The Ranakpur Jawai Bandh Festival is a vibrant celebration that showcases the rich cultural heritage, natural beauty, and artistic traditions of Rajasthan. Held annually in the Pali district of Rajasthan, this two-day festival has become a significant event on the state’s cultural calendar, attracting visitors from across India and beyond. The festival takes place in the picturesque settings of Ranakpur, known for its stunning Jain temples, and the Jawai region, famous for its unique landscape and wildlife. Organised by the Department of Tourism, Government of Rajasthan, the Ranakpur Jawai Bandh Festival aims to provide visitors with an immersive experience of Rajasthan’s diverse cultural tapestry.

The Ranakpur Jawai Bandh Festival is a relatively new addition to Rajasthan’s festival calendar, having been initiated by the state government as part of its efforts to promote cultural tourism and showcase lesser-known regions of Rajasthan. While the festival itself doesn’t have ancient roots, it draws upon centuries-old traditions, art forms, and natural heritage of the region.

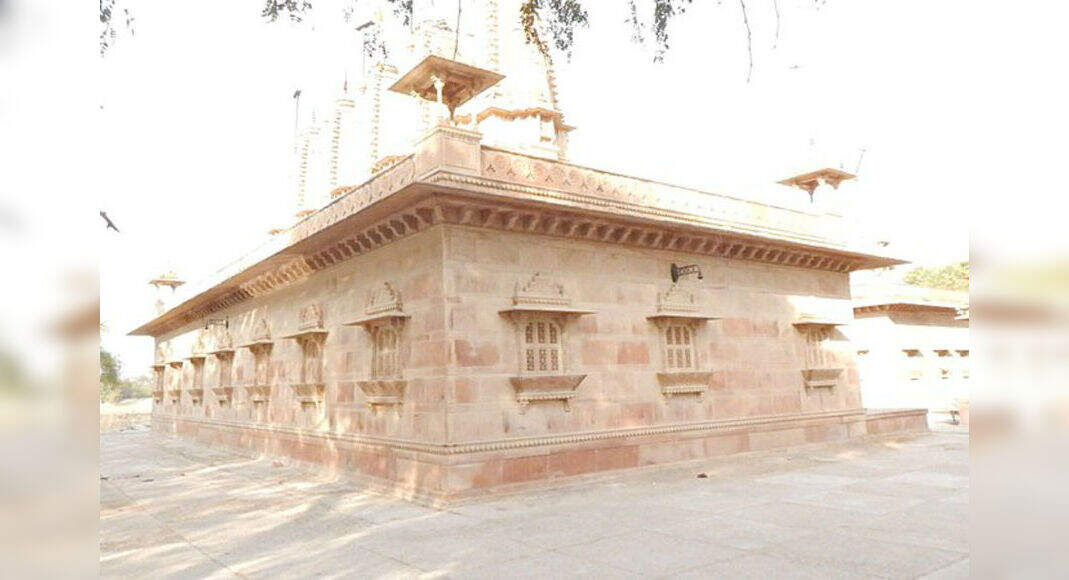

The idea behind the festival was to create a platform that could highlight the unique offerings of the Ranakpur and Jawai areas. Ranakpur, with its magnificent 15th-century Jain temples, represents the architectural and spiritual heritage of Rajasthan. On the other hand, the Jawai region, with its distinctive rocky landscape and thriving leopard population, showcases the state’s natural beauty and wildlife conservation efforts.

The festival was conceptualised to bridge these two aspects – the cultural and the natural – providing visitors with a holistic experience of Rajasthan. By doing so, it aims to promote sustainable tourism in the region, benefiting local communities while preserving the area’s cultural and natural heritage. Since its inception, the festival has grown in scale and popularity. What started as a local event has now become a much-anticipated annual celebration, drawing visitors from various parts of India and abroad. The festival’s program has expanded over the years, incorporating more activities and performances to cater to a diverse audience.

The Ranakpur Jawai Bandh Festival typically takes place in December, marking the onset of the winter tourist season in Rajasthan. The cool, pleasant weather of December provides an ideal backdrop for the outdoor activities and performances that form a significant part of the festival.

