Also known as Maha Vishuba Sankranti, Pana Sankranti is a vibrant and culturally significant festival celebrated in Odisha. This auspicious occasion marks the traditional Odia New Year and heralds the arrival of spring, serving as a time for renewal, spiritual reflection, and communal joy. Falling on the first day of the Odia calendar month of Baisakha, typically around mid-April, Pana Sankranti coincides with the solar transit into the Mesha (Aries) Rashi, lending it cultural and astrological importance.

The roots of Pana Sankranti can be traced back to ancient times, with references found in various scriptures and texts. The festival’s origins are deeply intertwined with the agrarian culture of the region. Marking the beginning of the new agricultural year, the festival highlights its importance in the traditional Odia way of life.

One of the most significant aspects of Pana Sankranti is its association with Lord Jagannath, the presiding deity of the Puri Jagannath Temple. According to legend, Lord Jagannath created the Pana drink to remedy the scorching summer heat. Another mythological tale associated with Pana Sankranti involves Lord Vishnu’s incarnation as Varaha (the boar). It is believed that on this day, Lord Vishnu rescued the Earth from the demon Hiranyaksha, an act of divine intervention that is commemorated through various rituals and prayers during the festival.

Pana Sankranti is celebrated with great enthusiasm and fervour across Odisha, with each region adding its unique cultural flavour to the festivities. At the festival’s heart is the preparation and sharing of Pana, a special drink that gives the festival its name. This refreshing concoction is made from many ingredients, including water, jaggery, fruits, and sometimes milk or yoghurt. The Pana is not only a delicious treat but also serves a symbolic purpose, representing the essence of life and the spirit of sharing. It is offered to deities and distributed among family members, friends, and neighbours, fostering a sense of community and togetherness.

Devotees mark Pana Sankranti by visiting temples dedicated to various deities, with special emphasis on Lord Jagannath, Lord Shiva, and Goddess Tarini. The Tarini Temple near Brahmapur and the Cuttack Chandi are particularly popular pilgrimage sites during this time. One of the most spectacular rituals associated with Pana Sankranti is the Jhaamu Yatra at Sarala Temple, where priests walk across hot coals, demonstrating their devotion and faith. This awe-inspiring display draws many spectators and adds to the festival’s mystical atmosphere.

Pana Sankranti is also a time for vibrant cultural expression. One of the most notable traditions is the Danda Nacha, or Danda Jatra, an ancient dance form dedicated to Goddess Kali. Performed by a group of men known as Danduas, this dance is a testament to physical endurance and spiritual devotion, often involving acrobatic feats and rhythmic movements. In different parts of Odisha, various cultural events mark the occasion. For instance, in Chhatrapada, Bhadrak, the Patua Yatra festival spans from April 14th to April 21st, bringing communities together. Northern Odisha resonates with the festivities of Chadak Parva, while in the south, the Meru Yatra festival marks the culmination of the month-long Danda Nata dance festival.

The festival is a time for strengthening social bonds. In urban areas, Odia families often gather in community halls to celebrate together, while in rural settings, the festival takes on a more traditional flavour with community-wide celebrations. These gatherings often feature feasts where traditional delicacies are shared, further reinforcing the sense of community and shared cultural heritage.

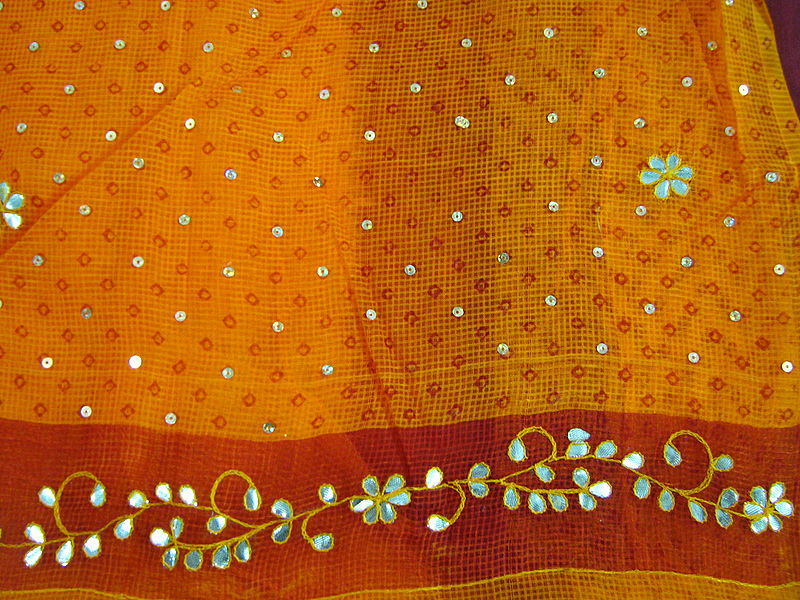

Pana Sankranti holds deep significance in Odia culture, embodying various symbolic meanings and cultural values. As the traditional New Year, Pana Sankranti symbolises new beginnings and fresh starts. It’s a time for people to clean their homes, wear new clothes, and set positive intentions for the year ahead. This reflects the universal desire for renewal and the opportunity to begin anew. Pana Sankranti marks the beginning of the new agricultural year. This connection to the land reminds people of the importance of agriculture in their lives and the need to maintain harmony with nature. The festival provides an opportunity for spiritual reflection and devotion. The various rituals, temple visits, and prayers associated with Pana Sankranti allow people to connect with their spiritual beliefs and seek divine blessings for the coming year.

