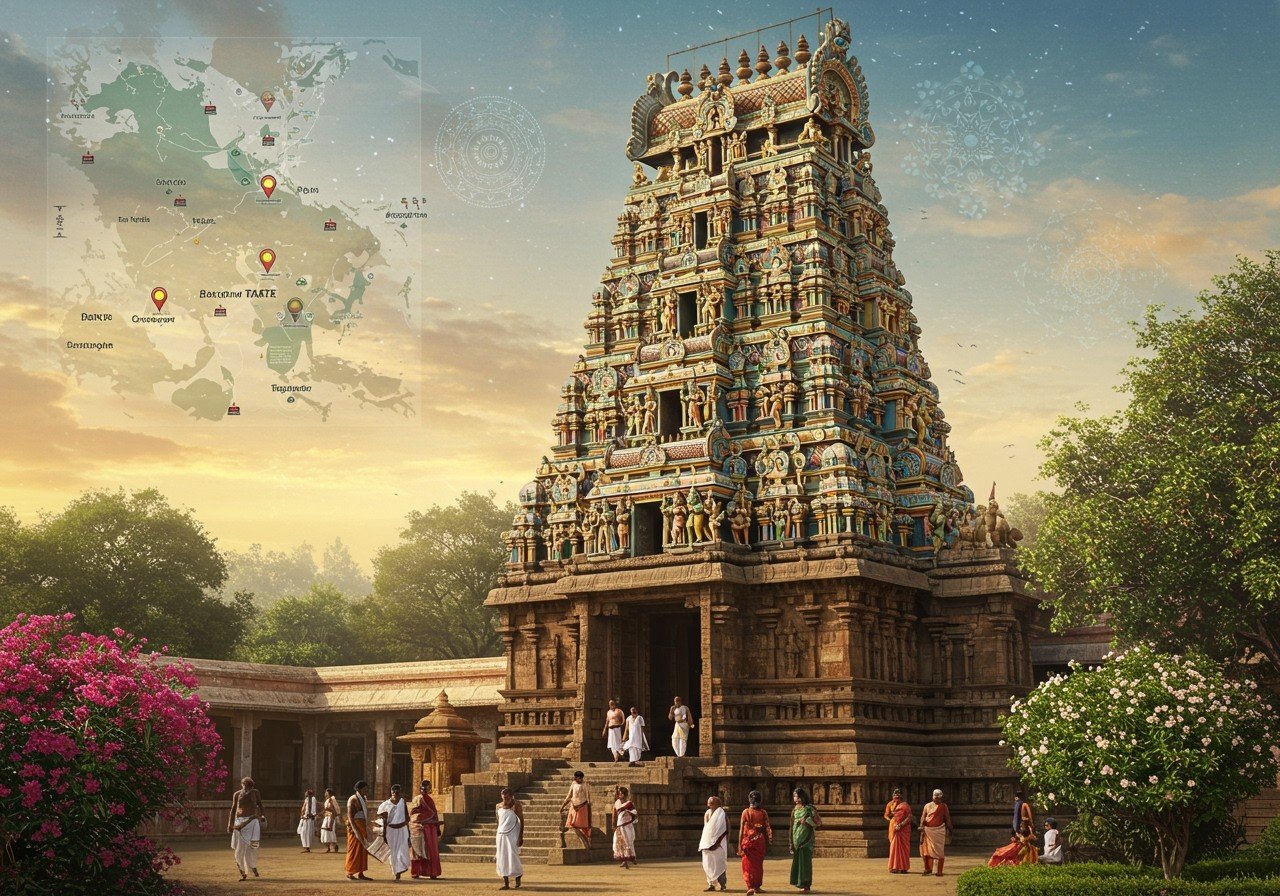

Situated atop the sacred Shri Shaila Mountain in the Nallamala Hills of Andhra Pradesh, the Mallikarjuna Temple in Srisailam is one of the twelve revered Jyotirlinga temples of Lord Shiva. Unique among the Jyotirlingas, Mallikarjuna also simultaneously enshrines a Shakti Peetha, making it a rare and deeply sacred space for the worship of Shiva and his consort Parvati, worshipped here as Bhramaramba. This convergence of Shaivism and Shaktism symbolises cosmic balance and union, earning the temple the epithet Kailash of the South. For centuries, pilgrims have journeyed through dense forests and rugged hills to seek blessings from the divine pair, believing the temple to be a source of spiritual power, peace, and transformation.

