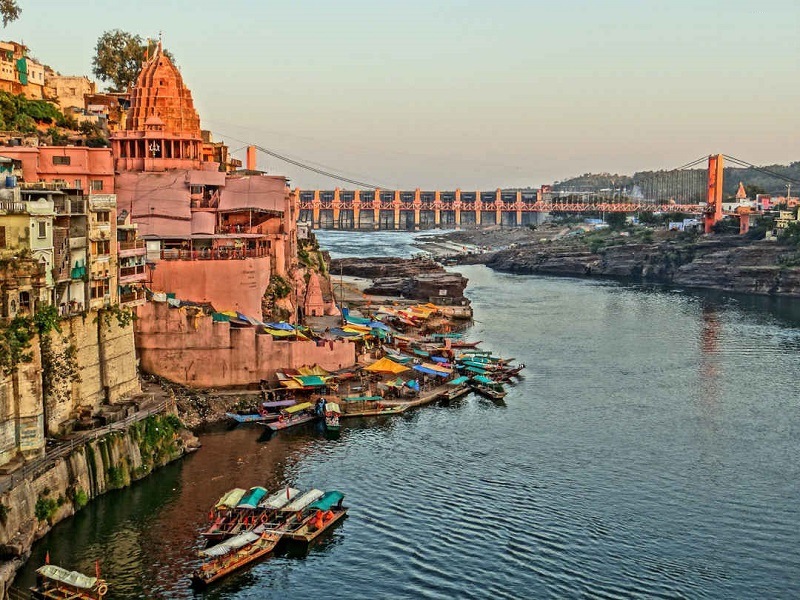

The Omkareshwar Temple is one of India’s twelve revered Jyotirlinga temples dedicated to Lord Shiva, standing majestically on Mandhata Island amid the tranquil and sacred flow of the Narmada River in Khandwa district, Madhya Pradesh. The island itself is said to be naturally shaped like the sacred syllable Om, a symbol of the cosmic sound and creation in Hindu tradition. Both the region’s geography and mythology infuse this site with deep spiritual resonance, making it a crucial place of pilgrimage for seekers, saints, and historians alike. Omkareshwar’s importance stretches far beyond religious devotion; it is a site of harmony where legend, landscape, and architecture unite in eternal homage to Lord Shiva.

The legends that suffuse Omkareshwar Temple are as vibrant and multi-layered as the Narmada’s current, each weaving together divine drama, cosmic symbolism, and human aspiration. The most prominent legend tells of Vindhya, the mountain deity who, overflowing with pride, desired to surpass Mount Meru. The sage Narada detected this pride and advised Vindhya to pray for liberation from his arrogance and its attendant sins. Vindhya’s intense penance to Shiva led to the creation of a sacred geometrical diagram and a linga fashioned from sand and clay. Pleased by Vindhya’s devotion, Shiva manifested in two forms: Omkareshwar and Amaleshwar. The island gained recognition as Omkareshwar because the mud mound appeared in the form of “Om”.

Another legend centers around King Mandhata, a devout ruler from the Ikshvaku dynasty, ancestors of Lord Rama, who performed intense penance atop Mandhata Parvat. His unwavering devotion attracted the grace of Lord Shiva, who incarnated as the Jyotirlinga at Omkareshwar, blessing the land and its people. Mandhata’s sons, Ambarish and Muchukunda, undertook their own spiritual practices here, further amplifying the site’s sacred aura.

Hindu scriptures also recount an epic cosmic battle in which the Devas or gods were defeated by the Danavas or demons. Bereft and seeking salvation, the Devas performed severe austerities, praying to Shiva at Omkareshwar. Pleased by their prayers, Shiva manifested as the Jyotirlinga, in Omkareshwar, vanquished the demons, and restored balance to the cosmos, reaffirming Omkareshwar’s position as a place of divine intervention and protection.

Omkareshwar is deeply tied to the Advaita Vedanta philosophy and the eternal mantra “Om.” It symbolises non-duality, the unity of creation and creator, and the boundless resonance of the cosmic sound. Tradition holds that Adi Shankaracharya met his guru, Govinda Bhagavatpada, in a cave near the temple, a pivotal moment in Indian philosophical history that continues to impact spiritual seekers worldwide.

The spiritual and historical canvas of Omkareshwar Temple is rich, stretching over hundreds of generations. Historical accounts suggest that the original temple was commissioned by the Paramara Kings of Malwa in the 11th century CE. Over the centuries, it faced destruction and restoration, changing hands between rulers and dynasties. The Chauhan Kings administered the temple in later centuries. During the 13th century, Muslim invasions, starting with Mahmud Ghazni, led to periods of destruction and looting, but local rulers and devotees ensured restoration and continued worship. In the 18th century, Queen Ahilyabai Holkar, a renowned patron of Hindu temples, undertook extensive reconstruction and added significant architectural embellishments.

The temple and Mandhata Island feature prominently in the Skanda Purana, Shiva Purana, and other ancient scriptures, which extol the spiritual power of its location. The sacred geography is highlighted as a tirtha, or crossing place where heaven and earth meet, amplified by the confluence of the Narmada and Kaveri rivers.

