Kathmandu

The seat of the federal government and Nepal’s most populous city, Kathmandu is also the capital of Nepal. It is located in the Kathmandu Valley, a large valley surrounded by hills in the high plateaus in central Nepal, at an altitude of 1,400 m.

The city is one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in the world, founded in the 2nd century AD. The valley was historically called the ‘Nepal Mandala’ and has been the home of the Newar people. The city was the royal capital of the Kingdom of Nepal and has been home to the headquarters of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) since 1985. Today, it is the seat of government of the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal, established in 2008, and is part of Bagmati Province.

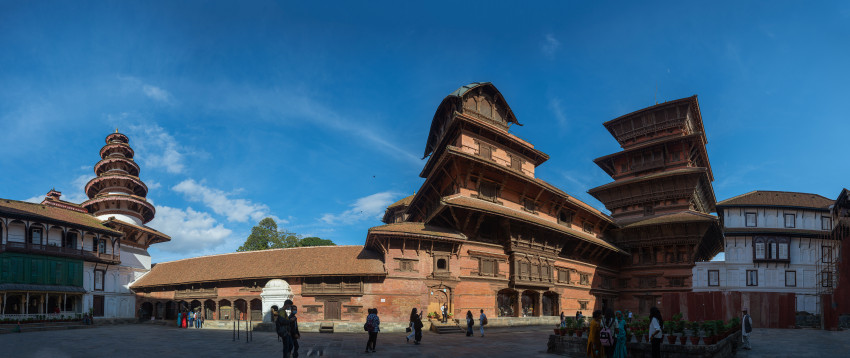

Kathmandu is and has been for many years the centre of Nepal’s history, art, culture, and economy. It has a multi-ethnic population within a Hindu and Buddhist majority. Tourism is an important part of the economy in the city. The city is considered the gateway to the Nepal Himalayas and is home to several World Heritage Sites: the Durbar Square, Swayambhu Mahachaitya, Bouddha and Pashupatinath.

The indigenous Nepal Bhasa term for Kathmandu is Yen. The Nepali name Kathmandu comes from Kasthamandap, a building that stood in Kathmandu Durbar Square and was completely destroyed by the April 2015 Nepal Earthquake. The building has since been reconstructed. In Sanskrit, Kāṣṭha means wood and Maṇḍapa means pavilion. This public pavilion, also known as Maru Satta in Newari, was rebuilt in 1596 by Biseth in the period of King Laxmi Narsingh Malla. The three-storey structure was made entirely of wood and used no iron nails nor supports. According to legend, all the timber used to build the pagoda was obtained from a single tree. The city is called Kāṣṭhamaṇḍap in a vow that Buddhist priests still recite to this day. During medieval times, the city was sometimes called Kāntipur, which is derived from two Sanskrit words – Kānti meaning beauty and Pur meaning a place which gives the city the name meaning city of light.

Among the indigenous Newar people, Kathmandu is known as Yeṃ Dey, and Patan and Bhaktapur are known as Yala Dey and Khwopa Dey respectively. Yem is the shorter form of Yambu, which originally referred to the northern half of Kathmandu. The older northern settlements were referred to as Yambi while the southern settlement was known as Yangala. Archaeological excavations in parts of Kathmandu have found evidence of ancient civilisations. The oldest of these findings is a statue, found in Maligaon, that was dated at 185 AD.

According to the Swayambhu Purana, present-day Kathmandu was once a huge and deep lake named Nagdaha, as it was full of snakes. The lake was cut drained by Bodhisattva Manjushri with his sword, and the water was evacuated out from there. He then established a city called Manjupattan, and made Dharmakar the ruler of the valley land. After some time, a demon named Banasura closed the outlet, and the valley again turned into a lake. Krishna came to Nepal, killed Banasura, and again drained out the water by cutting the edge of Chobhar hill with this Sudarshana Chakra. He brought some cowherds along with him and made Bhuktaman the king of Nepal. Kotirudra Samhita of Shiva Purana, Chapter 11, Shloka 18 refers to the place as Nayapala city, which was famous for its Pashupati Shivalinga. The name Nepal probably originates from this city Nayapala.

