The conference room on the thirty-eighth floor of the Raffles Place tower buzzed with polite conversation as executives filtered in for the quarterly review meeting. Marcus Lim straightened his tie and checked his watch. He was early, as always. The acquisition of NexaFlow had been his project from the start, and today’s meeting would finalise the partnership that could make his career.

He was scrolling through his tablet when she walked in.

The woman commanded attention without trying. Her navy blazer was perfectly tailored, accentuating curves that spoke of confidence rather than apology. Dark hair swept into an elegant chignon, framing a face that was striking in its intelligence; sharp cheekbones, full lips, and eyes that seemed to see everything. When she spoke to her assistant, her voice carried the kind of authority that came from earning respect, not demanding it.

Marcus found himself staring. She was easily the most captivating woman he’d ever seen.

“That’s Priya Kumar,” whispered his colleague, Wei Ming. “She built NexaFlow from nothing. Brilliant woman. A bit intimidating, though.”

Priya. The name suited her. Marcus watched as she took her seat at the head of the table, directly across from him. When their eyes met, he offered his most charming smile. She looked at him for a long moment, something flickering across her features, before nodding politely and turning away.

The meeting proceeded smoothly. Priya’s presentation was flawless, her responses to questions sharp and insightful. Marcus found himself genuinely impressed, not just attracted. This wasn’t just beauty and confidence; this was brilliance in action.

“Mr. Lim,” Priya’s voice cut through his thoughts. “I believe you had some concerns about our data security protocols?“

He recovered quickly, launching into his prepared questions. But throughout the discussion, he couldn’t shake the feeling that her dark eyes were studying him, measuring him against some invisible standard.

After the meeting, Marcus lingered, hoping to catch her alone.

“Ms. Kumar?” He approached with what he hoped was professional interest. “I was wondering if you’d like to grab dinner tonight. To discuss the partnership, of course.”

For just a moment, something raw and vulnerable flashed in her eyes. Then it was gone, replaced by polished professionalism.

“I don’t think that would be appropriate, Mr. Lim. All business matters can be handled during office hours.“

The rejection stung more than it should have. “Of course. Professional boundaries. I respect that.“

As he walked to his BMW in the Marina Bay Financial Centre car park, Marcus couldn’t understand why he felt like he’d failed some test he didn’t know he was taking.

Ten years earlier

Priya Raj pushed her thick glasses up her nose and clutched her textbooks tighter as she navigated the crowded NUS campus. At nineteen, she was already carrying more responsibility than most of her classmates could imagine: working two part-time jobs to help with family expenses while maintaining her first-class honours in computer science.

She’d learned to make herself invisible. It was easier that way.

“Alamak, is that the same blouse she wore yesterday?” The voice carried across the Arts Link, followed by barely suppressed laughter.

Priya’s cheeks burned, but she kept walking. The blouse was one of three she owned, all carefully maintained but obviously not from Orchard Road boutiques. She’d learned not to react to comments from Marcus Lim’s circle, the golden boys and girls who seemed to glide through university on charm and family connections.

Marcus himself had never been cruel, not directly. He simply… didn’t see her. When Professor Tan paired them for a programming project, Marcus had looked right through her as if she were furniture, immediately suggesting they meet at the coffee shop in the Science canteen where she worked, not knowing, of course, that she’d be serving him while trying to discuss their code.

“Can I get you anything else, ah?” she’d asked after bringing him his third kopi-O.

“Just working on this project with…” He’d glanced around vaguely. “Some girl from class lah. She’s supposed to be here.”

Priya had stood there in her coffee-stained uniform, textbook tucked under her arm, invisible.

Three weeks into the partnership negotiations, Marcus was no closer to understanding Priya Kumar. She was professional, brilliant, and completely unreachable. Every attempt at conversation beyond business was met with polite deflection. Every invitation was declined with perfect courtesy.

It was driving him crazy.

“You’re obsessing, bro,” Wei Ming observed over lunch at a trendy CBD restaurant. “It’s not like you. Usually, they’re all over you.”

Marcus poked at his laksa, watching the busy street through the floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking the Singapore River. “She’s different.”

“Maybe that’s the point. Maybe she sees right through your usual charm.”

That afternoon, Marcus found himself really looking at the people around his Shenton Way office. His secretary, who always seemed nervous. The junior associates who laughed too loudly at his jokes. The cleaning auntie who hurried past him as if afraid to be noticed.

When had he stopped seeing people as individuals?

The question haunted him through another sleepless night in his Sentosa Cove penthouse.

The breakthrough came during a crisis. A cybersecurity breach at one of Lim Holdings’ subsidiary companies threatened to derail not just the NexaFlow partnership, but several other major deals. Marcus worked through the night, coordinating responses from his corner office overlooking Marina Bay, when his phone rang.

