On September 18th each year, the world observes International Equal Pay Day – a day dedicated to raising awareness about the persistent gender pay gap and advocating for equal compensation regardless of gender. This important observance highlights the ongoing struggle for wage equality and serves as a call to action for governments, businesses, and individuals to address pay discrimination and create more equitable workplaces.

The gender pay gap remains a pervasive issue globally, with women on average earning less than men for work of equal value across nearly all industries and occupations. International Equal Pay Day shines a spotlight on this inequality and aims to accelerate progress towards achieving equal pay for work of equal value.

Equal pay for equal work is a fundamental human right and a cornerstone of gender equality. When women are paid less than men for the same work, it perpetuates gender discrimination and has far-reaching negative impacts on individuals, families, communities, and entire economies.

At its core, equal pay is about basic fairness and economic justice. When women are paid less for the same work, it devalues their contributions and sends the message that their labour is worth less. This violates the principle of equal pay for equal work and undermines notions of meritocracy and fair compensation. Paying women equally is simply the right thing to do from an ethical standpoint.

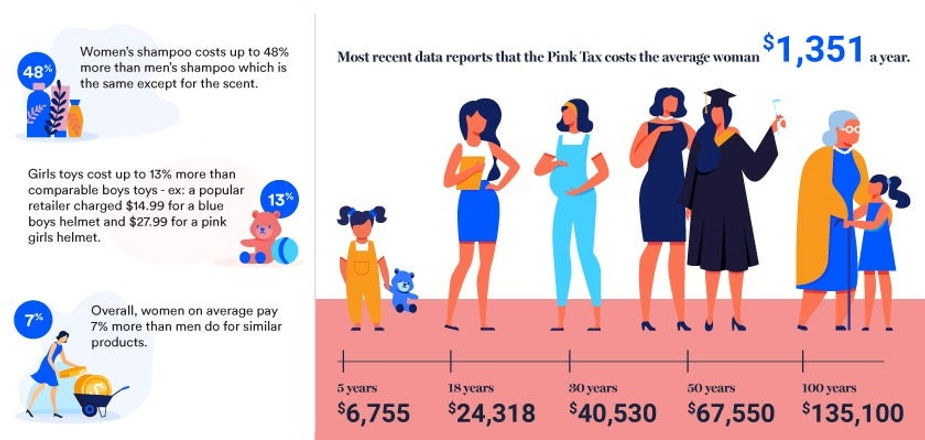

The gender pay gap contributes significantly to poverty rates among women and families. When women earn less, it reduces household incomes and makes it harder for families to make ends meet. Equal pay would boost incomes for women and families, helping to lift many out of poverty. This in turn improves quality of life, access to resources, and overall family well-being.

