During one of the International Women’s Day events in February, I heard something that made me want to check it out further. According to an analysis by Oxfam, if women around the world received the minimum wage for every hour of their unpaid labour, they would have contributed a staggering $10.9 trillion to the global economy in 2020 – more than twice the size of the global tech industry that same year, valued at $5.2 trillion. Women’s unpaid labour is a staggering economic contribution that often goes unrecognised and undervalued.

Unpaid labour falls into two main categories: unpaid work within the production boundary of the System of National Accounts (SNA), such as subsistence agriculture or construction of one’s own home, which contributes to GDP but is not monetarily compensated; and unpaid work outside the SNA production boundary, such as domestic labour like cooking, cleaning, childcare, and caring for the elderly or sick within households for their own consumption. This type of unpaid labor is not included in GDP calculations.

The key aspects that define unpaid labor are that it involves mental or physical effort and is costly in terms of time and resources; the individual performing the activity is not remunerated or paid for their work; and it includes activities necessary for the health, well-being, maintenance, and protection of household members or the household itself.

Unpaid labour encompasses a wide range of activities beyond just household chores, such as volunteering, interning, and other forms of unpaid community work. However, the term “unpaid care work” specifically refers to unpaid domestic activities like cooking, cleaning, childcare, and caring for other dependents within the household.

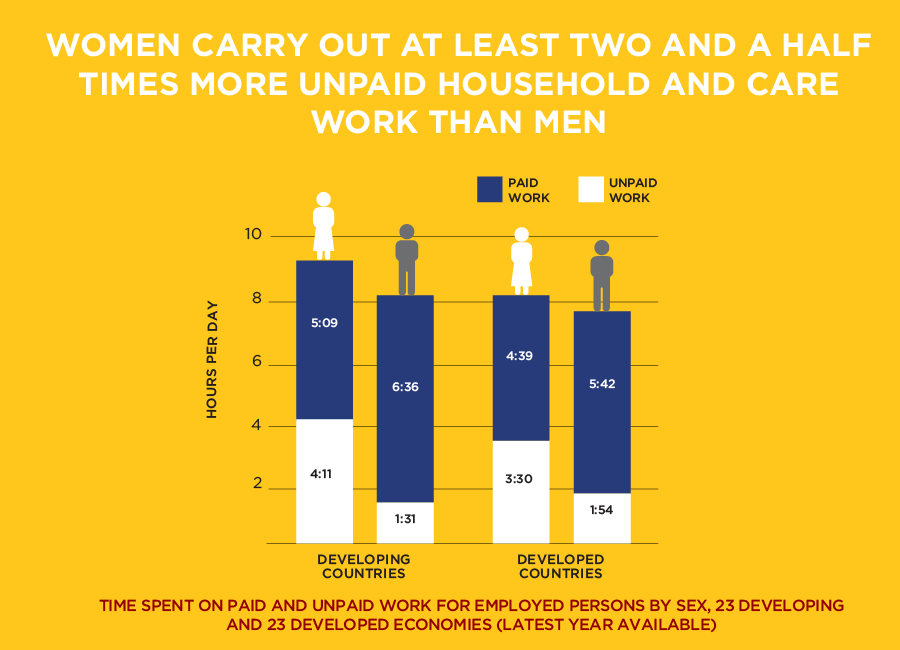

Women bear a disproportionate share of this invisible burden. Oxfam reports that women and girls handle more than three-quarters or 75%, of the world’s unpaid care work, carrying out 12.5 billion hours of this work every day. In the United States, women complete an average of 4.5 hours of unpaid labour daily, while men complete 2.8 hours.

The unequal distribution of unpaid care work between women and men represents a violation of women’s rights and a barrier to their economic empowerment. This gender gap persists across regions, socio-economic classes, and cultures, rooted in discriminatory social norms and stereotypes about gender roles.

In some countries, the gap is particularly stark. In India, women spend almost six hours a day managing the home, while Indian men spend a paltry 52 minutes. Even in more gender-equal countries like Sweden and Norway, women still complete 42 and 50 more minutes of unpaid labour per day, respectively, than men.

The disproportionate share of unpaid work that women do has a significant impact on their careers and professional opportunities. Women’s career paths are often hampered by a “broken rung,” facing difficulties when it comes to stepping up to managerial roles. For every 100 men promoted from entry-level to manager, only 87 women were promoted, according to 2023 data.

Unpaid care work is also directly linked to the gender pay gap within households. Because women’s salaries tend to be lower, they are usually the ones who stop working to take over childcare, further exacerbating the pay gap. Additionally, women responsible for a large amount of unpaid care work may find it difficult to work full-time hours, limiting their job opportunities.

Tackling entrenched social norms and gender stereotypes is a crucial step in redistributing responsibilities for care and housework between women and men. Public awareness campaigns, education programmes, and financial incentives for fathers to take parental leave could promote a fairer distribution of the unpaid workload.

Countries with robust welfare programs that provide care for children and older people, such as Sweden, Denmark, and Norway, have higher gender parity in unpaid labour. Sweden, for example, gives parents 480 days of paid parental leave to be shared between them, promoting a more equal sharing of care responsibilities. Creating a supportive culture for working parents and caregivers through policies like flexible work schedules and teleworking, can also help women balance their paid and unpaid responsibilities.

Governments can also recognise and measure unpaid labour and incorporate the measurement of unpaid care work into national statistics and GDP calculations to make the economic value of this work visible. They should also conduct research and collect data on the time spent on unpaid care work by women and men to better understand the issue. Governments should also invest in public services and infrastructure that can reduce the time and effort required for unpaid care tasks, such as childcare facilities, elder care services, and time-saving household technologies, as well as implement family-friendly policies like flexible work arrangements, teleworking, and paid parental leave to enable both women and men to better balance paid work and unpaid care responsibilities. This will reduce the burden of unpaid labour.

They can also redistribute unpaid labour more equally by tackling discriminatory social norms and gender stereotypes that associate unpaid care work with women, through public awareness campaigns and education programs, providing financial incentives and policies to encourage men to take on a greater share of unpaid care work, such as “use-it-or-lose-it” parental leave policies, and adopting a “care lens” in policymaking across different sectors to ensure that the redistribution of unpaid care work is considered. Legal and social protections for paid care workers, like improving wages, working conditions, and social protections for paid domestic and care workers, who are often women and work in the informal sector, should be initiated to achieve greater gender equality and unlock the full economic potential of women.

The staggering value of women’s unpaid labour, estimated at $10.9 trillion globally, highlights the urgent need to recognise, reduce, and redistribute this invisible burden. Addressing gender inequality in unpaid care work is not only a matter of women’s rights and economic empowerment but also a crucial step towards achieving gender equality and unlocking the full potential of societies worldwide. As we confront the realities of women’s unpaid labour and its profound economic and social implications, we are reminded of the urgent need for collective action and solidarity. By recognising the true value of women’s contributions, advocating for policy reforms, and challenging gender norms and stereotypes, we can create a more just, equitable, and inclusive world for all. Let us harness the power of awareness, advocacy, and activism to dismantle the invisible barriers that perpetuate gender inequality and pave the way for a brighter future for generations to come.