikya Amba. Devotees participate in these rituals, offering flowers, fruits, and prayers, seeking divine grace and protection.

The temple comes alive during its numerous festivals, each celebration adding vibrant hues to the spiritual canvas of Draksharamam. Observed on the 28th day of Magha in February/March, Maha Shivaratri is the main festival of the temple. Thousands of devotees flock to the shrine, observing fasts and participating in night-long vigils, reciting the Panchakshari mantra or reading Shiva Puranas. During this auspicious month of Karthika, in October/November, the temple is illuminated by thousands of lamps lit by devotees in honour of Lord Shiva and Goddess Manikyamba. The nine-night festival of Navaratri, known locally as Sarrannavarathri, celebrates the victory of Goddess Durga over evil. Held from Asviyuja Suddha Padyami to Dwadasi, usually in October, it’s a time of fasting, special prayers, and elaborate decorations. The Kartheeka Monday Festivals, along with the Jwalathoranam ritual, involve lighting thousands of lamps around the temple, symbolising the triumph of light over darkness. Sri Swamyvari Incarnation Day is celebrated on Margasira Suddha Chaturdhasi, usually in December, and honours the birth of Bhimeswara Swamy. Sri Swamyvari Kalyanam is the divine wedding celebration of Lord Bhimeswara and Goddess Manikyamba that takes place on Bhisma Ekadasi day in Magha Masam, usually in February. Elaborate rituals are performed to commemorate this celestial union.

Local lore suggests that the name Draksharamam is derived from Daksha Rama referring to the ashram of Daksha Prajapati, father of Goddess Sati. According to one tale, a devotee once offered grapes or draksha in Sanskrit to Lord Shiva at this temple. Miraculously, the grapes transformed into lingams, giving rise to the name Draksharamam. Draksharamam is one of the Pancharama Kshetras, a group of five ancient Shiva temples in Andhra Pradesh. Each of these temples is said to represent one of the five faces of Shiva, with Draksharamam representing the Tatpurusha face.

One of the most prominent legends associated with the Bheemeswara Swamy Temple is tied to the demon Tarakasura. According to the Shiva Purana and Skanda Purana, Tarakasura performed intense penance and was granted a boon by Lord Brahma that made him nearly invincible. He received the Atmalinga from Lord Shiva, which he placed in his throat as a source of immense power. Empowered by the Atmalinga, Tarakasura began terrorising the gods and sages. In response, the gods sought Lord Shiva’s help. Shiva created his son, Kumara Swamy or Lord Kartikeya, who was destined to defeat Tarakasura. During the battle, Kumara Swamy realized that the Atmalinga in Tarakasura’s throat was his source of invincibility. Using his divine weapon, Kumara Swamy shattered the Atmalinga into five fragments, which fell at different locations in Andhra Pradesh. These fragments became sacred Shiva Lingas worshipped at the Pancharama Kshetras. The piece of Atmalinga that fell at Draksharamam became known as Bheemeswara Swamy, named after its association with Lord Shiva and King Bhima of the Eastern Chalukyas.

Another fascinating story revolves around River Godavari’s connection to Draksharamam. It is believed that when a piece of Atmalinga fell here, sages requested River Godavari to sanctify it. However, Godavari delayed her arrival, prompting Lord Shiva to manifest himself directly at Draksharamam. Eventually, Godavari arrived with the blessings of the Saptarishis or the seven sages, dividing herself into seven streams known as Sapta Godavari Kundam near the temple. This sacred water body on the eastern side of the temple is considered highly auspicious for purification rituals and spiritual merit.

Legend has it that Sage Vyasa performed intense penance at Draksharamam to seek divine blessings. His devotion elevated Draksharamam’s sanctity further, earning it the title Dakshina Kasi or Southern Varanasi. This association with Vyasa underscores the temple’s importance as a centre for spiritual enlightenment.

The Bheemeswara Swami Temple exemplifies the Dravidian architectural style, characterised by its pyramidal tower, intricate stone carvings, and spacious courtyards. The temple walls serve as a historical record, etched with numerous inscriptions and epigraphs in various South Indian scripts. These provide valuable insights into the temple’s history and the socio-cultural context of different eras. The temple features two mandapas or halls supported by exquisitely carved pillars. These pillars are adorned with intricate patterns and figurines, each telling a story from Hindu mythology. The cloistered walkway, Tiruchuttumala, around the shrine includes 67 pillars, each adorned with intricate sculptures depicting dancers, musicians, and mythical figures. The sanctum sanctorum or the Garbhaalaya is a masterpiece of craftsmanship, its walls adorned with intricate decorations that reflect the cultural grandeur of bygone eras.

