As with many of my writing inspirations, I came across the term Choice Overload in a book I was reading and it intrigued me enough to find out more. And when I did, I knew I had to write this piece and share it with you all.

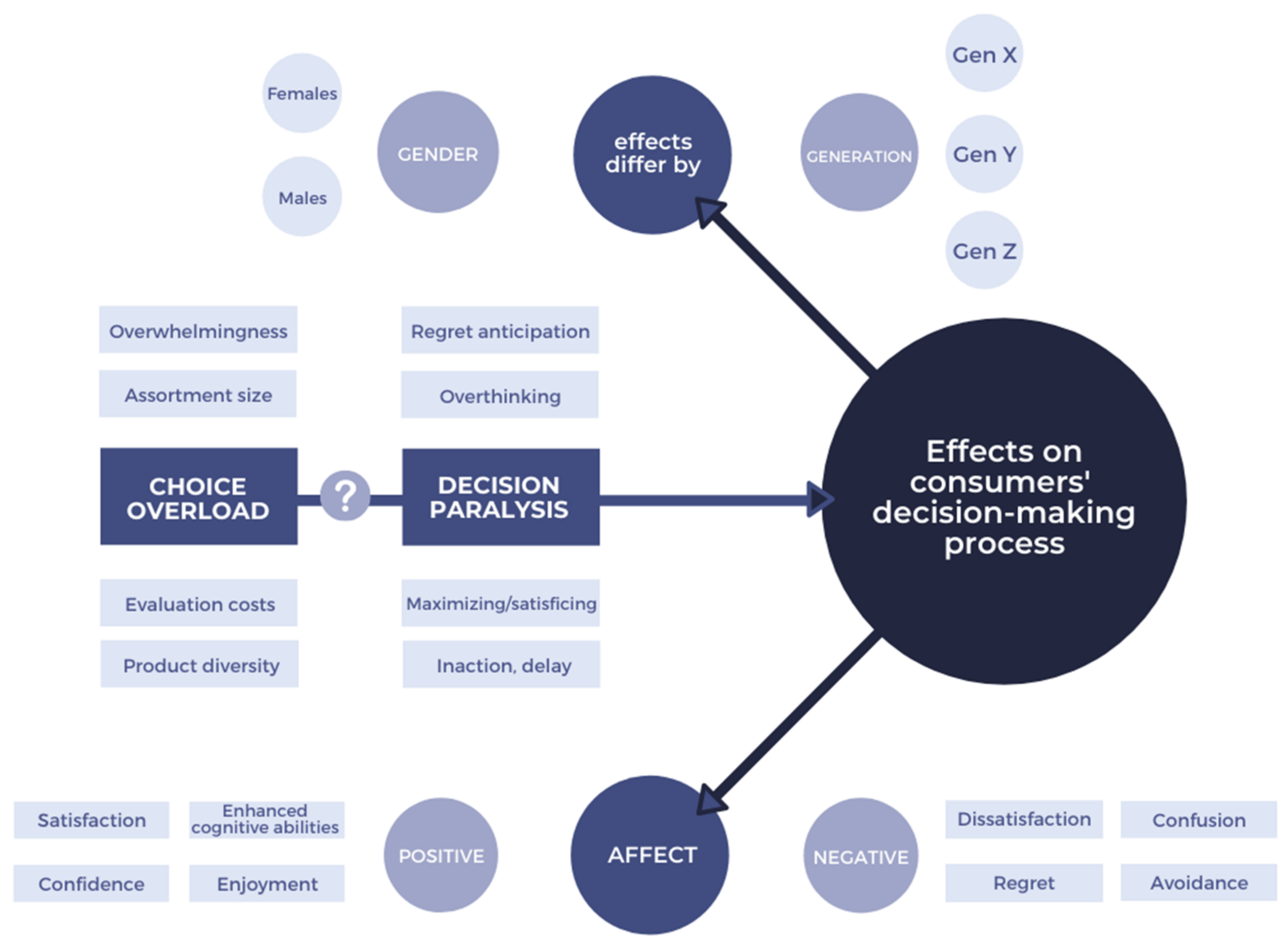

Choice overload or overchoice, choice paralysis or the paradox of choice is a cognitive impairment in which people have a difficult time making a decision when faced with many options. While we tend to assume that more choice is a good thing, in many cases, research has shown that we have a harder time choosing from a larger array of options.