The Mallikarjuna Temple brims with ancient mythic tales that illuminate its divine origins and cosmic significance. According to one legend found in the Agni Purana and Skanda Purana, a pivotal event shaped the temple’s sanctity: the reconciliation and union of Lord Shiva and Goddess Parvati on the sacred hill of Shri Shaila.

One popular story recounts the marriage dilemma of Shiva’s sons, Ganesha and Kartikeya. When deciding which son should marry first, Shiva proposed a cosmic contest: whoever circled the universe first would win. Kartikeya rode off on his peacock mount to physically circle the world, while Ganesha circled his parents, Shiva and Parvati, symbolising the universe itself. Ganesha’s cleverness won him the first marriage, making Kartikeya angry and withdrawing to isolation.

To bring Kartikeya back, Shiva and Parvati took residence on Sri Shaila Mountain in the forms of Mallikarjuna (Shiva) and Bhramaramba (Parvati), thereby turning the hill into a sacred abode. It is believed that on new moon nights or Amavasya, Shiva appears as Mallikarjuna, and on full moon nights or Poornima, Parvati appears as Mallika, and together they await their son’s return.

Another legend suggests that Mallikarjuna is one of the three divine Shiva lingas appearing during different yugas at Srisailam, Draksharamam, and Kaleshwaram, representing his omnipresence. The name Mallikarjuna itself is derived from Mallika, meaning jasmine, believed to be the flower with which Shiva’s linga was worshipped here.

Local tribal lore enriches the temple’s mystique as well. The Chenchu tribes, forest dwellers who historically live in the area, regard Shiva as a hunter who married a Chenchu maiden, symbolising a deep connection between nature, divinity, and humanity.

Mallikarjuna Temple stands as one of Andhra Pradesh’s oldest and most venerated religious sites, dating back over a millennium. Archaeological and inscriptional evidence traces the temple’s roots to the Satavahana dynasty (circa 2nd century CE), with subsequent expansions by dynasties including the Chalukyas, Pallavas, and Reddys. The Satavahanas left inscriptions acknowledging the temple and its hill, sanctifying it as a place of divine worship. Brief mentions appear in ancient texts, underscoring its status as a spiritual hub.

Over centuries, rulers like Prolay Verma and Anavema Reddy developed roads and mandapas or pillared halls facilitating pilgrim access into the rugged hills. The temple prospered through the classical and medieval eras, with notable contributions from the Vijayanagara Empire, which enhanced the temple complex, incorporating elaborate mandapas and gopurams or gateway towers that showcase their architectural patronage.

The temple is also historically critical because it is one of the only places in India where both a Jyotirlinga Shiva linga and a Shakti Peetha exist under one roof. As per mythology, this spot is where a part of Goddess Sati’s body (her upper lip or mukh) fell during Shiva’s cosmic dance of grief.

Philosophers and saints such as Adi Shankaracharya, Siddha Nagarjuna, and Allama Prabhu paid homage to Mallikarjuna, contributing to its stature as a center for Shaiva-Shakta theological discourse.

Mallikarjuna Temple is an architectural marvel distinguished by the Dravidian style prevalent in South India, enhanced by the influence of the Chalukyas and Vijayanagara artisans. Set on a sprawling temple complex amidst the dense Nallamala forests, the structure features multiple gopurams or towering gateways with each gate, intricately carved with mythological scenes and divine figures, that serve as a majestic entrance, symbolising the transition from the mundane to the sacred. There are also lavishly decorated Mandapas and Sabhas or halls to host religious gatherings and rituals. The Grabhagriha or Sanctum houses the Mallikarjuna Jyotirlinga for Shiva and the Bhramaramba Shakti Peetha for Parvati; both are freestanding and receive individual worship. The enduring granite walls blend with the natural terrain, evoking a sense of the divine emerging from the earth itself while intricate sculptures and motifs including wall carvings narrate Shiva’s legends, goddess lore, and depictions of flora and fauna native to the region, reflecting local aesthetics. The temple complex includes a thousand lingas or Sahasra Lingas, commissioned by Lord Rama and the Pandavas, further enriching the sacred environment. The temple’s architectural design cleverly integrates with its hilly setting, with steps and courtyards guiding pilgrims upward toward the sanctum, symbolising the spiritual ascent.