The Licchavis from Vaisali in modern-day Bihar, migrated north and defeated the Kirats, establishing the Licchavi dynasty, circa 400 AD. During this era, following the genocide of Shakyas in Lumbini by Virudhaka, the survivors migrated north and entered the forest monastery, masquerading as Koliyas. From Sankhu, they migrated to Yambu and Yengal or Lanjagwal and Manjupattan and established the first permanent Buddhist monasteries of Kathmandu. This created the basis of Newar Buddhism, which is the only surviving Sanskrit-based Buddhist tradition in the world. With their migration, Yambu was called Koligram and Yengal was called Dakshin Koligram during most of the Licchavi era. Eventually, the Licchavi ruler Gunakamadeva merged Koligram and Dakshin Koligram, founding the city of Kathmandu.

The city was designed in the shape of Chandrahrasa, the sword of Manjushri, surrounded by eight barracks guarded by Ajimas. One of these barracks is still in use at Bhadrakali, in front of Singha Durbar. The city served as an important transit point in the trade between India and Tibet, leading to tremendous growth in architecture.

The Licchavi era was followed by the Malla era. Rulers from Tirhut, upon being attacked by the Delhi Sultanate, fled north to the Kathmandu valley. They intermarried with Nepali royalty, and this led to the Malla era. The devastating earthquake which claimed the lives of a third of Kathmandu’s population led to the destruction of most of the architecture of the Licchavi era and the loss of literature collected in various monasteries within the city. Despite the initial hardships, Kathmandu rose to prominence again and, during most of the Malla era, dominated the trade between India and Tibet and the Nepali currency became the standard currency in trans-Himalayan trade. During the later part of the Malla era, Kathmandu Valley comprised four fortified cities: Kantipur, Lalitpur, Bhaktapur, and Kirtipur. These served as the capitals of the Malla confederation of Nepal and competed with each other in the arts, architecture, esthetics, and trade, resulting in tremendous development.

The Gorkha Kingdom ended the Malla confederation after the Battle of Kathmandu in 1768. This marked the beginning of the modern era in Kathmandu. The Battle of Kirtipur was the start of the Gorkha conquest of the Kathmandu Valley. Kathmandu was adopted as the capital of the Gorkha empire, and the empire itself was dubbed Nepal. During the early part of this era, Kathmandu maintained its distinctive culture. The Rana rule over Nepal started with the Kot massacre of 1846. During this massacre, most of Nepal’s high-ranking officials were massacred by Jung Bahadur Rana and his supporters. Another massacre, the Bhandarkhal Massacre, was also conducted by Kunwar and his supporters in Kathmandu. During the Rana regime, Kathmandu’s alliance shifted from anti-British to pro-British; leading to the construction of the first buildings in the style of Western European architecture. The Rana rule was marked by despotism, economic exploitation and religious persecution.

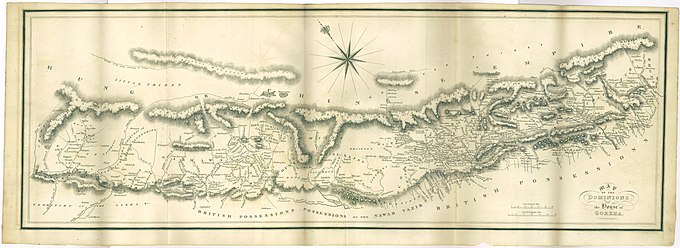

Located in the northwestern part of the Kathmandu Valley to the north of the Bagmati River, Kathmandu covers an area of 50.7 sq km with an average elevation of 1,400 m. The city is bounded by several other municipalities of the Kathmandu valley: south of the Bagmati by Lalitpur Metropolitan City or Patan, with which it forms one urban area surrounded by a ring road, to the southwest by Kirtipur and to the east by Madyapur Thimi. To the north the urban area extends into several municipalities; Nagarjun, Tarakeshwor, Tokha, Budhanilkantha, Gokarneshwor and Kageshwori Manohara. However, the urban agglomeration extends well beyond the neighbouring municipalities, and nearly covers the entire Kathmandu Valley.