“Mr. Lim? It’s Priya Kumar. I heard about the breach. I’m sending over my team.”

“You don’t have to—“

“My reputation is tied to this partnership now. We fix this together.”

For the next eighteen hours, they worked side by side. Marcus watched Priya command her team with quiet authority, solving problems with elegant efficiency. She ordered zi char for everyone, remembered the security uncle’s name, and somehow made the crisis feel manageable.

Around dawn, they found themselves alone in the conference room, surrounded by empty coffee cups and whiteboards covered in code, the Marina Bay Sands and Singapore Flyer silhouetted against the pink sunrise beyond the windows.

“Why?” Marcus asked quietly. “Why help when I know you don’t even like me?“

Priya looked up from her laptop, fatigue softening her carefully maintained composure. “Because it was the right thing to do.”

“I feel like I know you,” he said suddenly. “Like we’ve met before.”

Her fingers stilled on the keyboard. “We have.”

“When? I would remember…“

“Would you?” Her voice was soft, almost sad. “National University of Singapore. Computer Science. Professor Tan’s Advanced Programming module.”

The pieces clicked into place with sickening clarity. The Science canteen coffee shop. The project partner he’d barely acknowledged. The girl whose name he’d never bothered to learn.

“Oh God. Priya. You’re…“

“The same person I always was.” She closed her laptop with a quiet snap. “Just visible now.”

Marcus felt like the floor had dropped away. “I was such an asshole.“

“You were twenty.” Her voice was matter-of-fact. “We all were someone different then.”

“No, I was worse than that. I was blind. I was…“

“You were a product of your environment.” Priya stood, gathering her things. “But that doesn’t mean I have to forget.”

She paused at the door. “The crisis is handled. I’ll have my legal team finalise the partnership documents. We don’t need to work together directly anymore.”

Marcus sat alone in the conference room as the sun rose over Singapore’s skyline, finally understanding why her eyes had seemed to see straight through him. She’d been measuring him against the boy who had looked right through her, and he’d been found wanting.

The question was: what was he going to do about it?

Marcus started small. He learned the names of everyone in his building: security guards, cleaning staff, and the uncle who ran the kopi tiam on the ground floor. He instituted monthly team meetings where junior associates could present ideas directly to leadership. He volunteered to mentor students at NUS, particularly those on financial assistance.

But mostly, he tried to become worthy of a second chance he wasn’t sure he’d ever get.

Two months later, he ran into Priya at a tech industry charity gala at the ArtScience Museum. She looked stunning in a midnight blue cheongsam, commanding attention in a room full of Singapore’s most influential people. Marcus approached carefully, his heart hammering.

“Priya.”

She turned, and for the first time since their reunion, her expression wasn’t guarded. “Marcus. I heard about your mentorship program.“

“Word travels fast in Singapore.”

“I fund three scholarships at NUS. I hear things.” She studied his face. “Why?”

“Because I finally realised that the world doesn’t revolve around people like me. And I wanted to do something useful with that realisation.”

They talked for an hour. Really talked. About their work, their families, their hopes for Singapore’s tech scene. When the evening ended, Marcus found the courage to ask again.

“Dinner? Not as a business meeting. As… whatever you’re comfortable with.”

Priya was quiet for so long, he thought she’d say no. Then: “There’s a place I like in Chinatown. Nothing fancy.“

“Perfect.”