The festival is spread across two locations:

Ranakpur: Located in the Pali district of Rajasthan, Ranakpur is renowned for its stunning Jain temples. The main temple, dedicated to Adinath, is a marvel of architecture with its 1444 intricately carved marble pillars. The serene surroundings of Ranakpur, nestled in the Aravalli range, provide a perfect setting for the cultural and spiritual aspects of the festival.

Jawai: The Jawai region, named after the Jawai River and the Jawai Bandh or dam, is known for its unique landscape characterized by granite rock formations. This area is famous for its thriving leopard population and offers a stark yet beautiful contrast to the architectural splendor of Ranakpur.

The dual location of the festival allows visitors to experience two distinct facets of Rajasthan – its rich cultural heritage and its raw natural beauty – within a single event.

The Ranakpur Jawai Bandh Festival offers a diverse range of activities that cater to various interests. The festival begins each day with early morning yoga and meditation sessions. These sessions are typically held in the serene surroundings of Ranakpur, with the majestic Jain temples providing a stunning backdrop. Experienced yoga instructors guide participants through various asanas and meditation techniques, allowing visitors to start their day in a peaceful and rejuvenating manner. Guided nature walks are organized in both Ranakpur and Jawai. In Ranakpur, these walks often focus on the local flora and fauna found in the Aravalli range. In Jawai, the nature walks offer an opportunity to explore the unique rocky landscape and learn about the region’s ecology. One of the most exciting activities of the festival is the jeep safari in the Jawai region. These safaris offer visitors a chance to explore the rugged terrain and potentially spot the elusive leopards that the area is famous for. The safaris are led by experienced local guides who share their knowledge about the region’s wildlife and conservation efforts. As evening falls, the festival area is illuminated with thousands of earthen lamps or diyas, creating a magical atmosphere. This Deepotsav or a festival of lights is a visual spectacle that adds a touch of spiritual beauty to the festivities.

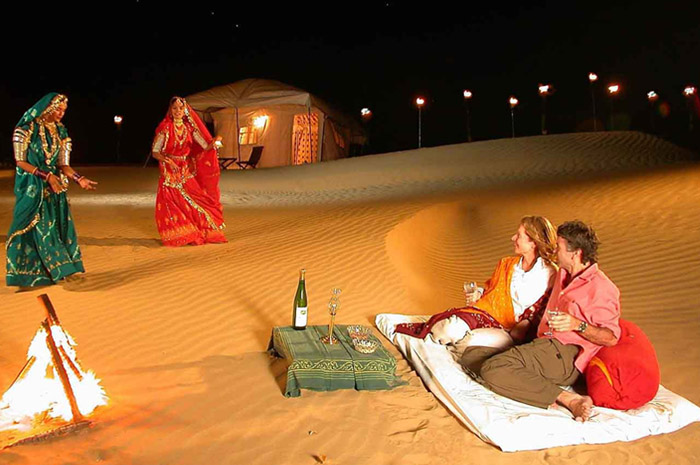

The evenings are dedicated to cultural performances that showcase the rich artistic heritage of Rajasthan. These performances include traditional Rajasthani folk music, including genres like Manganiyar and Langa, that fill the air with soulful melodies, energetic performances of Rajasthani folk dances such as Ghoomar, Kalbelia, and Bhavai that enthral the audience, and traditional Rajasthani puppet shows, known as Kathputli, that narrate folk tales and legends.