Kathmandu is dissected by eight rivers, the main river of the valley, the Bagmati and its tributaries, of which the Bishnumati, Dhobi Khola, Manohara Khola, Hanumante Khola, and Tukucha Khola are predominant. The mountains from where these rivers originate have passes which provide access to and from Kathmandu and its valley. The ancient trade route between India and Tibet that passed through Kathmandu enabled a fusion of artistic and architectural traditions from other cultures to be amalgamated with local art and architecture. The monuments of Kathmandu City have been influenced over the centuries by Hindu and Buddhist religious practices. The architectural treasure of the Kathmandu valley has been categorised under the well-known seven groups of heritage monuments and buildings which in 2006 was declared as World Heritage Sites by UNESCO.

Pashupatinath Temple is a famous 5th century Hindu temple dedicated to Lord Shiva. Located on the banks of the Bagmati River, Pashupatinath Temple is the oldest Hindu temple in Kathmandu and served as the seat of the national deity, Pashupatinath, until Nepal was secularised. A significant part of the temple was destroyed by Mughal invaders in the 14th century and little or nothing remains of the original 5th-century temple exterior. The temple as it stands today was built in the 19th century, although the image of the bull and the black four-headed image of Pashupati are at least 300 years old. The temple complex consists of 518 small temples and a main pagoda house. It is believed that the Jyotirlinga housed in the Pashupatinath temple is the head of the body, which is made up of the twelve Jyotirlinga in India. The temple was made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979 with Shivaratri, or the night of Shiva, the most important festival that takes place here, attracting thousands of devotees and holy men.

The temple stretches across both the banks of the beautiful and sacred Bagmati River on the eastern fringes of the capital city of Kathmandu. Only Hindus are allowed to enter the temple premises, non-Hindus are allowed to view the temple only from the across the Bagmati River. The priests who perform the services at this temple are Brahmins from Karnataka in southern India and have been serving the temple since the time of the Malla king Yaksha Malla. This tradition is believed to have been started at the request of Adi Shankara who sought to unify the states of Bhāratam, a region in south Asia believed to be ruled by a mythological king Bharata, by encouraging cultural exchange. This procedure is followed in other temples around India, which were sanctified by Adi Shankara.

The temple has four entrances in the four geographical directions. The main entrance is situated in the west and is the only one that is opened daily while the other three remain closed except during festival periods. Only Nepali practising Buddhists and practising Hindus are permitted to enter the temple courtyard. Practising Hindus who have descended from the west, along with other non-Hindu visitors, except Jain and Sikh communities with Indian ancestry, are not permitted to enter the temple complex. The others are allowed to have a glimpse of the main temple from the adjacent bank of the Bagmati River and are charged a nominal fee to visit the plethora of smaller temples that adorn the external premises of the Pashupatinath temple complex. No devotee is allowed to step into the innermost Garbhagriha. However, they are allowed to see the idol from the premises of the outer sanctum.

There are many legends that are attached to the Pashupatinath Temple. In the cow’s tale, Lord Shiva and Goddess Parvati once transformed themselves into antelopes and visited the dense forest on the eastern bank of the Bagmati River. Enamoured with the beauty of the place, Lord Shiva decided to stay back as a deer. The other deities soon came to know of this and pestered him to resume his divine form by gripping one of his horns, which broke in the process. This broken horn used to be worshipped as a Shivalinga but was buried and lost after a few years. Several centuries later, a herdsman found one of his cows showering milk on the site. Astonished, he dug deep into the site only to find the divine Shivalinga.

According to Gopalraj Aalok Vamsavali, the oldest chronicle of Nepal, the Pashupatinath Temple was constructed by Supushpa Deva, one of the Lichchavi rulers who ruled way before King Manadeva. Another story is that Pashupatinath Temple was already present in the form of a linga shaped Devalaya before Supushpa Deva’s arrival. He constructed a five-storey temple for Lord Shiva on that spot. As days rolled by, the necessity for the renovation of the holy shrine arose, before it was finally reconstructed by King Shivadeva. Later, King Ananta Malla added a roof to it.