The term was first introduced by Alvin Toffler in his 1970 book, Future Shock, but the phenomenon has come under some criticism due to increased scrutiny of scientific research related to the replication crisis and has not been adequately reproduced by subsequent research, thereby calling into question its validity.

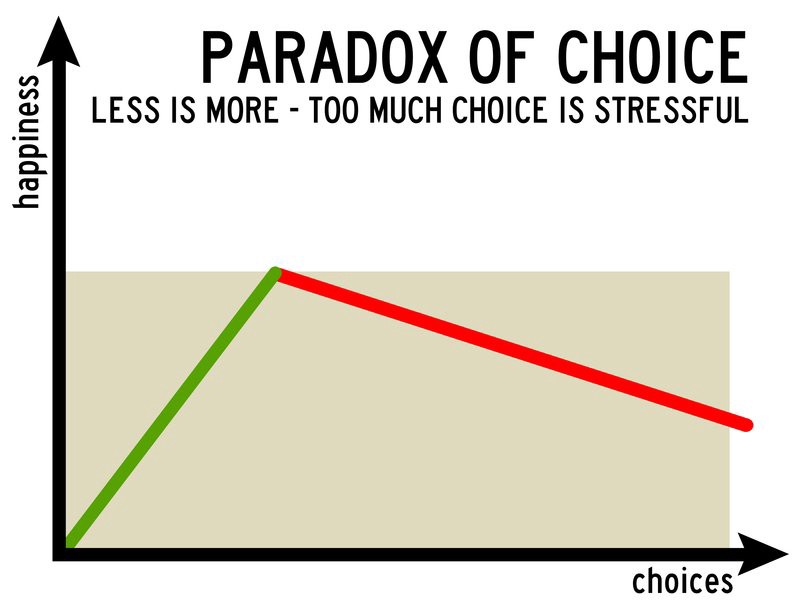

The phenomenon of choice overload or overchoice occurs when many equivalent choices are available and making a decision becomes overwhelming due to the many potential outcomes and risks that may result from making the wrong choice. Having too many approximately equally good options is mentally draining because each option must be weighed against alternatives to select the best one. The satisfaction of choices by many options available can be described by an inverted U model, where having no choice results in very low satisfaction. Initially, more choices lead to more satisfaction, but as the number of choices increases it then peaks and people tend to feel more pressure, confusion, and potentially dissatisfaction with their choice. Although larger choice sets can be initially appealing, smaller choice sets lead to increased satisfaction and reduced regret. Another component of overchoice is the perception of time. Extensive choice sets can seem even more difficult with a limited time constraint. Overchoice has been associated with unhappiness, decision fatigue, going with the default option, as well as choice deferral or avoiding making a decision altogether, such as not buying a product. Choice overload can be counteracted by simplifying choice attributes or the number of available options. However, some studies on consumer products suggest that, paradoxically, the greater choice should be offered in product domains in which people tend to feel ignorant like wine, whereas less choice should be provided in domains in which people tend to feel knowledgeable like soft drinks. Many of the increased options in our lives can be attributed to modern technology as in today’s society we have easy access to more information, products and opportunities.

Choice overload is not a problem in all cases, some preconditions must be met before the effect can take place. First, people making the choice must not have a clear prior preference for an item type or category. When the choice-maker has a preference, the number of options has little impact on the final decision and satisfaction. Second, there must not be a dominant option in the choice set, meaning that all options must be perceived of equivalent quality. One option cannot stand out as being better than the rest. The presence of a superior option and many fewer desirable options will result in a more satisfying decision. Third, there is a negative relationship between choice assortment or quantity and satisfaction only in people less familiar with the choice set. This means that if the person making a choice has expertise in the subject matter, they can more easily sort through the options and not be overwhelmed by the variety.

In his book “The Paradox of Choice,” Schwartz outlines the steps of decision making which start from figuring out goals to evaluating the importance of each goal and moves on to arraying the options according to how well they meet each goal and then evaluating how likely each of the options is to meet the goals and finally to picking the winning option. The problem is, the more options one has, the harder it is to make a comparison across products. If one has to compare an item across 50 dimensions instead of 3, there’s a risk they’re missing out on “the one.” That’s the paradox — having a variety of options is good, it drives customer consideration. But once the number of choices gets too high, a person’s happiness goes down.