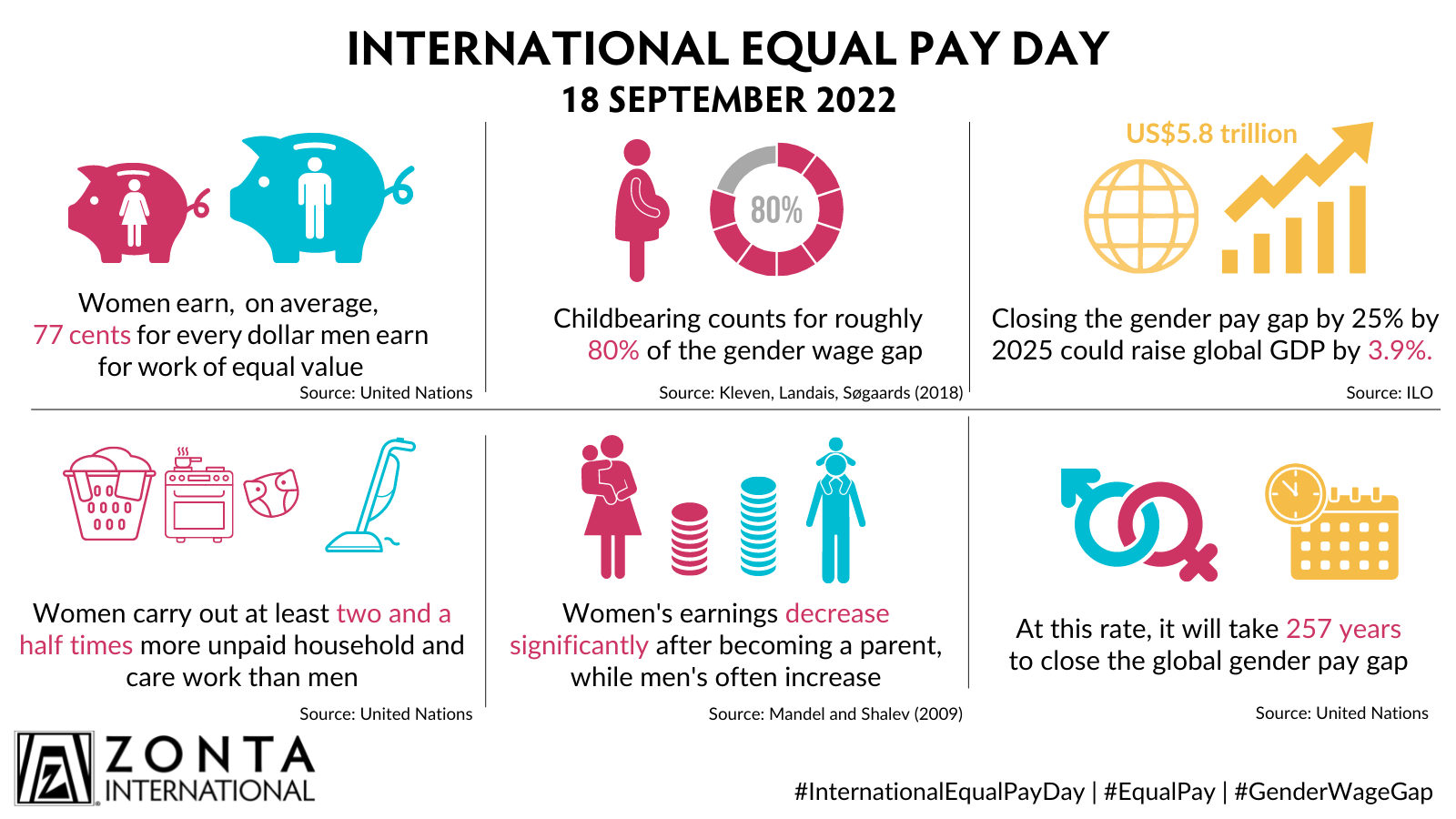

Closing the gender pay gap would provide a major boost to the global economy. When women have more income, they tend to spend more on goods and services, stimulating economic activity and growth. Some estimates suggest that achieving pay equity could add trillions of dollars to the global GDP. Pay equality allows economies to benefit from women’s full economic participation and purchasing power.

Research shows that companies with greater gender diversity and pay equity tend to outperform their less equitable peers. Equal pay helps businesses attract and retain top female talent, reduce turnover, increase productivity and innovation, and improve company reputation. Pay equity is increasingly seen as a competitive advantage for forward-thinking businesses.

The pay gap is both a cause and a consequence of broader gender inequalities in society. Closing the pay gap helps break down gender stereotypes, challenges occupational segregation, and creates more opportunities for women’s advancement. Equal pay is a crucial step towards achieving overall gender equality across social, political, and economic spheres.

When women earn less over their lifetimes due to the pay gap, it reduces their long-term economic security and increases their risk of poverty in old age. Equal pay allows women to accrue more savings, build greater wealth, and have more resources for retirement. This enhances women’s financial independence and security throughout their lives.

Achieving equal pay sends a powerful message to girls and young women that their work is equally valued and that they can aspire to any career. It helps break intergenerational cycles of inequality and creates more opportunities for the next generation. Equal pay sets an important precedent of fairness and equality for youth.