The temple is built in the pagoda style of architecture, with cubic constructions and carved wooden rafters or tundals on which they rest, and two-level roofs made of copper and gold. The main complex of the temple is constructed in the Nepalese pagoda architectural style. The roof is made of copper and are gilded with gold, while the main doors are coated with silver. The main temple houses a gold pinnacle, known as Gajur, and two Garbhagrihas. While the inner garbhagriha is home to the idol of Lord Shiva, the outer area is an open space that resembles a corridor. The prime attraction of the temple complex is the sizable golden statue of Lord Shiva’s vehicle – Nandi the bull.

Bound with a serpent covered in silver, the prime deity is a Mukhalinga made of stone which rests upon a silver yoni base. The Shiva Lingam is one metre high and has four faces in four directions, each representing a different aspect of Lord Shiva, namely – Sadyojata or Varun, Tatpurusha, Aghora, and Vamadeva or Ardhanareeswara. Another imaginative face of Ishana is believed to point towards the zenith. Each face is said to represent the five primary elements, which include air, earth, ether, fire, and water. Tiny hands protrude out from each face and are shown to be holding a kamandalu in the left hand and a rudraksha mala in the right. The idol is decked in golden attire, or vastram.

The most extraordinary feature of the Pashupatinath Temple is that the main idol can be touched only by four priests. Two sets of priests carry out the daily rites and rituals in the temple, the first being the Bhandari and the second being the Bhatt priests. The Bhatt are the only ones who can touch the deity and perform the religious rites on the idol, while the Bhandaris are the caretakers of the temple.

The temple is usually full of the elderly who believe that those who die in the temple are reincarnated as human beings, and all the misconducts of their previous lives are forgiven. The temple is open from 9 to 11 am when all four doors of the temple are opened during the abhisheka time and is the only time when all the four faces of the Shiva Lingam are visible to devotees.

Visitors can purchase the basic abhishekam ticket from the counter at the entrance for NPR 1100. This covers various pujas including the Rudrabhisheka. The Abhisheka is performed depending on the direction from which the face of the deity is viewed. The temple is open from 4 am to 12 noon and then again between 5 to 9 pm. The inner courtyard is open between 4 am and 7 pm while the sanctum sanctorum is open during the temple opening hours. Apart from abhisheka time, devotees can worship from all the four entrances from 9:30 am to 1:30 pm. Entry is free for Indian and Nepali citizens while for foreigners and SAARC nationals, one needs to pay NPR 1000 per person. A guide will cost about NPR 1000 who will walk visitors through the temple complex and talk about the traditions and rituals of the Pashupatinath temple.

Budhanilkantha Temple is an open-air shrine located at the foothills of the Shivpuri Hill in Kathmandu Valley. It is dedicated to Lord Vishnu and houses an exceptional idol of the presiding deity seen in a reclining posture in a pool of water. It is the largest stone statue in Nepal. The temple attracts not just devotees but also tourists in large numbers, especially during the occasion of Haribondhini Ekadashi Mela, which is held annually on the 11th day of Kartik month of the Hindus, usually in October or November.

The name Budhanilkantha literally means ‘old blue throat’ and is believed to be sculpted during the reign of Vishnu Gupta, a monarch who served under the King of the valley of Kathmandu, King Bhimarjuna Dev, in the 7th century. It is believed the statue was discovered by a farmer and his wife while ploughing a field. As they were ploughing, they struck something and blood started oozing out of the ground. On digging further, they found a gigantic idol of Lord Vishnu. There’s also a legend about a curse of visiting the temple. King Pratap Malla is said to have had a vision which made him believe that the Kings would die if they visited the temple. Therefore, no King ruling Nepal ever visited this temple.

The idol has been reclining on Sheshnaag floating in a pool of water for years and is believed to be a miracle. After the mid-1900s, a small sample of the idol was tested and it was found that it is low-density silica-based stone with properties similar to the lava rock. The temple can be combined with a trip to the Shivpuri National Park. The Budhanilkantha Temple is open from 6 am to 6 p, and the morning rituals start at 7 am.

Once the royal palace of the Malla kings and the Shah dynasty, Hanuman Dhoka is a complex of ancient structures with some as old as mid 16th century. Located in the Darbar Square of Kathmandu, it is locally known as Hanuman Dhoka Darbar, the name of which is derived from an antique idol of Lord Hanuman near the main entrance of an ancient palace. ‘Dhoka’ which means door in the local language, Hanuman Dhoka is spread over 5 acres and was severely destroyed during the 2015 earthquake.