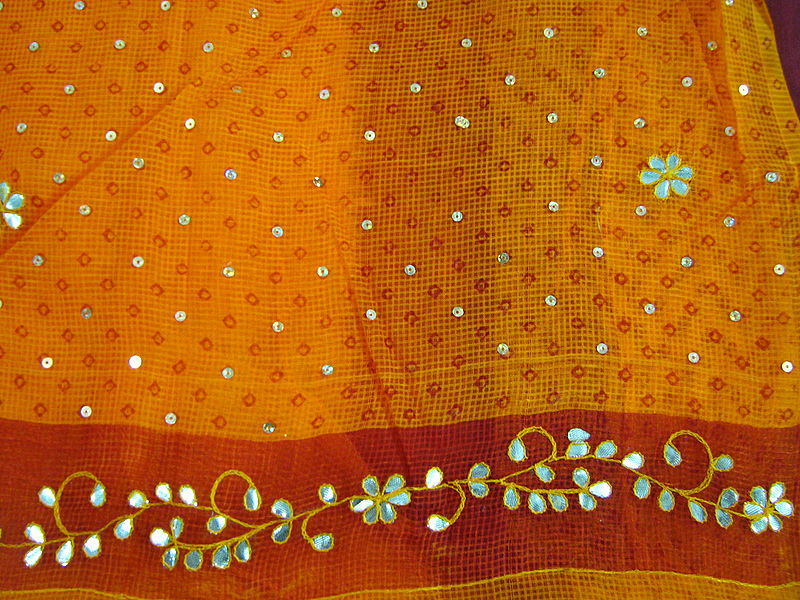

Local artisans demonstrate their skills in various traditional Rajasthani crafts such as block printing, tie-and-dye, pottery, and miniature painting. Visitors can watch the artisans at work and even try their hand at some of these crafts. Given the picturesque locations of Ranakpur and Jawai, the festival organises photography tours. These tours are led by professional photographers who guide participants on capturing the best shots of the temples, landscapes, and wildlife. Food stalls offering a variety of Rajasthani delicacies are set up during the festival. Visitors can savour authentic dishes like Dal Baati Churma, Gatte ki Sabzi, and Ker Sangri, getting a taste of traditional Rajasthani hospitality. For the more adventurous visitors, activities like rock climbing and rappelling are organized in the Jawai region, taking advantage of the area’s unique geological features. The clear night skies of the Jawai r. egion offer excellent conditions for stargazing. Astronomy enthusiasts guide visitors through constellations and share stories related to celestial bodies.

While the Ranakpur Jawai Bandh Festival is a relatively new event, it draws upon and celebrates cultural elements that have deep roots in Rajasthani tradition. The festival serves as a platform to showcase and preserve various aspects of Rajasthan’s rich cultural heritage. The stunning Jain temples of Ranakpur, which form a backdrop to many festival activities, are a testament to the architectural prowess of ancient India. Built in the 15th century, these temples, with their intricate marble carvings, represent the pinnacle of Maru-Gurjara architecture. The festival draws attention to this architectural marvel, promoting awareness and appreciation of India’s architectural heritage. The cultural performances during the festival play a crucial role in preserving and promoting Rajasthan’s folk arts. Many of these art forms, passed down through generations, face the risk of being lost in the face of modernization. By providing a platform for folk musicians, dancers, and puppeteers, the festival contributes to keeping these traditions alive.

The art and craft demonstrations during the festival showcase the skills of local artisans. Crafts like block printing, tie-and-dye, and miniature painting are integral to Rajasthan’s cultural identity. The festival not only provides exposure to these artisans but also helps in passing these skills to younger generations. The focus on traditional Rajasthani cuisine during the festival helps in preserving and promoting the state’s rich culinary heritage. Many of the dishes served at the festival have been part of Rajasthani cuisine for centuries, each with its own cultural significance and stories.

The festival, with its focus on both cultural heritage and natural beauty, emphasizes the traditional Rajasthani ethos of living in harmony with nature. This is particularly evident in the Jawai region, where local communities have coexisted with leopards for generations. The yoga and meditation sessions, as well as the Deepotsav, reflect the spiritual traditions that have long been a part of Rajasthani culture. These elements of the festival provide visitors with a glimpse into the spiritual practices that have shaped the region’s cultural landscape.

According to local legend, the construction of the main Ranakpur temple was inspired by a divine vision. It is said that a Jain businessman named Dharna Shah had a dream in which he saw a celestial vehicle. Following this vision, he commissioned the construction of the temple. The intricate design of the temple, with its numerous halls and 1444 pillars, is said to have been inspired by this divine vision.

The Jawai region is known for its unique coexistence between humans and leopards. Local folklore is rich with stories of the leopards being protectors of the land. Many villagers consider the leopards as guardians and believe that sighting a leopard is auspicious. These beliefs have contributed to the conservation efforts in the region.

Local legends speak of the construction of the Jawai Dam as a feat of human perseverance blessed by divine intervention. Stories tell of how the initial attempts to build the dam failed until local deities were propitiated, after which the construction was completed successfully.

The Aravalli range, which forms the backdrop of both Ranakpur and Jawai, features in many mythological tales. One legend states that the Aravalli range was formed when Lakshman, brother of Lord Rama, drew a line with an arrow to protect Sita during their exile.