The date of September 18th for International Equal Pay Day was chosen deliberately to highlight how far into the year women must work to earn what men earned in the previous year. In other words, it symbolically represents the extra days women must work to catch up to men’s earnings. The September 18th date is based on global estimates that women earn on average about 77% of what men earn for work of equal value. This translates to a pay gap of about 23%. Mathematically, women would need to work about 70 extra days into the new year, or until September 18th to make up this 23% difference.

The specific date may vary slightly from year to year and differs in various countries based on their pay gaps. However, September 18th was chosen as a representative global date to create a unified day of awareness and action.

The September 18th date occurs near the end of the year to emphasise how long women must work to catch up. It falls on a weekday to highlight the issue in the context of the regular workweek. It’s after most schools are back in session, allowing for educational events. It avoids major holidays or national observances in most countries. The date provides time after summer vacations for organising awareness activities

By choosing a date that viscerally demonstrates the tangible impact of the pay gap, International Equal Pay Day aims to create a sense of urgency around addressing this persistent inequality. The September 18th observance serves as a powerful reminder that women are still playing catch-up when it comes to compensation.

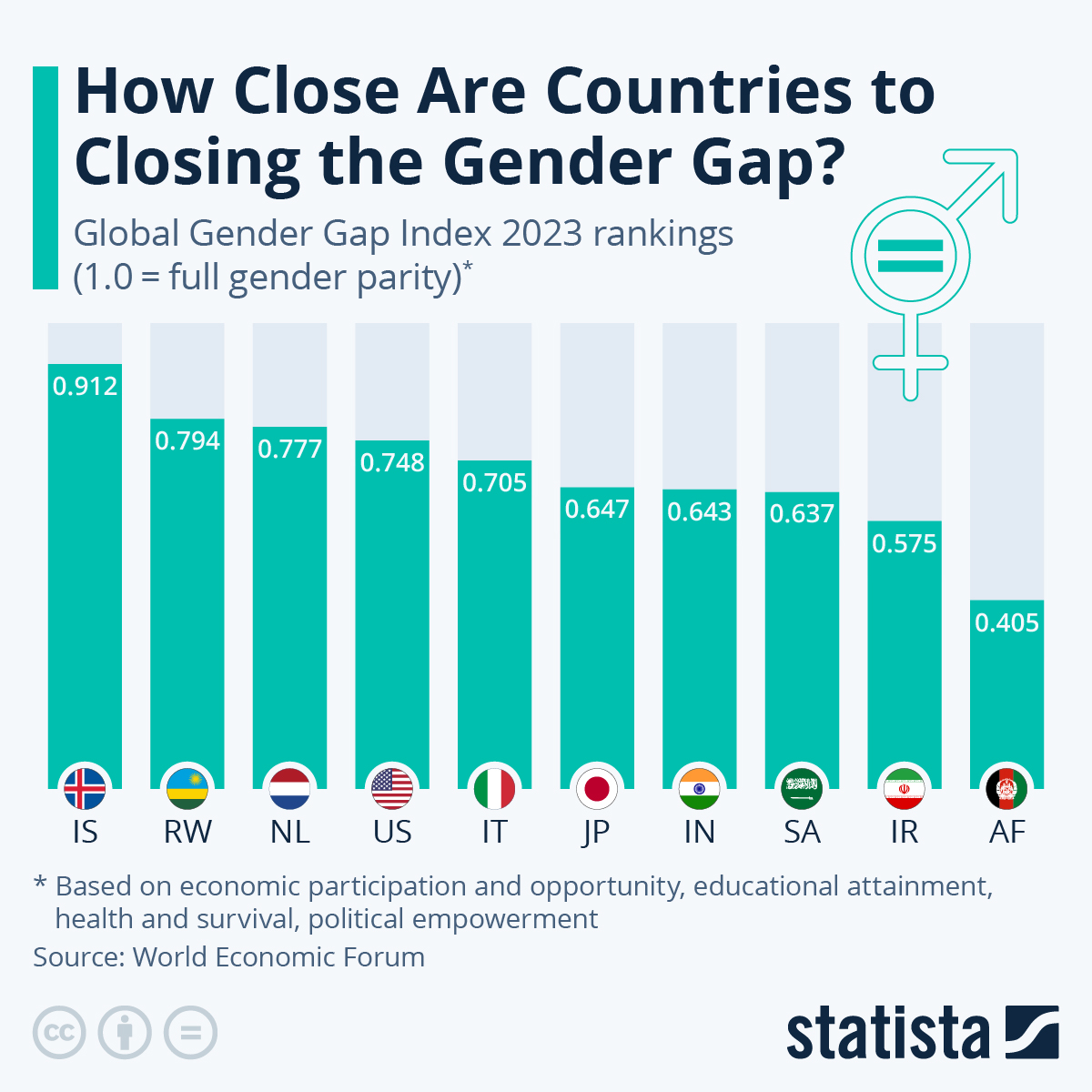

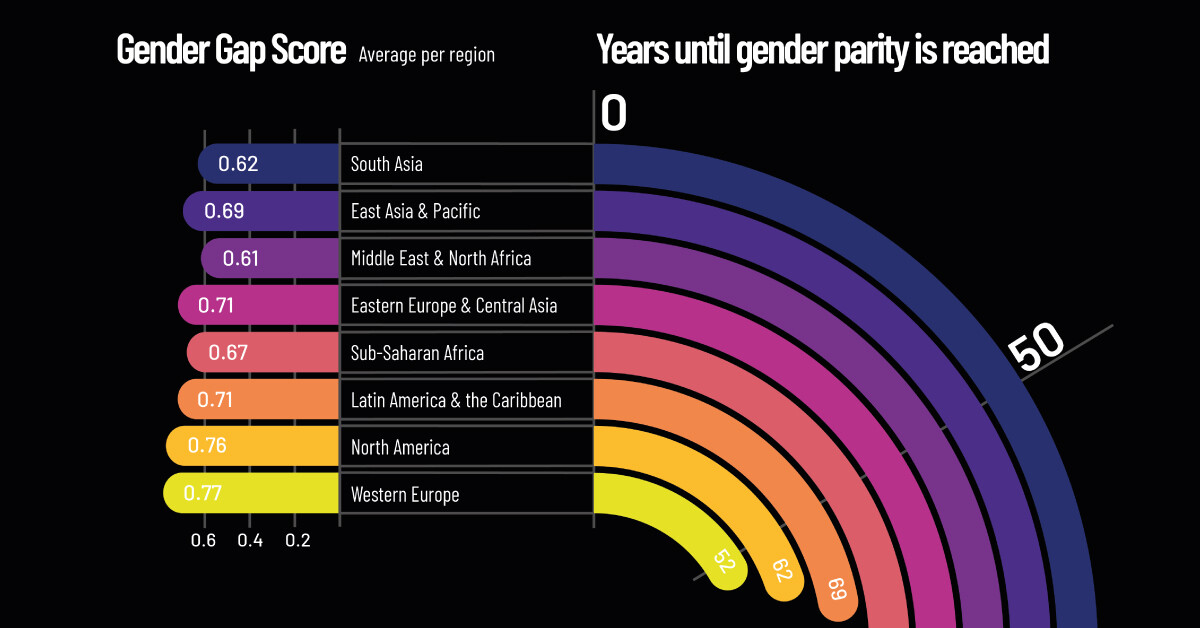

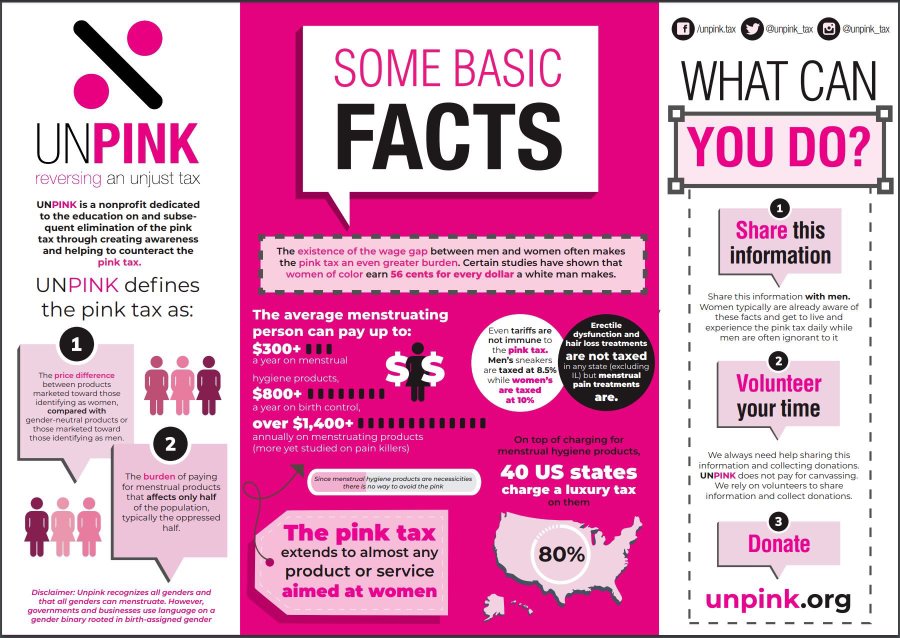