The entrance of the complex is located on the west end of the durbar and has an ancient statue of Lord Hanuman on the left side of the palace. Covered in orange gauze, it is believed that Lord Hanuman protects the palace. Every day, many devotees visit the statue to offer their prayers. The vermillion smeared statue is one of the oldest structures in the complex. Another statue right next to Lord Hanuman is that of Narasimha gorging on a demon Hiranyakashipu, built during the reign of King Pratap Malla. The outside of the palace has an inscription on a tablet made of stone. It is etched in fifteen different languages and is believed that if the inscriptions are read correctly, the tablet will ooze out milk.

The east side of Hanuman Dhoka houses the Nasal Chok Courtyard dedicated to Lord Shiva. King Birendra Bir Bikram Shah was crowned in this area of the complex in 1975. The courtyard has intricately carved wooden frames, doorways with carvings of Hindu deities, and beautiful windows. The door leads to the private chambers of King Malla and an audience chamber. A Maha Vishnu Temple once existed on this side of the complex which was destroyed in an earthquake in 1934. The eastern wall now bears a beautiful painting of Lord Vishnu in a verandah. One can check out the throne of King Malla and beautiful portraits of the Shah Kings here. This section also has a Panchmukhi Hanuman Temple and a nine-story tower called the Basantpur Tower.

A little ahead is the Mul Chowk which is dedicated to Goddess Taleju Bhawani. The Mallas were ardent believers of Goddess Taleju. This section has some shrines and is considered to be the best place to perform certain important rituals. The temple is located on the south of the courtyard and has a golden Torana or a door garland. As one enters, they would see several images of Goddesses Ganga and Yamuna before reaching the idol of the presiding Goddess inside the ancient triple-roofed structure.

The northern section of the palace has the Sundari and the Mohan Chok which are no longer open for the tourists. The Mohan Chok was the residential courtyard for the kings during the reign of the Malla Kings. In fact, only the princes born in this part of the palace were considered as an heir to the throne. This courtyard houses the Sun Dhara, a golden waterspout. The water is believed to have originated from Budhanilkantha and was, therefore, used by the Kings to perform ablutions. The section on the south-east of this courtyard is where one can find four watchtowers. These towers were built during the reign of the first Gorkha King, King Prithvi Narayan Shah in 1768. His royal family stayed at the palace till the late 1800s before relocating to the Narayanhiti Palace in Kathmandu.

Hanuman Dhoka houses museums where one can get a glimpse into the history and lifestyle of Nepali royalty. These are the Tribhuwan Museum, the King Mahendra Memorial Museum, the King Birendra Museum, and the Palace Museum. One can find exhibits of artefacts belonging to the king, from ancient coins, dazzling jewels, exquisite thrones, fascinating stone and woodwork, furniture, striking weapons, and intricate carvings from the temples. The museums also have recreations of the king’s personal quarters. A section of the grand museums also exhibits details about significant changes that have played a major role in charting its history. History buffs would find this place to be a rich source of information from the old times in Nepal. The museum is open from 10:30 am to 4:30 pm, Tuesdays to Saturdays and from 10:30 am to 2:30 pm on Sundays. Its is closed on Mondays. Entry fees are NPR 750 per person for foreigners and NPR 150 per person for SAARC Citizens

Lakshmi is a thirteen-year-old girl who lives with her family in a small hut on a mountain in Nepal. Though she is desperately poor, her life is full of simple pleasures, like playing hopscotch with her best friend from school, and having her mother brush her hair by the light of an oil lamp. But when the harsh Himalayan monsoons wash away all that remains of the family’s crops, Lakshmi’s stepfather says she must leave home and take a job to support her family.

Lakshmi is a thirteen-year-old girl who lives with her family in a small hut on a mountain in Nepal. Though she is desperately poor, her life is full of simple pleasures, like playing hopscotch with her best friend from school, and having her mother brush her hair by the light of an oil lamp. But when the harsh Himalayan monsoons wash away all that remains of the family’s crops, Lakshmi’s stepfather says she must leave home and take a job to support her family.