Several myths and legends are associated with Pana Sankranti, adding depth and richness to the festival’s cultural significance. According to one legend, Pana Sankranti is linked to the story of Lord Vishnu’s incarnation as Lord Jagannath. It is believed that on this day, Lord Jagannath, with his siblings Lord Balabhadra and Devi Subhadra, embarked on their annual journey to the Gundicha Temple in Puri, known as the Ratha Yatra. The legend of Lord Jagannath creating the Pana drink as a remedy for the summer heat explains the origin of this central element of the festival and emphasises the belief in divine intervention in everyday life. The myth of Lord Vishnu, in his Varaha avatar, rescuing the Earth from the demon Hiranyaksha on this day adds a cosmic dimension to the festival. This story symbolises the triumph of good over evil and the restoration of cosmic order, themes that resonate with the idea of new beginnings associated with the New Year.

While Pana Sankranti is primarily celebrated in Odisha, similar festivals marking the solar New Year are observed across South and Southeast Asia. These include Vaisakhi in North and Central India and Nepal, Bohag Bihu in Assam, Pohela Boishakh in Bengal, and Puthandu in Tamil Nadu. Each of these festivals shares common themes of renewal and celebration while incorporating unique regional traditions and customs.

In Odisha, the celebration of Pana Sankranti can vary from region to region, with each area adding its local flavour to the festivities. In the Taratarini Temple area, the festival coincides with the Chaitra Yatra, drawing large crowds of devotees. In Northern Odisha, the Chadak Parva is a significant part of the Pana Sankranti celebrations. The Meru Yatra festival in Southern Odisha marks the end of the month-long Danda Nata dance festival, coinciding with Pana Sankranti. These regional variations highlight the diversity within Odisha’s cultural landscape and demonstrate how a single festival can take on different forms while maintaining its core significance.

As with many traditional festivals, the celebration of Pana Sankranti has evolved, adapting to changing social structures and urban lifestyles. In cities, community halls often become the focal point of celebrations, where Odia families gather to observe the festival. This adaptation allows urban dwellers to maintain cultural connections even in modern settings. The preparation and sharing of Pana remain central to the festival, but the recipe might vary from household to household, with some incorporating modern ingredients or adapting the drink to suit contemporary tastes. However, the spirit of sharing and community bonding remains intact.

Pana Sankranti plays a significant role in preserving and promoting Odia culture. The festival serves as a platform for showcasing traditional art forms, music, and dance, helping to pass these cultural treasures on to younger generations. The Danda Nacha, for instance, not only entertains but also educates people about ancient rituals and beliefs. Economically, the festival boosts local businesses. The demand for traditional foods, new clothes, and items used in rituals increased during this time, benefiting local traders and artisans. Additionally, the influx of visitors to temples and pilgrimage sites during Pana Sankranti contributes to the local tourism industry.

In recent years, there has been a growing awareness of the environmental impact of festivals. While Pana Sankranti is generally an eco-friendly celebration, with its focus on natural ingredients and traditional practices, efforts are being made to make it even more sustainable. For instance, some communities are promoting the use of biodegradable materials for decorations and encouraging the responsible disposal of waste generated during the festivities. The tradition of offering water to the Tulsi plant and the symbolic representation of rain through the Pana-filled earthen pot also serve as reminders of the importance of water conservation, especially relevant as the festival marks the beginning of summer.

Pana Sankranti stands as a testament to the rich cultural heritage of Odisha, blending spiritual devotion, communal harmony, and joyous celebration. This festival, with its deep-rooted traditions and evolving practices, continues to play a vital role in the cultural and social fabric of Odia society. As a celebration of new beginnings, Pana Sankranti offers a moment for reflection, renewal, and community bonding. It serves as a bridge between the past and the present, allowing people to honour their traditions while adapting to the changing world around them.

In an increasingly globalised world, festivals like Pana Sankranti play a crucial role in maintaining cultural distinctiveness while fostering a sense of unity and shared heritage. The enduring popularity and significance of Pana Sankranti demonstrate the power of cultural traditions to adapt and thrive, even in the face of rapid social change. As long as people continue to find meaning and joy in coming together to celebrate new beginnings, share in age-old customs, and reaffirm their cultural identity, Pana Sankranti will continue to be a vibrant and integral part of Odia life for generations to come.

/newsdrum-in/media/media_files/9UyYkq7ZBj0EYhd2ECGf.jpg)