Near the Ranakpur temples stands an ancient banyan tree that is the subject of many local legends. Some believe that the tree has healing properties, while others consider it a wishing tree. During the festival, many visitors pay their respects to this tree.

The Ranakpur Jawai Bandh Festival plays a significant role in promoting environmental awareness and conservation efforts in the region. The Jawai region is known for its successful conservation of leopards. The festival helps raise awareness about the importance of wildlife conservation and the unique ecosystem of the area. During the jeep safaris and nature walks, guides educate visitors about the local flora and fauna and the conservation efforts underway.

The festival promotes sustainable tourism practices. By showcasing the natural beauty of the region, it encourages a form of tourism that is respectful of the local environment and wildlife. The festival organisers emphasise responsible behavior during wildlife safaris and nature walks. The Jawai Dam, which gives the festival part of its name, is crucial for water management in the region. The festival draws attention to the importance of water conservation in this semi-arid region of Rajasthan. Through interactions with local communities, the festival helps highlight traditional ecological knowledge. This includes local practices of water harvesting, sustainable agriculture, and coexistence with wildlife. The festival has adopted a plastic-free policy, encouraging the use of eco-friendly materials. This initiative not only helps keep the festival area clean but also spreads awareness about reducing plastic usage.

The Ranakpur Jawai Bandh Festival has a significant positive economic impact on the local communities. The festival attracts tourists from various parts of India and abroad, providing a boost to the local tourism industry. Hotels, guesthouses, and homestays in the region see increased bookings during the festival period. The festival creates temporary employment opportunities for local residents. This includes jobs in event management, hospitality, transportation, and as guides for various activities. The art and craft demonstrations during the festival provide a platform for local artisans to showcase and sell their products. This direct interaction with customers often leads to increased sales and sometimes long-term business relationships. Local restaurants, shops, and service providers see increased business during the festival. The influx of visitors benefits various sectors of the local economy. By showcasing the attractions of Ranakpur and Jawai, the festival contributes to long-term tourism promotion for the region. Many first-time visitors during the festival often plan return trips, contributing to sustained tourism growth.

While the Ranakpur Jawai Bandh Festival has been successful in promoting the region’s cultural and natural heritage, it also faces certain challenges. One of the primary challenges is maintaining a balance between promoting tourism and ensuring the conservation of the region’s natural resources and wildlife. The increased footfall during the festival period needs to be managed carefully to minimize the impact on the local ecosystem. The growing popularity of the festival puts pressure on the local infrastructure. There’s a need for sustainable development of tourism infrastructure that can cater to the increased number of visitors without compromising the region’s natural beauty. As the festival grows, there’s a challenge in maintaining the authenticity of cultural presentations. There’s a need to ensure that commercialisation doesn’t lead to dilution of traditional art forms and practices. Ensuring meaningful involvement of local communities in the planning and execution of the festival is crucial for its long-term success and sustainability. While the festival provides a significant boost during its duration, there’s a need to leverage its popularity for year-round tourism development in the region.

Looking to the future, the Ranakpur Jawai Bandh Festival has significant potential for growth and evolution. There are discussions about extending the duration of the festival to allow for more activities and to spread the tourist influx over a longer period. Future editions of the festival could have an increased focus on eco-tourism, promoting responsible travel practices and environmental education. The festival could evolve to include cultural exchange programs, inviting artists and performers from other parts of India and abroad to participate. The use of technology, such as virtual reality experiences of wildlife safaris or temple architecture, could be incorporated to enhance the visitor experience. The festival could serve as a platform for launching and showcasing research and conservation initiatives related to the region’s wildlife and ecology.

The Ranakpur Jawai Bandh Festival stands as a vibrant celebration of Rajasthan’s rich cultural heritage and natural beauty. By bringing together the architectural splendor of Ranakpur’s temples and the raw, rugged beauty of the Jawai landscape, the festival offers visitors a unique and comprehensive experience of Rajasthan. More than just a tourist event, the festival plays a crucial role in preserving and promoting various aspects of Rajasthani culture – from its folk arts and traditional crafts to its culinary heritage and spiritual practices. It serves as a platform for local artists and artisans to showcase their skills and find new audiences. Economically, the Ranakpur Jawai Bandh Festival has become a significant event for the local communities, providing various opportunities for employment and business.