Choice overload is reversed when people choose for another person. It was found that overload is context-dependent: choosing from many alternatives by itself is not demotivating, it is not always a case of whether choices differ for the self and others at risk, but rather according to a selective focus on positive and negative information. Evidence shows there is a different regulatory focus for others compared to the self in decision-making. Therefore, there may be substantial implications for a variety of psychological processes about self-other decision-making. Among personal decision-makers, a prevention focus is activated and people are more satisfied with their choices after choosing among a few options compared to many options, i.e. choice overload. However, individuals experience a reverse choice overload effect when acting as proxy decision-makers.

The psychological phenomenon of overchoice can most often be seen in economic applications. Having more choices, such as a vast amount of goods and services available, appears to be appealing initially, but too many choices can make decisions more difficult. A consumer can only process seven items at a time, after that the consumer would have to create a coping strategy to make an informed decision. This can lead to consumers being indecisive, unhappy, and even refraining from making the choice or purchase at all. Alvin Toffler noted that as the choice turns to overchoice, “freedom of more choices” becomes the opposite — the “unfreedom”. Often, a customer decides without sufficiently researching his choices, which may often require days. When confronted with too many choices especially under a time constraint, many people prefer to make no choice at all, even if making a choice would lead to a better outcome.

Too much choice is the cause of mental anguish for some people. Economist Herman Simon theorised those decision-making styles fall into two types. The Satisficers are people who would rather make an “ok decision” than the perfect decision. They’ve spent some time considering their options, but haven’t belaboured the process. They tend to be more satisfied with their choice because they don’t consider all the available information. Satisficers settle for an option that’s “good enough” and move on. Satisficers decide once their criteria are met; when they find the hotel or the pasta sauce that has the qualities they want, they’re satisfied. The Maximizers on the other hand are those who want to make the best possible decision. They can’t choose until they’ve deeply examined every possible option. Research from Swarthmore College found that Maximizers reported significantly less life satisfaction, happiness, optimism, and self-esteem. They also experienced much higher levels of and regret and depression than Satisficers. The more options people have, the more likely they are to be disappointed in their choice. You never feel that you made the best decision because there were too many options to consider.

There are two steps involved in choosing to purchase. First, the consumer selects an assortment. Second, the consumer chooses an option within the assortment. Variety and complexity vary in their importance in carrying out these steps successfully, resulting in the consumer deciding to make a purchase. Variety is the positive aspect of assortment. When selecting an assortment during the perception stage, the first stage of deciding, consumers want more variety. Complexity is the negative aspect of assortment. Complexity is important for the second step in making a choice—when a consumer needs to choose an option from an assortment. When choosing an individual item within an assortment, too much variety increases complexity. This can cause a consumer to delay or opt-out of making a decision.

Images are processed as a whole when making a purchasing decision. This means they require less mental effort to be processed which gives the consumer a sense that the information is being processed faster. Consumers prefer this visual shortcut to process, termed “visual heuristic”, no matter how big the choice set size. Images increase our perceived variety of options. Variety is good when making the first step of choosing an assortment. On the other hand, verbal descriptions are processed in a way that the words that make up a sentence are perceived individually. That is, our minds string words along to develop our understanding. In larger choice sets where there is more variety, perceived complexity decreases when verbal descriptions are used.

Retailers and manufacturers can combat Choice Overload by offering fewer options which may seem counterintuitive in today’s age of personalization with more options needed to be limited to maximize sales. For example, Procter & Gamble found that a decrease in the number of Head & Shoulders varieties resulted in a 10% increase in revenue. They need to make it easy to compare features across products so it becomes easy for customers to choose between non-equal options and frame the use of each.

The choice is a good thing, but when we are faced with too many of them, we get into a sort of analysis paralysis which makes choosing something extremely difficult and we soon start to second guess our choices. When the number of options available is limited, it does take away that complexity we have in making choices, but with the reduction in choices, as consumers, it makes it easy to make a decision and, in the end, it’s this reduction in complexity that will smooth the way.