While progress has been made in recent decades towards narrowing the gender pay gap, significant disparities persist around the world. Worldwide, women earn on average 77% of what men earn for work of equal value. The global gender pay gap is estimated at 23%. At the current rate of progress, it will take 257 years to close the global gender pay gap. The pay gap tends to be smallest in countries with strong equal pay laws and social policies. Scandinavian countries like Iceland and Norway have some of the smallest pay gaps while the gap tends to be larger in developing countries and regions with weaker labour protections. The pay gap is often wider for women of colour, immigrant women, and other marginalised groups. Factors like race, ethnicity, age, disability status, and sexual orientation intersect with gender to impact pay. An intersectional approach is needed to address pay inequalities faced by diverse groups of women.

Women are overrepresented in lower-paying occupations and underrepresented in higher-paying fields. Even in female-dominated occupations, men tend to earn more and advance faster. Increasing women’s access to male-dominated, higher-paying fields is key to closing the gap. Women often face a “motherhood penalty” in pay and career advancement after having children. The pay gap tends to widen for women after becoming mothers. Better parental leave and childcare policies are needed to address this.

Women are underrepresented in senior leadership and high-paying executive roles. The pay gap tends to be largest at the top of the wage distribution. Getting more women into leadership positions is crucial for pay equity. While the numbers vary by country and context, the overall picture shows that the gender pay gap remains a persistent global challenge requiring continued focus and action. International Equal Pay Day serves as an important reminder of how much work remains to be done.

To effectively address the pay gap, it’s important to understand its complex root causes. The gender pay gap stems from a variety of interrelated factors. Despite laws against pay discrimination, both conscious and unconscious biases continue to impact hiring, promotion, and compensation decisions. Stereotypes