The Bheemeswara Swami Temple stands not just as a monument to faith, but as a bridge between the earthly and the divine, inviting all who visit to partake in its timeless spiritual journey. Whether one is drawn by its architectural splendour, its rich history, or its spiritual significance, the Manikya Amba Shaktipeeth in Draksharamam offers a profound experience that resonates long after one has left its hallowed grounds.

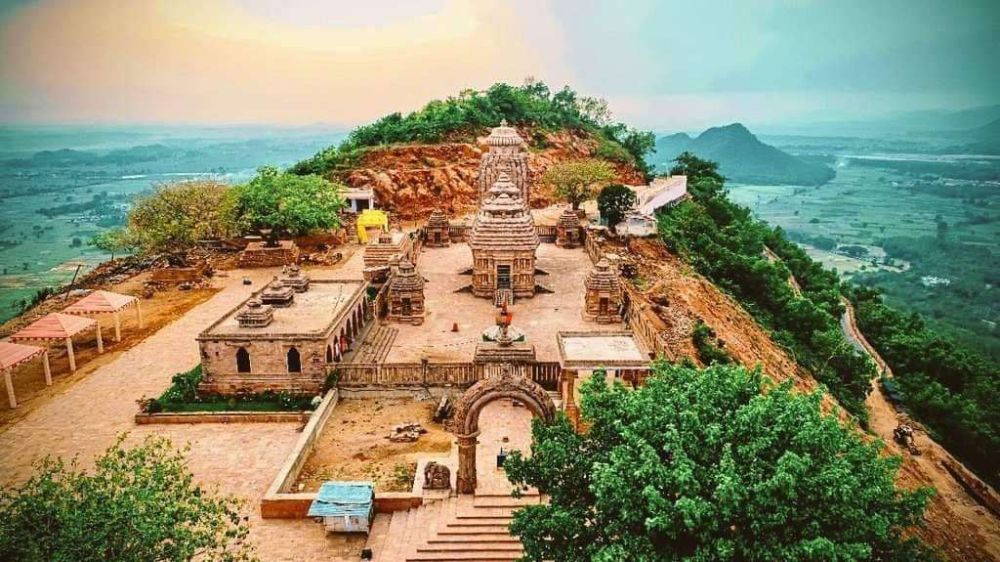

Srisailam Temple, Srisailam, Andhra Pradesh

Nestled atop the Nallamala Hills, the Srisailam Temple complex is home to two interconnected temples – the Mallikarjuna Temple dedicated to Lord Shiva, and the Bhramaramba Devi Temple honoring the divine feminine. Together, they form one of the most revered Shakti Peethas in India, drawing pilgrims from far and wide.

The origins of the Srisailam Temple complex date back centuries. Inscriptional evidence from the Satavahana dynasty suggests the temple’s existence as early as the 2nd century. However, the temple has evolved over centuries, with contributions from various dynasties. The Reddi Kingdom who ruled between the 12th and 13th centuries, made significant additions, including the construction of the veerasheromandapam and paathalaganga steps. The rulers of this dynasty were ardent devotees of Sri Bhramarambha Mallikarjuna Swamy. The most substantial renovations and expansions occurred during the reign of the Vijayanagara Empire in the 14th and 15th centuries. King Harihara I, in particular, is credited with major architectural enhancements that have shaped the temple’s current grandeur.

The Bhramaramba Devi Temple is one of the 18 Maha Shakti Peethas. According to tradition, it is believed that the neck of Goddess Sati fell here. At Srisailam, the Bhairava is Mallikarjuna himself, represented by the Mallikarjuna Temple adjacent to the Bhramaramba shrine. This unique arrangement, where both Shiva and Shakti have prominent temples side by side, creates a powerful spiritual synergy, symbolizing the union of divine masculine and feminine energies.

The presence of both Mallikarjuna and Bhramaramba temples in close proximity is a unique aspect of this Shakti Peetha. The idol of Bhramaramba Devi is depicted with eight arms, wearing a silk sari, embodying her multifaceted divine power. A Sri Yantra is installed in front of the main sanctum sanctorum, adding to the temple’s tantric significance. The temple showcases a harmonious blend of different architectural styles, reflecting its long history and patronage by various dynasties. The temple’s enclosure features Salamandapas on the northern and southern sides, adorned with intricate sculptural work. The Mukha Mandapa, a popular hall was constructed by the Vijayanagara Dynasty. The complex includes several other significant shrines, such as the Vriddha Mallikarjuna temple, Sahasra Lingeswara shrine, Uma Maheswara temple, and the Navabrahma temples.