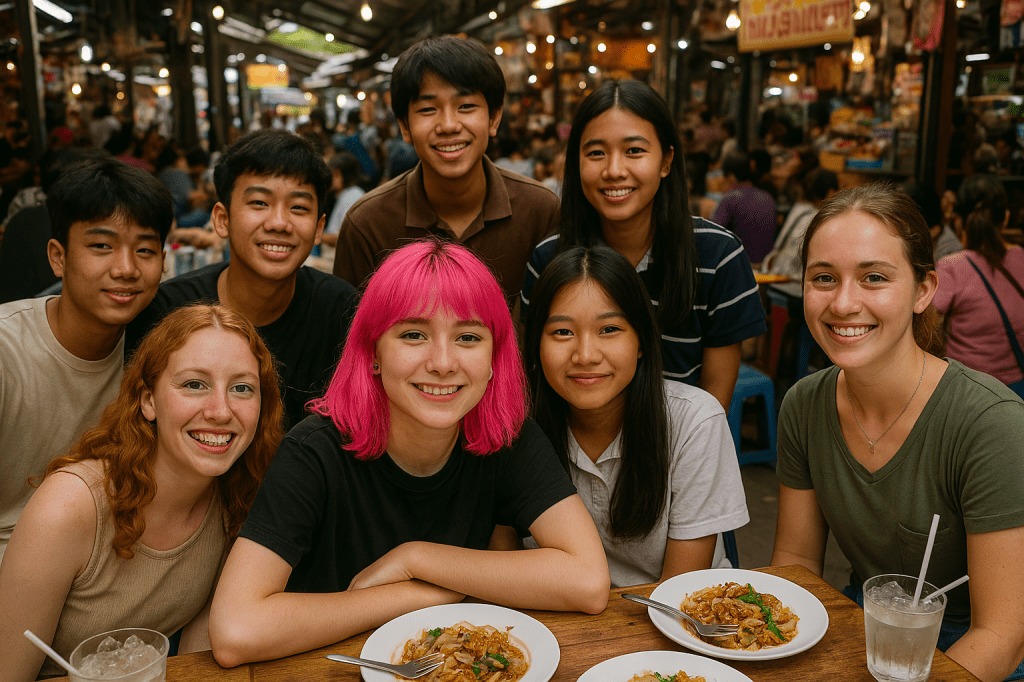

The restaurant was a hole-in-the-wall zi char stall tucked away in a back alley near Tanjong Pagar, with plastic chairs and the kind of authentic Hokkien food that couldn’t be found in trendy Clarke Quay establishments. Priya had changed into jeans and a simple blouse, and Marcus had never seen her look more beautiful.

“I used to come here during university,” she said, expertly manoeuvring her chopsticks around the sweet and sour pork. “It was the only place I could afford that felt special.”

“What was it like?” Marcus asked quietly. “Uni, I mean. For you.”

Priya considered the question. “Lonely, mostly. I was so focused on survival, academically and financially, that I forgot to be young. I watched people like you having experiences I couldn’t afford, and I told myself I didn’t want them anyway.”

“I’m sorry I was part of that.”

“You weren’t cruel, Marcus. You just… existed in a different world. One where people like me didn’t matter.”

“They did matter. I was just too stupid and self-absorbed to see it.”

She smiled then, the first genuine smile she’d given him. “We were both different people then.”

“I’d like you to know the person I am now.”

“I think,” Priya said slowly, “I’d like that too.”

Their courtship was careful, deliberate. Marcus learned that Priya had built her company not just from ambition, but from a desire to create opportunities for people who’d been overlooked the way she had been. She’d hired dozens of first-generation university graduates, funded coding bootcamps in heartland communities, and quietly revolutionised the way Singapore’s tech industry thought about talent.

Priya learned that Marcus’s newfound awareness wasn’t performative. He’d restructured his company’s hiring practices, implemented blind resume reviews, and somehow managed to do it all without seeking credit or recognition.

“You’ve changed,” she told him one evening as they walked along the Marina Barrage, the city lights reflecting off the reservoir, six months into whatever they were calling their relationship.

“Not changed,” Marcus said. “Just finally became who I was supposed to be.”

“And who is that?“

He stopped walking and turned to face her. “Someone worthy of you.”

Priya’s breath caught. In the glow of the Singapore skyline, she could see the boy he’d been in the man he’d become, but this version was better, deeper, marked by empathy and genuine humility.

“I was so angry for so long,” she whispered. “At you, at everyone who made me feel invisible. I built my whole life around never being that powerless again.”

“You were never powerless, Priya. You were just surrounded by people too blind to see your strength.”

When he kissed her, it tasted like forgiveness and possibility and the kind of love that comes from truly seeing another person.

One year later

The engagement party was held at the same conference room where they’d reconnected; Priya’s idea and characteristically perfect. Their two worlds had blended seamlessly: his family’s Peranakan heritage mixing with her chosen family of employees, mentees, and the professors who’d believed in her when no one else had. The catering was a mix of their favourites, from high-end hotel fare to zi char dishes that reminded them of their roots.

Marcus found Priya on the outdoor terrace, looking out over the glittering lights of the Marina Bay area.

“Having second thoughts?” he asked, wrapping his arms around her from behind.

“About marrying you? Never.” She leaned into him. “I was just thinking about that girl in the Science canteen. How she never could have imagined this moment.”

“She deserved it even then.”

“Maybe. But she wasn’t ready for it then. Neither of us were.”

Marcus turned her in his arms. “And now?”

Priya smiled, the expression transforming her face with joy. “Now we’re exactly who we’re supposed to be.”

As they kissed under the stars, the Singapore skyline sprawling endlessly below them, it felt like the best kind of second chance; not a revision of the past, but a bold new story written by two people who had finally learned how to truly see each other.

Some love stories begin with love at first sight. The best ones, perhaps, begin with sight at first love, the moment when two people finally become visible to each other, not as they were, but as they chose to become.