The island’s natural shape, resembling the word “Om,” sets Omkareshwar apart from all other Jyotirlinga sites, while the surrounding ghats, forests, and riverbanks combine wild beauty with meditative calm. Adi Shankaracharya’s visit and extended meditation here serve as a bridge connecting Omkareshwar to the broader philosophical, sannyasa, and devotional traditions throughout India.

Omkareshwar Temple is as much a marvel of ancient architecture as it is a centre of spiritual energy. The temple is built in classic Nagara style with intricately carved spires and shikharas, merging gracefully with the island’s contours and riverbanks. The sanctum sanctorum or garbhagriha houses the revered lingam. The temple’s structure is predominantly stone, shaped to withstand centuries of monsoon and river flooding, reflecting both resilience and architectural innovation. Mandapas or pillared halls, circumambulatory paths, and subsidiary shrines dedicated to Goddess Parvati and Lord Ganesh enhance the spiritual and functional aspects of the site. Elaborate carvings on pillars, ceilings, and external walls depict scenes from Shiva’s lore, nature motifs, and floral designs emblematic of the Malwa region. The temple’s ornamentation honors both royal patrons and local artistic traditions, contributing to Omkareshwar’s vibrant visual identity.

The Mamleshwar Temple, located on the opposite bank, considered by some traditions as equally sacred. Adi Shankara’s Cave is where Adi Shankaracharya met his guru, is marked by an image and often visited by spiritual aspirants. Archaeological remains of Jain and Hindu temples, known as the 24 Avatars Group, showcase the island’s multi-faith heritage.

The spiritual life at Omkareshwar pulses with daily rituals and annual festivals that unite devotees in worship and celebration. Daily pujas include the abhisheka when the linga is bathed with water from the Narmada, milk, honey, and fragrant flowers, accompanied by the rhythmic chanting of mantras. Multiple times each day, ceremonial lamps, music, and prayers unfold, invoking the blessings of Omkareshwar. Devotees present coconuts, incense, silk, and garlands, often completing a circumambulation of the temple and island, a rite said to bestow merit and purification.

Mahashivaratri is the most important festival, marked by vigil, fasting, grand processions, and elaborate worship attended by tens of thousands of pilgrims. The fifth lunar month, Shravan, is filled with special pujas, communal singing, and heightened devotion. Local customs reflect both Malwa and broader Indian traditions, with community involvement spanning from offering food to maintaining cleanliness and hosting guests.

A pilgrimage to Omkareshwar is as much a journey of spirit as one of landscape. Omkareshwar is connected by road and rail from Indore, Khandwa, and Ujjain. The nearest airport is Indore, about 80 km away. After arriving in the bustling town, pilgrims cross the Narmada by ferry or foot bridges to reach Mandhata Island, with its serene ghats, steps, and forested terrain. Eateries, dharamshalas (pilgrim hostels), lodges, and ashrams cater to all travelers, offering simple vegetarian fare and local delicacies. The town radiates a welcoming spirit with locals, priests, and volunteers supporting visitors in their search for spiritual solace and ritual guidance.

The sounds of water, bells, and chanting intermingle, creating a meditative ambiance that resonates with ancient stones and smiling faces. Many share tales of healing, inner peace, inspiration, and unexpected blessings, the island’s energy and landscape accentuate the sense of divine presence.

Omkareshwar’s reach goes far beyond its physical boundaries, shaping literature, music, art, and local identity. The temple is extolled in classical Sanskrit and vernacular poetry; devotional songs and stories celebrate Shiva’s victories, Mandhata’s penance, and the island’s mystical power. Regional and national artists compose bhajans and ragas inspired by the temple and the chanting reverberating across the river. Stone sculptors and local artisans produce icons, carvings, and paintings reflecting the temple’s motifs. Fairs and festivals feature dance, drama, and crafts, sustaining Omkareshwar as a vibrant cultural hub in the region. Omkareshwar shapes community pride for residents and the Malwa region, fostering a sense of belonging. Spiritual anecdotes and legends are shared with every visitor, passed down through generations and etched into local folklore.

Today, Omkareshwar Temple is a dynamic pilgrimage and tourist destination, managing ancient traditions amid contemporary needs. The temple is administered by local trusts and authorities, maintaining daily rituals, festival calendars, and infrastructural upgrades. Digital registration, security enhancements, guided tours, and heritage conservation reflect ongoing adaptation.

Visitor numbers swell during Mahashivaratri, the Shravan month, and holidays, with improved travel facilities and hospitality. Environmental stewardship ensures preservation of the river, forests, and historical monuments. Major conservation efforts include repairs after monsoon damage, safeguarding sculpture, and archaeological work. Pilgrims and tourists hail from across India and the globe, reflecting the temple’s universal spiritual magnetism.

The Omkareshwar Temple, held tenderly in the embrace of the Narmada’s waters and the shape of Om, stands as a testament to the unity of creation and consciousness embodied in Lord Shiva. Its tapestry of legend, sanctity, history, and landscape offers a sanctuary for reflection, transformation, and transcendence. In the grand circuit of Jyotirlinga temples, Omkareshwar is both a spiritual and philosophical anchor, inviting every seeker to listen to the eternal sound within and without, in every stone, wave, and breath.