The Srisailam Temple follows a strict schedule, opening its doors to devotees from 4:30 am to 10 pm. Throughout the day, priests perform various pujas and rituals, invoking the blessings of Lord Mallikarjuna and Goddess Bhramaramba. Devotees participate in these rituals, offering flowers, fruits, and prayers, seeking divine grace and protection. One unique aspect of worship here is the sanctification of Mahaprasad. The food offered to Lord Mallikarjuna is not considered Mahaprasad until it has been offered to Goddess Bhramaramba, highlighting the goddess’s supreme status at this site.

The temple complex comes alive during its numerous festivals. Maha Shivaratri is the most significant festival, celebrated with great fervour in February or March. Thousands of devotees observe fasts, participate in night-long vigils, and engage in the recitation of the Panchakshari mantra or reading of Shiva Puranas. The nine-day Brahmotsavam is a celebration, usually held in September or October, that sees the temple adorned with colorful decorations. Various rituals and processions create a joyous and festive atmosphere. The Telugu New Year, Ugadi, is marked by special prayers, cultural programs, and the offering of traditional dishes to the deities. During the month of Karthika, a month-long festival is dedicated to Lord Shiva and Goddess Parvati and involves fasting, special prayers, and religious activities throughout the auspicious month. Kumbhothsavam is considered the most significant festival of the Bhramaramba Devi Temple with various offerings to the goddess. It’s celebrated on the first Tuesday or Friday, whichever comes first, after the full moon day of Chaitram, the beginning month of the Indian calendar.

The name Bhramaramba means Mother of Bees. According to legend, the goddess assumed the form of a bee to worship Shiva at this site, choosing it as her abode. This connection to bees is central to the temple’s mythology. A popular legend tells of the demon Arunasura, who received a boon from Lord Brahma that he couldn’t be killed by any two or four-legged being. When he began terrorizing the world, the gods appealed to Goddess Durga. She took the form of Bhramari or Bhramarambika and created thousands of six-legged bees that ultimately defeated the demon. Another legend speaks of Shiva coming to Earth and marrying a Chenchu girl, who was Goddess Parvati in disguise. They settled in Srisailam, explaining the presence of both deities in the temple complex. Local Chenchu tribes refer to Lord Shiva as Chenchu Mallaya and worship both deities. The presence of both Mallikarjuna or Lord Shiva and Bhramaramba or Goddess Parvati temples side by side is said to represent their eternal union and their choice to reside together in Srisailam to bless their devotees.

One of the most beloved legends of the Srisailam Temple is the tale of Chenchu Mallayya, which ties Lord Shiva to the local Chenchu tribal community. According to this story, Lord Shiva once descended to the Srisailam forest in the form of a hunter. While wandering through the dense woods, he encountered a beautiful Chenchu girl and fell in love with her. The girl, who was none other than Goddess Parvati in disguise, reciprocated his feelings. The two were married and lived together on the hill. The Chenchu tribe reveres Lord Shiva as their relative and affectionately calls him Chenchu Mallayya with Mallayya meaning Lord Shiva. Even today, this story is depicted on the temple’s prakaram or outer walls, and the Chenchus are given special privileges at the temple. For instance, during Maha Shivaratri, members of the Chenchu tribe are allowed to perform abhishekam, the ritual bathing and puja for Lord Mallikarjuna Swamy, making this legend an enduring part of their identity.

The story of Princess Chandravati is another fascinating tale tied to the origins of the Srisailam Temple. Chandravati was a princess who fled her kingdom to escape her father’s wrath and sought refuge in the forests of Srisailam. While living there, she noticed a miraculous event: one of her Kapila cows stood under a Bilwa tree and shed milk over a natural rock formation resembling a Shiva Linga. Intrigued by this divine phenomenon, Chandravati began worshipping the Linga daily, offering garlands made from jasmine flowers, locally known as Malle. Her devotion pleased Lord Shiva, who appeared before her and blessed her. The Linga came to be known as Mallikarjuna with Mallika meaning jasmine and Arjuna referring to Shiva. Chandravati later built a grand temple around this self-manifested or Swayambhu Linga. It is said that Chandravati attained salvation or moksha through her unwavering devotion. Her story is immortalised in stone inscriptions within the temple complex, making her an integral part of its history.

The Srisailam Temple complex is not just a place of worship but is like stepping into pages of history, art, and spirituality with each stone, carving, and ritual carrying within it the devotion of countless generations, inviting one to become part of its continuing story.