about women’s capabilities and commitment can lead to lower starting salaries and fewer opportunities for advancement. Women are overrepresented in lower-paying fields and underrepresented in higher-paying STEM and leadership roles. This occupational segregation is influenced by societal expectations, education disparities, and discrimination.

Women still shoulder a disproportionate share of unpaid care work for children and family members. This can lead to career interruptions, reduced hours, and missed opportunities for advancement that impact long-term earnings. When pay information is not transparent, it’s harder to identify and address gender-based pay disparities. Secrecy around compensation allows pay discrimination to persist unchallenged. Research shows women are less likely to negotiate salaries and raises, and face backlash when they do. This can lead to lower starting salaries that compound over time.

Women are more likely to work part-time, often due to caregiving duties. Part-time work tends to pay less per hour and offers fewer opportunities for advancement. While women have made great strides in educational attainment, gaps remain in some fields. Limited access to training and professional development can also hinder women’s career progression. Jobs traditionally associated with women, like teaching and caregiving, tend to be paid less than male-dominated professions requiring similar skills and education.

With fewer women in senior decision-making roles, there are limited champions for pay equity initiatives and role models for aspiring female leaders. Weak or poorly enforced equal pay laws, along with limited paid leave and childcare support, create an environment where the pay gap can persist. Understanding these multifaceted root causes is essential for developing comprehensive solutions to close the gender pay gap. Effective strategies must address both individual factors and broader systemic issues.