Mallikarjuna Temple is alive with daily rituals and vibrant festivals that celebrate Shiva and Shakti’s cosmic dance. Daily pujas begin early morning with abhisheka, bathing the lingam with holy water, milk, honey, and other sacred substances, accompanied by Vedic chants. Devotional singing and lamp waving rituals take place at multiple times, creating an immersive sensory worship experience.

Mahashivaratri is the most important festival, characterised by all-night vigils, fasts, and spiritual discourses. The temple also celebrates Navaratri, celebrating the goddess’s power, attracting thousands from across India. Devotees participate in the ritualistic circumambulation of the temple and the Sahasra Linga complex. Local traditions by the Chenchu tribes include offerings and ecological respect rituals, highlighting nature’s role in the temple’s sanctity. The temple management facilitates feeding and accommodation for pilgrims, supported by local societies that organize cultural programs and care for the shrine.

The journey to Mallikarjuna Temple is both a physical and spiritual pilgrimage through a lush, forested landscape teeming with biodiversity. Srisailam is connected by road and rail, with nearest major airports at Hyderabad and Kurnool. The last leg involves ascending rugged hill paths amid picturesque landscapes. The temple’s location in dense forests and hills adds a sense of seclusion and sanctity. Pilgrims often recount sensations of peace and divine presence amid chants, ringing bells, and the natural sounds of wildlife. Numerous dharamshalas or pilgrim hostels, eateries, and markets provide support to visitors, blending tradition with modern needs. Many pilgrims share stories of miraculous healing and spiritual experiences, attributing them to the temple’s cosmic energies and the mountain’s sanctity.

The Mallikarjuna Temple influences literature, music, and art, particularly in the Andhra region. The temple and its legends feature in classical Telugu and Sanskrit poetry, as well as oral folklore, which celebrates the divine union of Lord Shiva and Goddess Parvati. Devotional songs, especially during festivals, draw from regional and classical traditions, creating a rich sonic tapestry that resonates with the natural environment. The temple’s carvings influence contemporary art forms as well, inspiring devotees and artists alike. Beyond faith, the temple is a source of cultural pride for communities around Srisailam, integrating tribal heritage and mainstream Hindu traditions. The bees said to have made the temple their home, without harming worshippers, and stories of divine protection deepen the temple’s mythos within local culture.

Today, Mallikarjuna Temple serves as both a major pilgrimage destination and a cultural heritage site. The Sri Bhramaramba Mallikarjuna Devasthanam oversees temple operations, pilgrimage infrastructure, and festivals. Significant investments in roads, accommodations, and amenities have facilitated growing visitor numbers while preserving spiritual rhythms. Mahashivaratri attracts a national and international audience, blending traditional rituals with modern event management. Ongoing restoration projects safeguard ancient structures while adapting to environmental and tourist pressures. The temple attracts devotees from diverse backgrounds, including urban and rural, domestic and overseas, reflecting its broad spiritual appeal.

The Mallikarjuna Temple at Srisailam stands as a celestial beacon embodying the cosmic harmony of Shiva and Shakti—the masculine and feminine divine principles. Its ancient legends, rich history, and mesmerising architecture invite pilgrims to a spiritual journey of devotion and discovery. Uniting primal forest landscapes with sacred stone, it affirms India’s layered cultural and religious heritage. As a vital node in the Jyotirlinga circuit and a symbol of balance between power and grace, Mallikarjuna Temple continues to inspire faith, scholarship, and awe across generations.