Closing the gender pay gap requires a multifaceted approach involving governments, employers, and individuals.

What governments can do is strengthen and enforce equal pay laws, mandate pay transparency and reporting, implement comprehensive paid family leave policies, invest in affordable, high-quality childcare, promote women’s education and training in high-paying fields, set targets for women’s representation in leadership roles, and raise the minimum wage and improve protections for part-time workers.

Actions that employers can take include conducting regular pay equity audits and addressing any disparities, implementing transparent pay scales and job evaluation systems, training managers on unconscious bias in hiring and promotion decisions, offering flexible work arrangements to support work-life balance, actively recruiting and promoting women into leadership positions, providing mentorship and sponsorship programmes for women, and offering paid parental leave and supporting returning parents

As an individual, one should educate oneself about the pay gap and one’s rights, research salary information and negotiate fair compensation, support and mentor other women in the workplace, join or form employee resource groups focused on gender equity, advocate for pay transparency and equity initiatives at one’s workplace, challenge gender stereotypes and biases when one encounters them, and share caregiving responsibilities more equally in one’s household.

Collectively, we should support organisations working to close the pay gap, participate in Equal Pay Day awareness events and campaigns, advocate for policy changes with elected officials, boycott companies with poor track records on pay equity, use social media to raise awareness about the pay gap, encourage men to be allies in the fight for pay equity, and join unions or professional associations advocating for fair pay.

By taking action at multiple levels – from government policies to workplace practices to individual behaviours – we can accelerate progress towards closing the gender pay gap. Every step, no matter how small, contributes to creating a more equitable world.

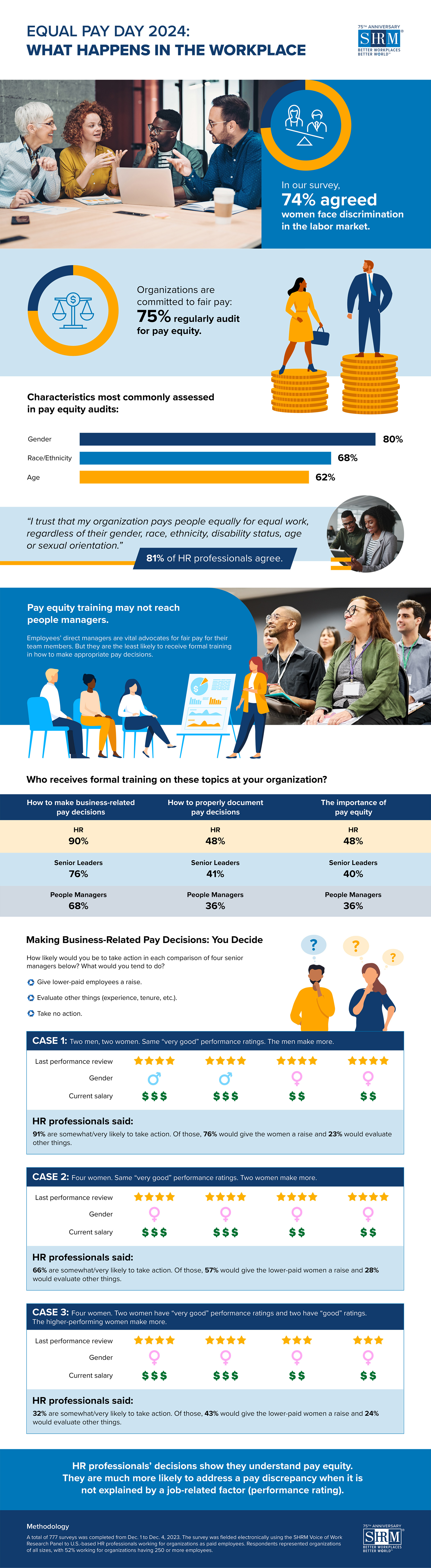

Data and transparency play a crucial role in identifying, understanding, and addressing the gender pay gap. Without accurate information on compensation across genders, it’s difficult to pinpoint where disparities exist and take targeted action to close them. Comprehensive pay data allows organisations to identify where gender-based pay gaps exist within their workforce. This data can reveal patterns across departments, job levels, and demographic groups. Regular collection and analysis of pay data enables tracking of progress over time. This allows organisations and policymakers to assess the effectiveness of various initiatives and adjust strategies as needed. Robust data on the pay gap informs the development of evidence-based policies at both the organizational and governmental levels. It helps policymakers understand the scope of the problem and design targeted interventions.

Transparent reporting of pay gap data raises awareness among employees, stakeholders, and the public. This increased visibility can create pressure for change and hold organizations accountable. When employees have access to pay information, they are better equipped to negotiate fair compensation and challenge discriminatory practices. Transparency reduces information asymmetry in salary negotiations. Public reporting of pay data allows for benchmarking and identification of best practices. Organisations can learn from peers who have successfully narrowed their pay gaps.

In many jurisdictions, pay data reporting is becoming a legal requirement. Transparency initiatives help organisations stay compliant with evolving equal pay laws. Openness about pay practices demonstrates a commitment to fairness and can build trust with employees, customers, and investors. It shows that an organization has nothing to hide.

To leverage the power of data and transparency, organizations and governments should conduct regular pay equity audits, implement pay transparency policies, publicly report gender pay gap data, use standardised metrics for consistent reporting, analyse intersectional data to understand disparities among different groups, invest in data collection and analysis capabilities, and foster a culture of openness around compensation. By embracing data and transparency, we can shine a light on pay disparities and create the accountability needed to drive real change.

While closing the gender pay gap is fundamentally about fairness and equality, there is also a strong business case for pay equity. Companies that prioritise fair compensation regardless of gender often see significant benefits. Organisations known for pay equity are better positioned to attract and retain top talent, particularly women, who are increasingly prioritising fair pay when choosing employers. When employees feel they are compensated fairly, they tend to be more engaged, motivated, and productive. Pay equity contributes to a positive workplace culture. Diverse teams with equitable pay practices tend to be more innovative and creative, bringing a wider range of perspectives to problem-solving.

Companies that demonstrate a commitment to pay equity often enjoy improved reputations among customers, investors, and the general public. This can translate into brand loyalty and increased market share. Proactively addressing pay equity reduces the risk of costly discrimination lawsuits and regulatory penalties. It’s often more cost-effective to address disparities early than to face legal challenges later. Research suggests that companies with greater gender diversity and pay equity tend to outperform their less equitable peers financially. Pay equity can contribute to stronger bottom-line results.

When women are fairly compensated and represented at all levels of an organization, it leads to more balanced and effective decision-making. Many investors now consider gender pay equity as part of their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria. Companies with strong pay equity practices may be more attractive to socially conscious investors. For companies serving diverse customer bases, pay equity helps ensure the workforce better reflects and understands its customers, leading to improved products and services.

As pay equity becomes increasingly important to employees, customers, and regulators, companies that address it now will be better positioned for future success. By recognising and leveraging these business benefits, companies can align their financial interests with the ethical imperative of pay equity. This creates a win-win situation where doing the right thing also drives business success.

International Equal Pay Day serves as a powerful reminder of the ongoing struggle for wage equality and the importance of closing the gender pay gap. While progress has been made, significant disparities persist, requiring continued focus and action from governments, employers, and individuals.

The reasons for prioritising equal pay are compelling – from basic fairness and economic justice to improved business performance and accelerated economic growth. By addressing the root causes of the pay gap and implementing comprehensive solutions, we can create more equitable workplaces and societies.

As we commemorate International Equal Pay Day on September 18th, let it serve not just as a day of awareness, but as a call to action. Every person has a role to play in advancing pay equity, whether through advocating for policy changes, implementing fair practices in the workplace, or challenging biases in our daily lives.

Closing the gender pay gap is not just about numbers on a paycheck – it’s about valuing women’s contributions equally, creating opportunities for advancement, and building a more just and prosperous world for all. As we strive for wage equality, we move closer to realizing the full potential of half the world’s population.